Guaidó, Not Maduro, Is the De Jure President of Venezuela

The U.S., along with dozens of other states, recently recognized Juan Guaidó, the president of Venezuela’s National Assembly, as the legitimate president of Venezuela. Discussion of international recognition of Guaidó’s presidency has focused largely on the political implications of the move as a rejection of Nicolás Maduro’s corrupt dictatorship. While recognition typically focuses on a ruler’s de facto control over a territory, Guaidó’s de jure status under the Venezuelan Constitution is also crucial.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The U.S., along with dozens of other states, recently recognized Juan Guaidó, the president of Venezuela’s National Assembly, as the legitimate president of Venezuela. Discussion of international recognition of Guaidó’s presidency has focused largely on the political implications of the move as a rejection of Nicolás Maduro’s corrupt dictatorship. While recognition typically focuses on a ruler’s de facto control over a territory, Guaidó’s de jure status under the Venezuelan Constitution is also crucial. If Guaidó is clearly president under Venezuelan law, then recognition seems warranted here. Even setting aside the fact that Maduro’s kleptocratic rule has caused a humanitarian catastrophe, I believe that the best and most sensible reading of the Venezuelan Constitution leads to the conclusion that Juan Guaidó is now the interim president of Venezuela.

The fundamental principle of popular sovereignty—that governments must rest on the consent of the governed—has been at the foundation of Venezuelan democracy since 1958, when democratic forces deposed dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez. The country has undergone significant legal changes since then, but it has been governed by only two constitutions. The current one was adopted in 1999 after multiple popular referenda.

The present Venezuelan crisis began on Jan. 10, when Maduro was sworn in for a second term scheduled to end in 2025. Nobody seems to dispute that his first term ended that day, in accordance with Articles 230 and 231 of the Venezuelan Constitution. The relevant question is whether Maduro was in fact reelected and legally president after Jan. 10.

Any plausible reading of the constitution shows that Maduro was not reelected and, indeed, that there has been no election at all for the term beginning Jan. 10. Article 293 governs the process for calling and organizing new presidential elections, delegating to the National Electoral Council control over the process. Members of that body are nominated through a complicated scheme that gives significant power to the National Assembly, the country’s unicameral legislature, under Article 296. To Maduro’s chagrin, however, the National Assembly has been under opposition control since 2015.

In an attempt to circumvent the National Assembly, Maduro created a parallel legislature under Articles 347 and 348. These provisions, however, were meant solely to call for a constitutional convention and required a national referendum (like the one in 1999). Knowing that a popular vote would defeat his proposal, Maduro concocted an “electoral” process that would ensure every member of that alternate assembly would be under his control. That entire process was outside of the constitutional structure and violated the procedures prescribed by Article 347 and Venezuelan law. Under any sensible reading of the constitution, there was no basis for a parallel legislature nor the process by which it was staffed.

Here’s the key connection between that parallel body and the Venezuelan presidential elections: In 2018, the unconstitutional assembly called for, and organized, a presidential election—in direct violation of the constitution. The alternate assembly sidelined the actual National Assembly’s role, staffed the National Electoral Council with Maduro loyalists, and ensured another “election” that would keep Maduro in power.

All of that unconstitutional procedure means that the so-called presidential election of 2018 was de jure null and void. To make the election even more illegitimate, the process lacked even the most minimal guarantees of freedom or fairness required under the constitution and Venezuelan law. For example, the Maduro government:

- Banned opposition political parties, candidates, and leaders from running in the election.

- Illegally imprisoned opposition leaders before the election.

- Coerced and intimidated citizens into voting for the president’s party.

- Engaged in verifiable manipulation of vote tallies.

- Organized the process through an election authority controlled by members of Maduro’s party rather than those appointed by the National Assembly.

- Murdered protesters who exercised their right to assemble peaceably.

- Engaged in widespread and illegal use of government funds to finance Maduro’s campaign.

- Used state-owned media to promote Maduro’s candidacy.

- Disallowed international organizations from observing the vote.

Because of these violations, and others, there simply was no election under any reading of the Venezuelan Constitution. The National Assembly declared that the process did not constitute an election; the international community overwhelmingly rejected it as a sham; and opposition Venezuelan political parties boycotted the process. The U.N. human rights chief noted that the 2018 process did not “in any way fulfill minimal conditions for free and credible elections.”

The key to understanding Guaidó and the National Assembly’s argument is that, when Maduro’s presidential term concluded on Jan. 10, there was no elected president to assume the presidency. Maduro’s claims to the contrary are irrelevant, null and void.

In a situation with no president, Article 233 of the constitution regulates the presidential line of succession. In this case, that article is best read to mean that the president of the National Assembly should temporarily assume the presidency. To be sure, Article 233 does not explicitly contemplate a scenario in which there is no elected president. It does, however, envision a case in which the elected president is unable to assume the office on inauguration day due to death, resignation, disability, or “abandonment of his position, duly declared by the National Assembly,” among other reasons. The article then reads:

[W]hen an elected President becomes permanently unavailable to serve prior to his inauguration, a new election by universal suffrage and direct ballot shall be held within 30 consecutive days. Pending election and inauguration of the new President, the President of the National Assembly shall take charge of the Presidency of the Republic. (Emphasis added.)

The simplest and most straightforward reading of this provision is that in an analogous situation in which there is no president, the president of the National Assembly “shall take charge of the Presidency of the Republic.” Indeed, a situation entirely without an elected president necessitates this action by the National Assembly even more than one in which the president is permanently unavailable but potentially has a cabinet or other government officials in place. In such a situation, the National Assembly is the only properly constituted government branch, popularly elected body and sole representative of the people.

This reading is reinforced further by traditional rules of constitutional interpretation, which provide that in situations not foreseen by the constitution, provisions should be read in accord with the broader constitutional framework. Not only does a structural reading of Article 233 support this, but other constitutional provisions do too. Article 333 vests upon all citizens the duty to contribute to ensure the effectiveness of Venezuela’s constitution. Article 350, in line with the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, recognizes in individuals the right to resist any authority that undermines democracy and the effective exercise of human rights. Article 70 envisages open assemblies—which Guaidó has hosted—as a means through which citizens can exercise sovereignty.

Under the constitution, Guaidó is supposed to serve only on an interim basis for 30 days until new elections can be organized. However, Venezuelan lawyers disagree on the best reading of this provision. Some argue Guaidó can serve longer if the electoral process is scheduled within a reasonable time.

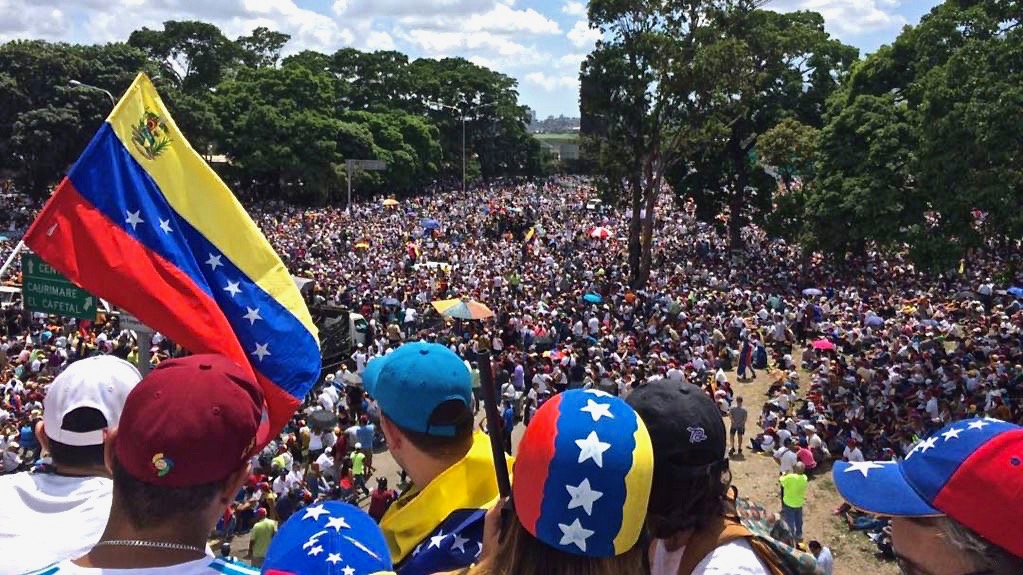

Taking all of this together, and in light of the vacancy of the presidency on Jan. 10, Juan Guaidó fulfilled his constitutional role as president of the National Assembly and assumed on an interim basis the presidency of Venezuela on Jan. 23.

This reading supports the Department of State’s position and reinforces the international community’s actions here: The Venezuelan Constitution places Guaidó as the de jure president. Although he is not in de facto control, international support may eventually turn the tide and reconcile this de jure-de facto divergence.

.png?sfvrsn=bd249d6d_5)