From Hollywood with Love: The Case of Colonel Abel

Who doesn’t love a Russian spy? Boris Badenov loved Natasha Fatale. James Bond loved KGB Maj. Anya Amasova. Joe Biden felt a certain something for Anna Chapman, the “deep-cover” Russian spy rounded up with nine others in June 2010. When Jay Leno asked the Vice President, “Do we have any spies that hot?” Biden lamented, “Let me be clear. It wasn't my idea to send her back.”

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Who doesn’t love a Russian spy? Boris Badenov loved Natasha Fatale. James Bond loved KGB Maj. Anya Amasova. Joe Biden felt a certain something for Anna Chapman, the “deep-cover” Russian spy rounded up with nine others in June 2010. When Jay Leno asked the Vice President, “Do we have any spies that hot?” Biden lamented, “Let me be clear. It wasn't my idea to send her back.”

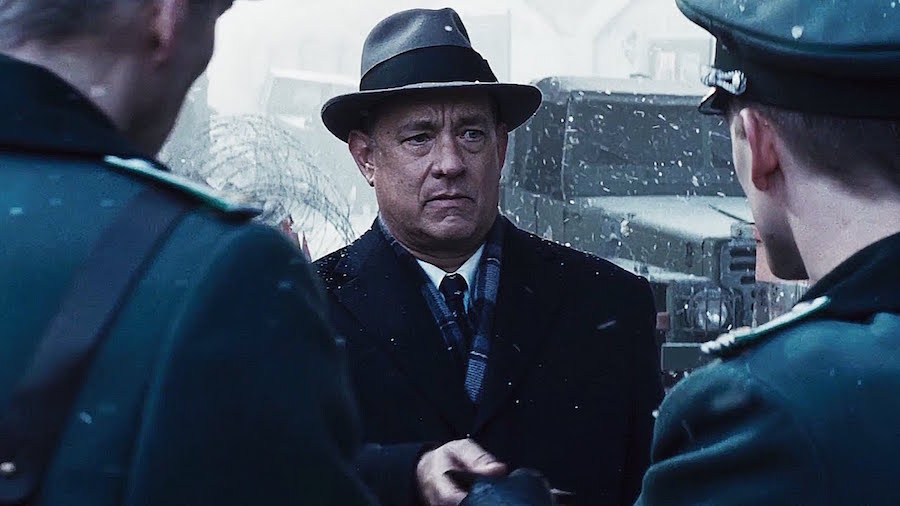

Steven Spielberg loves Russian spies, too (although this time, Hollywood did not produce a Bond girl). His latest film, opening today, is Bridge of Spies. Tom Hanks plays Jim Donovan (a former advisor to, but no relation of, “Wild Bill” Donovan). He is the pro bono lawyer for KGB Col. Rudolf Abel (played by Mark Rylance). No doubt the Coen brothers’ script will entertain audiences. But it probably won’t focus on the actual law behind Abel’s arrest, detention, trial, and two trips to the U.S. Supreme Court.

For those who want more law with their Hollywood, I wrote an article when Chapman got rolled: The Case of Colonel Abel. Bloomberg Radio’s June Grasso and Michael Best interviewed me Monday about Spielberg’s movie and my article, with a 17-minute podcast available here and a 3-minute version here. The Brooklyn Historical Society will host a panel discussion next month, at which I’ll join some of Abel’s biographers and a documentary film-maker to discuss the case.

Abel’s “famous capture” was the metric journalists used to measure the significance of Chapman’s arrest almost exactly fifty-three years later. Abel was caught in flagrante delicto, half-naked, in a Manhattan hotel room surrounded by the tools of his trade, including a cipher pad, hollowed-out pencil, and microfilm. A hollow nickel and encrypted messages were discovered elsewhere.

The goal was to quietly turn Abel into a double agent. So no warrant was sought for Abel’s arrest, which the FBI accomplished using the INS as its cat’s paw. Justice Brennan, dissenting from the 5-4 opinion in Abel v. United States, described what happened next: “[Abel] was taken to a local administrative headquarters and then flown in a special aircraft to a special detention camp over 1,000 miles away. He was incarcerated in solitary confinement there. As far as the world knew, he had vanished.”

Abel didn’t break, which led to his indictment for atomic espionage after weeks of conveyor belt interrogation in southernmost Texas. Donovan lost the case but saved Abel from execution, arguing that someday he could be traded for a captured American spy. As it turns out, that was Francis Gary Powers, whose U-2 spy plane was shot down over the Soviet Union. The trade was on the Glienicke Bridge -- the “bridge of spies” -- a border crossing between East Germany and West Berlin.

My article dives deep into this legal history, drawing on briefs and trial transcripts, Donovan’s diary, and a series of interviews with a key member of the prosecution team, Anthony R. Palermo (like Donovan, an extraordinary lawyer). I also explore some parallels between Donovan’s time and ours, including the public pummeling Donovan took for his pro bono defense of Abel (not unlike crude attacks on the Guantánamo defense bar) and the pretextual use of legal authority (the unresolved issue behind Ashcroft v. al-Kidd).

Colonel Abel’s case still fascinates. Both sides presented arguments that resonate in our time, which perhaps led Spielberg to make his film. To the jury that decided Abel’s fate, the prosecutor gave this reminder in closing argument: Colonel Abel’s actions were “directed at our very institutions and through us at the free world and civilization itself.” Donovan’s essential response was that our legal institutions shouldn’t be weakened in that fight, based “on a false premise which may be mumbled, ‘an arrest is an arrest is an arrest.’”

I’m sure the movie will be great, classic Spielberg. But the real Abel case should leave you … wait for it … shaken, not stirred.

_-_flickr_-_the_central_intelligence_agency_(2).jpeg?sfvrsn=c1fa09a8_5)