In the House Strzok Hearing, a Reminder of Congress’s Shortcomings on Oversight

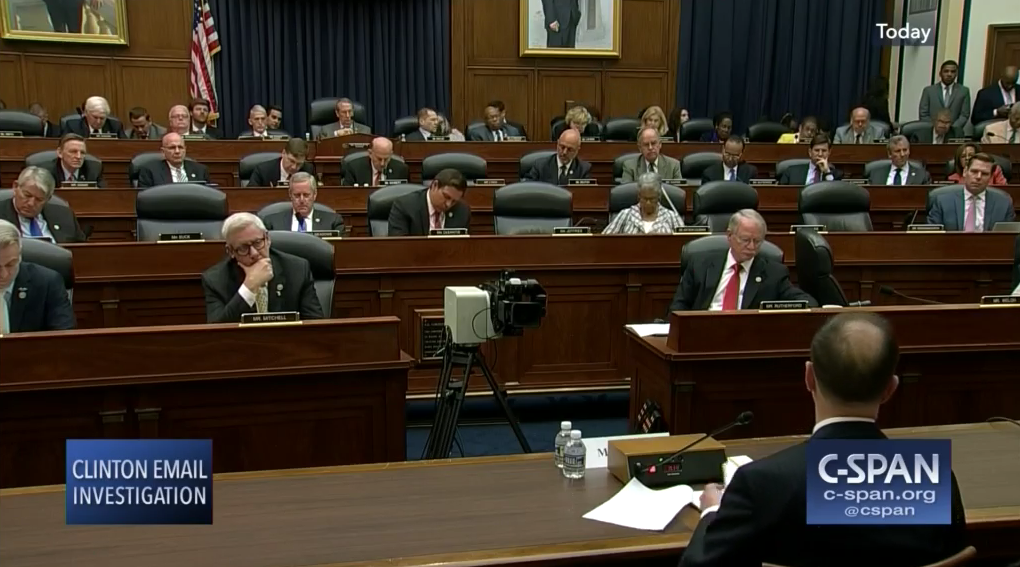

The House of Representatives hearing Thursday with FBI agent Peter Strzok was far from the chamber’s finest 10 hours. The shortcomings, however, go beyond the House’s role in partisan political fighting over the FBI and its investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 elections. Nor are the shortcomings limited to the splashiest moments of the hearing, such as when Rep. Louie Gohmert (R-Tex.) invoked Strzok’s marriage.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The House of Representatives hearing Thursday with FBI agent Peter Strzok was far from the chamber’s finest 10 hours. The shortcomings, however, go beyond the House’s role in partisan political fighting over the FBI and its investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 elections. Nor are the shortcomings limited to the splashiest moments of the hearing, such as when Rep. Louie Gohmert (R-Tex.) invoked Strzok’s marriage. Rather, from an institutional perspective, the session underscored how deeply Congress’s oversight muscles have atrophied and how much work must be done to reinvigorate them.

To be clear, the decline of meaningful congressional oversight isn’t new; my Brookings colleague Tom Mann and his co-author Norm Ornstein, for example, were writing about it more than a decade ago. Chaos at hearings isn’t novel either. But one episode from the Strzok session is particularly illustrative (scroll down to watch it).

A little more than an hour into the hearing, after a forceful response from Strzok to a line of questioning from Rep. Trey Gowdy (R-S.C.), Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-Calif.), citing House Rule XI, Clause 2, moved to issue a subpoena to former Trump adviser Steve Bannon to compel his appearance before the Judiciary Committee. The committee chairman, Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.), after consulting with staff, ruled the motion “not germane.” Swalwell, wanting to object, initially made the wrong motion (a motion to table) before a colleague pointed him to the correct one (an appeal of the ruling of the chair). Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.) then moved to table, or kill, Swalwell’s appeal and, with it, the underlying attempt to subpoena Bannon.

Up to this point, the procedural back-and-forth is relatively typical. As I have argued elsewhere, service in Congress can be like a giant game of whack-a-mole, especially for members of the minority party (as Swalwell is). Members have political and policy goals they want to achieve, and when various avenues for achieving those ends get cut off—like moles being whacked down—whatever means are left standing bear the burden of everything legislators want to get done. Swalwell wanted to force his Republican colleagues to vote on a Bannon subpoena, and Sensenbrenner’s move—to table Swalwell’s appeal—is a usual majority-party response to an unwanted move by their minority-party colleagues.

But there is more to this exchange. Goodlatte’s initial hesitation about how to handle Swalwell’s motion, and Swalwell’s corresponding uncertainty about the appropriate response, as well as what came next, are indicators of the challenges Congress faces in conducting meaningful oversight. Once a roll-call vote on Sensenbrenner’s motion to table was requested, the Judiciary Committee’s top Democrat, Rep. Jerrold Nadler (N.Y.), requested clarification on how voting would proceed because the hearing involved the members of both the House Judiciary Committee and the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform (in total, 85 members). Goodlatte said his understanding was that both Nadler and the Oversight Committee’s top Democrat, Rep. Elijah Cummings of Maryland, “were satisfied with one roll call vote” of the combined committees. The question would be decided on the combined votes of both panels, but the vote would be conducted by having first the Judiciary clerk and then the Oversight clerk call the roll of their respective panels. After an initial roll call, Goodlatte had to remind members that if they were on both committees, their votes would be counted only once, not twice. Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) inquired about the arrangement—essentially asking whether he, as a member of both panels, could cast two votes. Goodlatte explained that no, just one unified vote would be taken. The motion to table carried, Swalwell’s subpoena was quashed, and the hearing continued.

Given that hearings involving multiple committees are relatively rare, this confusion might appear understandable or, at least, forgivable. But the rules and procedures by which oversight hearings are conducted aren’t merely weapons the two parties can use to try to gain leverage over one another. Knowing how they work and allowing them to dictate the conduct of the hearing are vital to successful, productive hearings that elicit meaningful information from the witnesses. Understanding the procedures at hand is necessary for effective oversight—but by no means sufficient. And while the underlying purpose of Thursday’s hearing was principally political, rather than substantive, this display of confusion does not bode well for the return of successful oversight in the future.

-final.png?sfvrsn=b70826ae_3)