How Politics at Home Shapes Kuwait’s Foreign Policy

What does the succession of Kuwait's new emir signal for the Gulf state's foreign policy?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

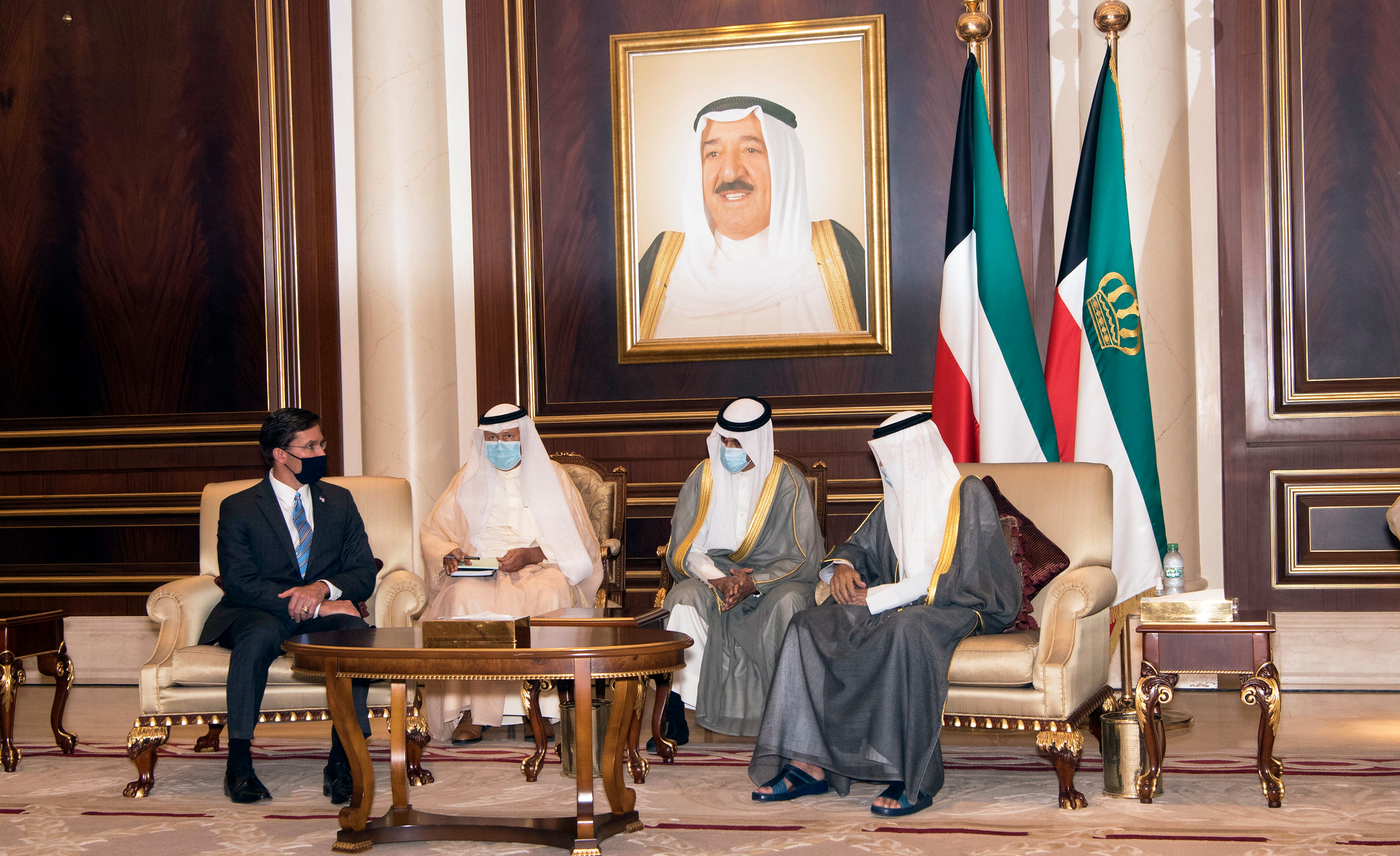

Editor’s Note: In a region known for new leaders reshaping the policies of their predecessors, the death of Kuwaiti emir Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah raises questions about whether Kuwait, like the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, will go in new directions under its new leadership. Courtney Freer, my Brookings colleague as well as a professor at the London School of Economics, argues that Kuwait’s foreign policies are likely to show more continuity than change, in large part because they are anchored in the country’s domestic politics.

Daniel Byman

***

The passing of Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah, the emir of Kuwait, in September has raised questions about whether Kuwait will continue its independent foreign policy. As Kuwait’s foreign minister for four decades (1963-2003) and emir for nearly 20 years (2006-2020), Sheikh Sabah shaped Kuwait’s role in the Middle East as an active mediator and humanitarian partner. In particular, when it comes to the ongoing rift that has divided Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) from Qatar since 2017, Kuwait under Sheikh Sabah remained neutral and led conciliation efforts; under his leadership, Kuwait also hosted a large donor conference in February 2018 at which some $30 billion was pledged to help Kuwait’s former enemy Iraq, illustrating the country’s commitment to leading aid engagement in the Gulf. Kuwait has also, more recently, demonstrated its continued loyalty to the Palestinian cause despite Bahrain’s and the UAE’s normalization of ties with Israel.

Will the new emir, Sheikh Nawaf al-Ahmad al-Sabah, continue Kuwait’s independent foreign policy? So far, the tea leaves favor stability: Sheikh Nawaf, shortly after his ascension to the throne, requested that the existing cabinet remain in place until after the parliamentary election is held on Dec. 5, signaling a desire for continuity during the transition period and beyond. A consistent foreign policy is likely because Kuwait’s domestic and foreign policies are linked.

Kuwait’s pluralistic domestic political environment—protected by its 1962 constitution that grants parliament the power to question ministers, and propose and block legislation—has helped sustain its pluralistic foreign policy stance. Kuwait, unlike its neighbors Saudi Arabia and the UAE, has not designated the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organization, largely because the Brotherhood has been a part of the Kuwaiti political environment since the 1950s. And although the Kuwaiti Muslim Brotherhood has at times been part of a broad-based political opposition, it has never been considered fundamentally threatening to the Kuwaiti system or government. Further, Kuwait has not demonized Iran to the same extent as neighboring Saudi Arabia; it houses a politically active, though not oppositional, Shiite minority that has participated in parliament for decades and forms an important part of the country’s merchant community. In fact, between the years of 2012 and 2016, during an opposition boycott, Shiite Islamist blocs, which in recent years are largely loyalist, represented the largest contingent in parliament. Given their prominence in bolstering the political status quo, the monarchy cannot isolate Kuwait’s Shiites as a fifth column in the way that Saudi Arabia has done—it would be nonsensical and unproductive.

Despite the general political openness in Kuwait, redlines do exist. Insulting the emir is a criminal offense, which has resulted in long prison sentences for members of the opposition. The emir also has the authority to dissolve the legislature and, although the constitution requires that it be voted back in within two months, Kuwait has witnessed two long periods without parliamentary life: 1976-1981 and 1986-1992. The implementation of a new electoral law in 2012, which granted each Kuwaiti citizen one rather than four votes, spurred protest and a four-year election boycott by the opposition because it was seen as a means of limiting the representation of the organized political blocs that form the backbone of the opposition.

The Broader Gulf Cooperation Council

Foreign policies toward Islamists across the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) appear to have clear domestic corollaries: Where the Muslim Brotherhood or Shiite Islamist groups are considered oppositional or in some way threatening to the government’s legitimacy, they are repressed. It is no coincidence that Saudi Arabia and the UAE have chosen to isolate both groups, having designated the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist movement in 2014. And although the UAE does not have a sizable politically active Shiite population, Saudi Arabia has effectively securitized its Shiite population, having cracked down on Shiite strongholds in the Eastern Province as a means of isolating that population and dubbing it a terrorist threat to ensure its inability to become politically influential.

Although Sean Yom has argued that Kuwait’s domestic pluralism has restricted the nation’s foreign policy due to parliament’s involvement in certain foreign policy decisions, I argue that the opposite is true, at least when it comes to the treatment of Islamist movements. Because Sunni and Shiite Islamists form part of the domestic political system and are seen as components of political life rather than competitors, Kuwait has had greater space for foreign policy creativity and multilateralism. This is also true in Qatar, where the local Muslim Brotherhood branch chose to dissolve itself in 1999 and Sunni Islamist movements are now seen as potential partners rather than political opponents. This attitude was reflected most clearly in Qatar’s foreign policies during the Arab Spring, and particularly its support of the elected Mohammed Morsi government in Egypt in 2013 and 2014. Further, Qatar has a very small Shiite minority and no Shiite Islamist political blocs, meaning that this segment of the population is similarly not seen as a political threat, making relations with Iran less problematic domestically.

Meanwhile, in the Kuwaiti domestic political sphere, no actor is working to ban or restrict either the Muslim Brotherhood or Shiite Islamist movements; similarly, there is no serious consideration of joining the blockade against Qatar, which is seen as a GCC champion of Sunni political Islam, or completely halting ties with Iran. Because of the prevalence of Islamist movements in Kuwait and the space provided for them within government institutions, their domestic voice is important in foreign policy. This is perhaps best illustrated by Kuwait’s stance against normalization with Israel, an issue about which Kuwait’s Islamists have been particularly vocal and that 37 of 50 members of parliament recently publicly opposed. The Kuwaiti government has insisted that it will be “last to normalize” ties with Israel, illustrating the extent to which foreign policy is linked to domestic politics and popular opinion.

Moving Forward

Kuwait is unique among its neighbors in the Arabian Peninsula in that it houses a politically active parliament that includes a range of actors, various Shiite and Sunni Islamist blocs among them. And while Kuwaiti foreign policy has arguably been based on Sheikh Sabah’s vision of the role of Kuwait in the Middle East, its foreign policy has now become linked to Kuwait itself. Notably, Kuwaiti foreign policy is not formed solely at the top, as it is elsewhere in the GCC; public opinion and domestic politics matter, as Yom has pointed out. Political pluralism at home has allowed for an independent foreign policy and multilateralism abroad.

The Saudi and Emirati leaderships, meanwhile, remain focused on containing regional forces that they see as existential threats to their hold on power. They do so at home through the repression of both Shiite and Sunni Islamists and abroad by supporting leaders in Egypt, Libya, Sudan and Yemen who arguably share the same threat perceptions. In a sense, as May Darwich has noted, authoritarianism when it comes to Islamist movements has become truly transnational, since many governments in the region see domestic gains as linked to a broader regional strategy to maintain and expand their power.

The Kuwaiti foreign policy vision, however, which advocates for inclusion of Islamists over repression, reflects notions of the importance of political competition at home and therefore is unlikely to change even under new leadership.

Kuwait’s relationship with the United States is likely to remain stable and could potentially become stronger without pressure from the Trump administration to normalize relations with Israel. With President-elect Joe Biden having said in the past that he intends to isolate Saudi Arabia as a “pariah,” changes in U.S. foreign policy in the Gulf could alter Kuwait’s relationship with Saudi Arabia and make Kuwait, rather than Saudi Arabia or the UAE, a preferred partner for U.S. interests in the region precisely because of its moderate and multilateral foreign policy.