How Tech Regulation Can Leverage Product Experimentation Results

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

In recent months, prompted by concerns over social media platforms and the public deployment of consumer AI chatbots, new urgency has been added to calls for technology regulation. A range of new state laws have been passed (including notable ones in California and Utah); multiple proposals in Congress have been introduced, including new energy from the Senate majority leader; and the Supreme Court—despite sidestepping substantive engagement during Gonzalez v. Google—will again likely take up a review of platform protections under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act next year.

Yet both the public and each of these governmental processes is missing critical data for adjudicating these issues: the experimentation results that companies themselves use to make product decisions. Experimentation results, and the methods companies use to deploy them, offer direct insight into the causal effects of product design choices that companies make and how they make trade-offs. Oversight could begin with transparency into these questions, using that information to inform how and when to regulate decisions that are leading to societal harm. More specifically, for questions that have burst into the public debate—like whether kids’ mental health is really being hurt by exposure to social media, or whether product choices lead to more threats of violence and harassment including of elected officials—these results could help separate correlation from causation, while helping regulators understand platform dynamics in the same way that companies themselves evaluate and respond to such questions.

We have been involved in hundreds of product experiments and have seen up close how platforms rely on experimentation results to drive decisions. Algorithms often receive hundreds of inputs, many of which are derived from other complex systems. Platforms have admitted that their systems are not well understood internally, and many of the downstream effects of any particular change cannot be anticipated, a reality only exacerbated by the increasing use of black-box AI systems. Instead, product teams make choices by measuring the experimental effects of product changes on a range of metrics. At times, these choices weigh benefits for users (e.g., reduced bullying and misinformation) against costs to company business metrics (e.g., users “logging onto the platform .18% less”).

Outside of a few leaks and self-selected disclosures, the public has very limited line of sight into these processes. But even those limited samples have proved illustrative.

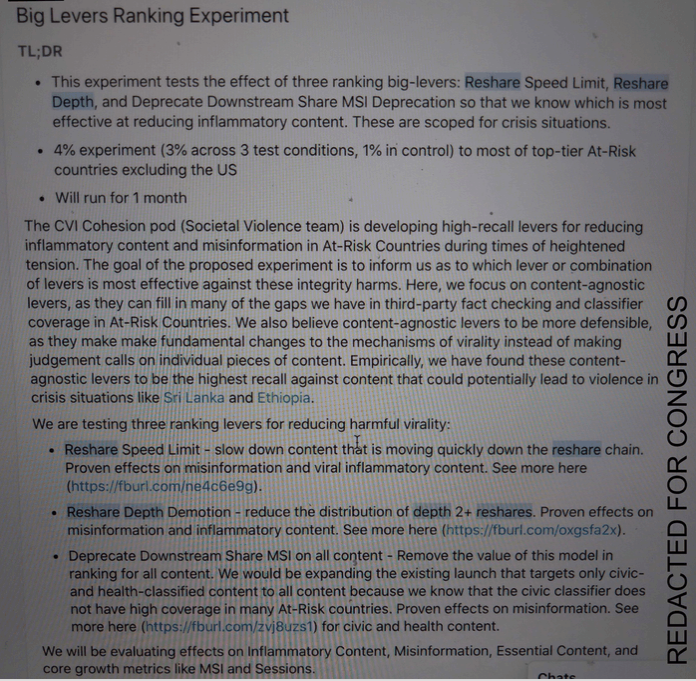

Consider one example that engages directly with one of the strongest criticisms of technology platforms: that they induce violence in countries like Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Ethiopia. As revealed in Gizmodo’s Facebook file repository, in 2021 three interventions were tested against each other to assess the spread of inflammatory content in such contexts. Each experimental change reduced the influence of “reshared” content in a specific way, and each intervention was noted to already have “proven effects on misinformation.” A separate document shows that one of these interventions, “replacing downstream value,” reduced misinformation for health and civic content by 7-12%.

Screenshot of “Big Levers Ranking Experiment” document from Gizmodo’s Facebook Paper Archive.

The overall results of this experiment are not public, but the documentation suggests that the team responsible for the test planned to “evaluat[e] effects on inflammatory content, misinformation, essential content, and core growth metrics like MSI and Sessions.” MSI refers to “meaningful social interactions,” a critical internal growth metric at Facebook, and reporting shows that the company eventually decided to reduce the weight of reshared content in the MSI metric and removed it entirely for political content—which measurably reduced bullying, misinformation, graphic content, and anger reactions. These examples offer direct experimental evidence that a single feature (reshare optimization) on a single platform can lead to critical downstream effects on public discourse and negative user experiences.

This example reflects the way technology companies typically evaluate changes to their products. Several metrics are consistently measured and evaluated in almost all product modifications; here, that includes MSI and related growth metrics that filter up to overall platform goals and impact revenue. The data involved in this example is representative of how experiments are typically run. The “current” version of the product is treated as the base scenario, with users randomly assigned to a group that experiences the unmodified product or to a group that experiences the product with one or more modifications. By examining the changes between these groups (e.g., Did one group engage less, leading to reductions in MSI? Did one group report less bullying content? Did one group see less known misinformation?), companies can estimate the causal impact of making a product change, even within a complex system where the mechanism for this impact may be less well understood.

Because experiments are happening all the time across teams and groups, there is a good chance that most individuals who have used the platforms for a significant length of time have been in one of these experiments even if they did not know it. These simple dashboard summaries are reflective of a data-driven culture interested in optimization but not constrained outside of direct business interests. The ubiquity of these tests means that they can provide a rich source of data for external audiences to understand what any given product choice may cause, at least for the measured metrics.

Experimentation is used widely by scientists to disentangle issues of causality from correlation. Platforms insist that they are not a primary cause of institutional decline, but rather reflect existing societal trends, while critics insist that the platforms’ products are causing a decline in democracy. Scholars often conduct experimental studies on platforms as a whole because feature-level studies are difficult to coordinate, slow to report, and capture changes for only a single version of a product. The public debate would be much richer with similar experimental results for meaningful product changes, such as optimization for viral reshared content. Such data could illuminate the specific causal impact of individual product choices.

Technology transparency is a goal that already unites disparate political groups, with a variety of proposed laws including the bipartisan Platform Accountability and Transparency Act (PATA), which would grant access to platform data for accredited independent researchers via the National Science Foundation. These are worthy efforts, yet none of these proposals focuses on the experimental results from the countless A/B tests that platforms run.

What would it take to implement transparency of the format we’re proposing? It would require a few components, many that could build on the foundations provided by proposals like PATA in the U.S. or the Digital Services Act in the EU. Specifically, for large platforms covered by these provisions (size and qualification rules are provided for in those proposals), platforms would need to:

- Document and maintain records for product experiments, including which product changes were being tested and which metrics were or were not affected. Where existing practices are robust (like the Facebook example above), platforms could simply provide access to existing data. Metrics of particular interest to society (e.g., hate speech, misinformation, bullying) could be mandated for inclusion in these records.

Document how these experimental results relate to decisions that were made, team goals, and overall company goals, often expressed with objectives and key results (OKRs).

Provide regular access to this data to a preapproved group of third-party reviewers scoped under the regulation, such as the researchers identified under the PATA provisions, or by internal regulators at a federal agency.

In coordination with reviewers, publish the results of these experiments on an appropriate timeline. Publication is critical if the wider scientific community, including those in non-Western institutions, hopes to develop a cumulative science of how product decisions affect society.

One criticism of transparency requirements, especially for third-party reviewers, is that they put the privacy of users at risk. This concern is a legitimate one, albeit one that can be addressed via the protections afforded in a proposal like PATA. In this case, though, these concerns are much less acute: Experimental results of the sort illustrated in the prior example may deal with sensitive information and speak to direct business interests—but they do not generally reveal data about any specific user. The purpose of experiments is to evaluate treatment effects on aggregate populations, and outside of descriptive statistics of demographics, no personal identifiable information need be revealed, except in limited auditing functions.

At the same time, private enterprises, including social media platforms, have a legitimate need to protect their capacity for innovation. Providing visibility into A/B test results does not need to be implemented in a way that would limit innovation.

First, laws could limit the scope of reported results to metrics of particular societal interest (e.g., relating to mental health), similar to Environmental Protection Agency regulations that protect public health or Federal Trade Commission fraud protections. Second, our suggested implementation limits immediate visibility to those who have a legitimate need, such as regulators and academics. PATA offers one way that such a process could be adjudicated. Third, published results can be released over a period of time, such that the results are outdated for competitors seeking insight into product development, even as regulators seeking to reduce risk might examine test results for particularly risky changes sooner. Similar transparency laws have been designed before, such as a law from 2020 designed to reduce forced labor and human trafficking via transparency into business supply chains.

Many platform employees would like to productively contribute to public knowledge about product decisions. While no system can eliminate risk, standardized processes for evaluating product changes for societal harms can move some of that risk and responsibility from companies to regulators, whose job it is to be more publicly accountable. Such processes can also contribute to societal knowledge about how best to build these systems, which is knowledge that is currently often limited to employees of technology companies.

The proliferation of recent legal action and state lawmaking is indicative of a bipartisan desire to hold technology platforms accountable. Having access to the experimental results that platforms themselves use to understand their products is a simple, powerful step toward effective transparency. As AI-powered systems gain more prominence in daily life, the desire to meaningfully participate in technology design decisions will only become more important.

Editor’s note: Meta provides support for Lawfare’s Digital Social Contract paper series. This piece is not part of that series, and Meta does not have any editorial role in Lawfare.

.png?sfvrsn=4156d4f8_5)

-(1)-(1).png?sfvrsn=1bc11cd_4)