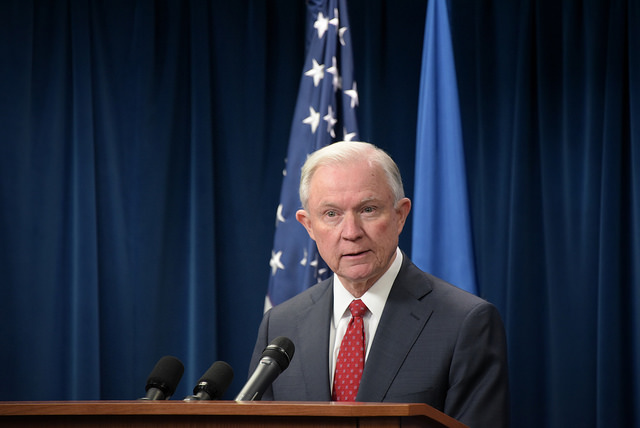

If the Attorney General Is Fired, Who Acts as Attorney General?

Although Attorney General Jeff Sessions has reportedly expressed no inclination to resign, President Donald Trump’s evident and quite public “disappointment” over Sessions’s (clearly correct) decision to recuse himself from investigations relating to the 2016 presidential campaign raises the prospect of a potential vacancy in the office of the attorney gen

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Although Attorney General Jeff Sessions has reportedly expressed no inclination to resign, President Donald Trump’s evident and quite public “disappointment” over Sessions’s (clearly correct) decision to recuse himself from investigations relating to the 2016 presidential campaign raises the prospect of a potential vacancy in the office of the attorney general. Such a vacancy would render arcane Department of Justice succession rules tremendously consequential, as the person who would act to fill that vacancy could assume the mantle of supervising Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation until a new attorney general is confirmed.

How much discretion does the president have to choose who would act as attorney general? The answer turns on whether the deputy attorney general and associate attorney general have priority under a specific statute governing DOJ succession (28 U.S.C. § 508) before the president can turn to the Vacancies Reform Act. If, as some have suggested, the president can make a designation under the VRA even when there is a confirmed deputy and associate, the president would have broad latitude to select from a wide range of officials to serve temporarily as his acting attorney general. But the question of whether the president can use the VRA not just to supplement the succession order provided by section 508 but to supplant it altogether is unresolved and raises complicated questions. To understand why, some background on ordinary DOJ succession rules is necessary.

Under Regular Order

In ordinary times, the question of Attorney General succession is straightforward. Section 508 directly addresses DOJ succession and provides that “[i]n case of a vacancy in the office of Attorney General, . . . , the Deputy Attorney General may exercise all the duties of that office.” Consequently, if Sessions is fired or resigns, under this provision Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein would assume the attorney general’s authorities.

The statute further provides that if both the attorney general and the deputy attorney general are unavailable or unable to serve, the associate attorney general “shall act” as attorney general. Thus if Rosenstein is unavailable to act—whether as a result of a recusal, resignation, or termination—under this provision Associate Attorney General Rachel Brand would act as attorney general.

The statute also authorizes the attorney general to “designate” the solicitor general and the various assistant attorneys general in “further order of succession.” Assuming this attorney general order has not been revised since 2007, it designates the solicitor general and then the assistant attorneys general for the Office of Legal Counsel, for National Security, for the Criminal Division, for the Civil Division, and then other litigating divisions to serve as acting attorney general in that order. For present purposes, however, these positions are themselves currently vacant. This could change as the Senate confirmation process moves forward. Several nominees—including the nominees to serve as solicitor general, assistant attorney general for the Office of Legal Counsel, and assistant attorney general for the Antitrust Division—have been voted out of the Senate Judiciary Committee and are currently awaiting floor votes on confirmation.

Ordinarily the president’s authority to fill vacancies temporarily under the VRA would supplement the line of succession at this point. And in March 2017, President Trump issued an executive order specifying three additional officials to serve as acting attorney general in the event that the DOJ succession order is exhausted: the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, currently Dana J. Boente; the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of North Carolina, currently John Stuart Bruce; and the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Texas, currently John R. Parker. The executive order excludes acting officials, but all three current officials are eligible; Boente is Senate-confirmed and Bruce and Parker are serving as interim U.S. Attorney by court appointment under another statute governing U.S. Attorney vacancies. Importantly, the president can change (at least) this portion of DOJ’s succession order at any time by simply making new designations.

In sum, under ordinary succession rules, Rosenstein, Brand, Boente, Bruce, and Parker would currently be next in line to serve as acting attorney general, at which point a new presidential designation would be necessary. Additional officials might be confirmed and become automatically slotted into this succession order, and the president is free to modify at least the latter part of this list. But the key question is whether the president is free to disregard this succession list altogether.

Can the President Designate an Acting Attorney General Under the Vacancies Reform Act?

The VRA provides a general rule addressing vacancies in Senate-confirmed positions across (most of) the executive branch. Under the VRA, the “first assistant” generally assumes the acting position unless the president designates another person holding a Senate-confirmed office or a senior official at the agency where the vacancy arises who has been at the agency for at least 90 of the past 365 days. An acting official designated under the VRA can serve for 210 days (or more, in certain circumstances).

How do these general authorities apply when there is also a specific statute addressing succession for the position where a vacancy arises? The VRA says that it is the “exclusive means” for filling vacancies in Senate-confirmed positions unless another statute expressly “designates” an officer or employee to perform the functions of the office in an acting capacity or “authorizes” the president, the head of the agency, or a court to make such a designation. Section 508 does both, so the VRA is not the “exclusive means” to designate an acting attorney general.

But is the VRA an alternative mechanism that can be used at any time, rather than simply providing authority to supplement the succession order established by section 508? If so, the president could go around Rosenstein and Brand and select from a wide range of officials to temporarily serve as his acting attorney general, including senior political appointees at DOJ who have served more than 90 days since the inauguration, numerous career DOJ officials, and lawyers serving in Senate-confirmed positions in other agencies. And the list of potential candidates continues to grow as additional U.S. attorneys or other lawyers are confirmed by the Senate to executive branch positions.

Whether the president can designate someone under the VRA to serve as acting attorney general in place of a confirmed deputy or associate attorney general is unresolved. After Attorney General Alberto Gonzales resigned, a 2007 Office of Legal Counsel opinion held that the president could designate the assistant attorney general for the Civil Division to serve as acting attorney general under the VRA notwithstanding the fact that a Senate-confirmed solicitor general was available to serve pursuant to the attorney general’s designation under section 508. But the positions of deputy attorney general and associate attorney general were vacant at the time, and the opinion rests in part on the view that it would be odd for the attorney general’s designation to take precedence over the president’s designation.

The same reasoning would not apply to the deputy and associate attorneys general, who are expressly specified in section 508 by Congress (rather than by attorney general designation) to serve as acting attorney general in the event of a vacancy. The tenor of section 508—which directly imbues the deputy attorney general with the authorities of the attorney general in the event of a vacancy, and further provides that the associate attorney general “shall” serve as acting attorney general if both the attorney general and the deputy are unavailable—suggests that Congress intended their respective places in the succession order to be mandatory. As a matter of statutory interpretation, this sort of specific direction generally takes precedence over more general provisions. Indeed, section 508 would arguably give the deputy attorney general the authority to “exercise all of the duties” of the attorney general even if another official was designated to act under the VRA, an anomalous result that would leave two officials with potentially conflicting authority. So OLC (or, if there is ensuing litigation, the courts) might conclude that the VRA provides an alternative mechanism to section 508 only when the offices of the deputy and associate attorneys general are vacant. (Reading the statute this way, though, requires concluding that section 508’s clarification that the deputy attorney general “is the first assistant to the Attorney General” for purposes of the VRA does not incorporate the VRA in full.)

In the event that Sessions is fired, there is a second question regarding the president’s authority to fill the resulting vacancy through the VRA. As Stephen Vladeck points out, it is not clear that the VRA “applies when the previous officeholder is fired (the statute is triggered when the current officeholder ‘dies, resigns, or is otherwise unable to perform the functions and duties of the office’),” and the moral hazard created by allowing the president wide discretion to make an unreviewable temporary appointment to act in place of a Senate-confirmed official he fired is one good reason why this omission might have been intentional on Congress’s part. On the other hand, for most positions there is no mechanism to fill a vacancy temporarily other than the VRA, and it would be odd if there were no mechanism whatsoever to fill vacancies that result from a termination pending confirmation of a replacement.