Imagining a Senate Trial: Reading the Senate Rules of Impeachment Litigation

The rules under which Donald Trump will face trial in the Senate are a combination of theatrically detailed and maddeningly vague.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

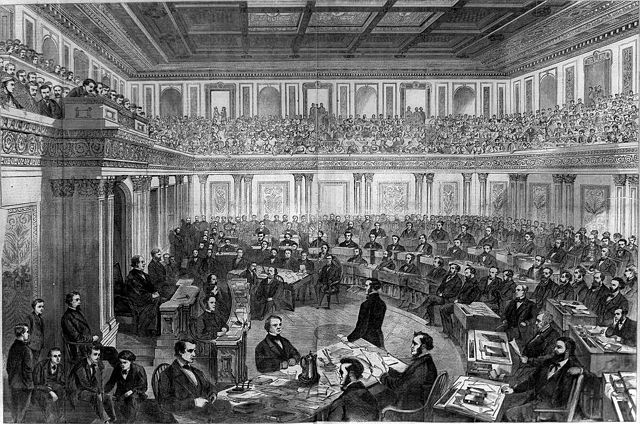

On some unspecified day in the future, probably but not certainly in January, a group of gray and black suits will march into the Senate chamber in the Capitol building. After months of public debate, the release of the Mueller report, and witness testimony both in private depositions and in public hearings, the House Judiciary Committee will have by then passed articles of impeachment against President Trump, and the full House of Representatives will have passed them as well. The suits entering the Senate will be the House’s so-called impeachment managers, those members named by the body to prosecute the House’s case in the Senate trial of the president.

They will enter the Senate chamber under a series of theatrical stage directions, which are laid out in a document entitled, “Rules of Procedure and Practice in the Senate when Sitting on Impeachment Trials.” The Senate’s impeachment rules are weirdly detailed, specifying speeches and oaths that different actors must recite and the specific times of day when things must happen. Yet they offer no rules of evidence or standards of proof and allow majority votes in the Senate to decide key questions that in any normal trial proceeding would be decided by judges under law.

Following these rules, the managers—led, say, by Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff—will have alerted the Senate that they’re ready to present the articles, and Julie Adams, the secretary of the Senate, will have responded that the Senate will receive them. Schiff and the others will approach the Senate bar. The Senate’s sergeant at arms, Michael C. Stenger, will proclaim: “All persons are commanded to keep silence, on pain of imprisonment, while the House of Representatives is exhibiting to the Senate of the United States articles of impeachment against Donald Trump.” Following Stenger’s proclamation, the House managers will exhibit the articles, displaying their allegations against the president.

A few blocks away, Chief Justice John Roberts will have already received a request from the Senate—the first time in more than 20 years a chief justice will have received such a summons: He must arrive at the Capitol building the next day at 1:00 p.m. to preside over the consideration of the impeachment articles. The chief justice will return to the Senate daily—except on Sundays—while the articles are being considered and throughout Trump’s trial. No one is certain how long that may take.

The following day, the chief justice will arrive at the Capitol and take an oath administered by, in all likelihood, the president pro tempore of the Senate, Chuck Grassley. Roberts will then administer a special oath required by Article I of the Constitution to the senators present: ‘‘I solemnly swear ... that in all things appertaining to the trial of the impeachment of Donald J. Trump, now pending, I will do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws: So help me God.’’

Meanwhile, a writ of summons will be delivered to President Trump. The writ will recite the impeachment articles and call on Trump to appear before the Senate, to file his answer to the articles, and to abide by the orders and judgments of the Senate in its consideration of them. Trump’s derisive tweets about the Senate process will give rise to the widespread inference that he has, in fact, received the Senate’s writ.

At 12:30 p.m. on the day designated for the return of the summons, the legislative and executive business of the Senate will be suspended, and the secretary of the Senate will administer an oath to the returning officer, testifying that he or she did indeed deliver the writ to Trump. Assuming that Trump declines to appear in person to deliver his answer, he will be defended by counsel of his choice, working in conjunction with the White House counsel’s office.

In this article, we attempt to imagine a Senate trial of Donald Trump given the rules under which such a trial will take place and given what we know or can reasonably infer about the ambient political environment in which the trial will happen. The goal is to think through the question of how House impeachment managers and lawyers for the president are likely to strategize litigation under the highly unusual rules that will govern it. Can Republicans dismiss the case quickly? Can Democrats force John Bolton and Mick Mulvaney to give the testimony both refused to give when asked by the House? Can Republicans move to turn the whole affair into a trial of Hunter Biden and his father? These questions, and others like them, involve the complex interplay of politics and quasi-legal proceedings in which Democrats will want to prove an actual case under a skeletal framework of rules that offers many degrees of freedom.

The Rules

Before thinking about how the respective parties are likely to try the case, let’s start with an overview of the rules themselves.

The Senate impeachment rules, as the imagined account above describes, choreograph the opening of the trial in some detail. They require that when the Senate receives notice from the House that it has appointed its managers to prosecute the impeachment trial, the secretary of the Senate must “immediately” inform the House that the Senate is “ready to receive” them (Rule 1). When the managers are introduced at the Senate bar and signify that they are ready to exhibit the impeachment articles, the sergeant at arms, at the direction of the Senate’s presiding officer, must issue the proclamation quoted above. Following the proclamation, the articles are to be exhibited, and the presiding officer of the Senate must inform the House managers that the Senate “will take proper order on the subject of the impeachment” (Rule 2). Following the presentation, the Senate must proceed to consider the articles no later than 1 p.m. the following day. The Senate shall “continue in session from day to day,” after the trial commences, unless the Senate decides otherwise, until a final decision is made (Rule 3). That decision can either be a final vote or a vote to adjourn the trial at any time along the way.

Once the articles are presented and the Senate is organized, the person impeached receives a “writ of summons,” stipulating the articles of impeachment raised and calling him to appear before the Senate at a time specified in the writ; to file his answer to the articles; and to abide by the orders and judgments of the Senate in trying him (Rule 8). If, after service of the writ, the impeached person fails to appear—whether in person or through his attorney—the trial shall proceed as if the impeached party pleaded not guilty. Similarly, if he appears but fails to file his answer, the trial shall proceed upon a plea of not guilty. If the impeached party pleads guilty, a judgment may be issued without any additional proceedings (Rule 8).

At 12:30 p.m. on the day scheduled “for the return of the summons” against the impeached party, the Senate shall suspend its other business and the secretary of the Senate must administer a prescribed oath to the officer designated to deliver the summons confirming that he or she did in fact do so (Rule 9). At that point, the person impeached must appear before the Senate to answer the articles against him (Rule 10). If he appears, or any person appears for him, the appearance will be recorded; likewise if he does not appear (Rule 10).

In keeping with the dictates of Art. I, § 3 cl. 6, the chief justice must preside when the president is impeached (Rule 4). So the rules require that the presiding officer of the Senate must provide the chief justice with the time and place fixed for the consideration of the articles of impeachment and invite him to attend (Rule 4). The last time a president was impeached, Chief Justice William Rehnquist wore a Gilbert & Sullivan-inspired robe striped with gold to the affair: a sartorial decision unlikely to be repeated in the near future. Upon the chief justice’s arrival in the Senate, the presiding officer of the Senate administers the oath to him, and he, in turn, administers a special oath to the senators present, as required by Art. I, §3, cl. 6 (Rule 3). The chief justice then presides over the Senate during the consideration of the impeachment articles and during the trial that follows (Rule 4).

So far, the rules present a series of detailed stage directions for the initiation of the trial process, but these details don’t have a lot of substantive implications for the progression of the trial. And where things turn substantive, they also turn vague, putting a great many important questions in the hands of the chief justice and whatever constellation of at least 51 senators can get together in coalition on any given matter.

Critically, and contrary to common mythology and parlance, the chief justice is not the “judge” in an impeachment trial. The Senate itself is both judge and trier of fact, and the chief justice serves as its presiding officer. The rules thus require the chief justice to direct “all forms of the proceedings” (Rule 7) and, in so doing, “to make and issue all orders, mandates, writs, and precepts authorized by the rules” (Rule 5).

Importantly, the chief justice may rule on questions of evidence—including, but not limited to, questions of relevancy, materiality, and redundancy of evidence and incidental questions (Rule 7). But the chief justice does not have to play this role, and he is not the final word on matters when he does. Should he decide that he wants to rule on a particular question, his ruling stands as the judgment of the Senate (Rule 7) unless a senator seeks a vote on the question—“in which case it shall be submitted to the Senate for decision without debate.” Should the chief justice not want to rule on an evidentiary question, he can simply submit it to a vote in the first instance (Rule 7). Upon all these questions, the vote must be taken “in accordance with the Standing Rules of the Senate” (Rule 7).

In other words, a huge amount in any Senate trial depends on two big variables: the attitudes and views of Chief Justice Roberts and, ultimately, which side controls 51 votes to either sustain or overrule his rulings or to rule on questions he declines to address. An important wrinkle here is that it takes 67 votes, not 51 votes, to change a rule—so one key question is whether a motion would require a waiver of an existing rule or whether it can reasonably be reconciled with the rules. If it requires a rule to be waived or dispensed with, the motion requires a supermajority. This issue came up during the Clinton impeachment trial, when a senator asked whether, under Rule 20, a simple majority of senators could vote to open the Senate doors during deliberations. Chief Justice Rehnquist ruled that, while the rule seemed ambiguous, such a motion would require a 67-vote majority to prevail given “consistent practice of the Senate for the last 130 years in impeachment trials.” Two senators subsequently introduced motions to open the doors of the Senate during deliberations, but they twice failed to muster 67 votes.

As this episode exemplifies, while there are no clear rules of evidence, there is a respectable body of precedent, particularly but not exclusively on evidence questions. This Congressional Research Service report from 1999 usefully lays out evidentiary precedents from Senate trials of judges. One should not expect senators to feel themselves bound by such precedents in the face of the expected momentary advantage to be gained by acting differently from the manner in which the Senate has acted in the past. But to the extent that Chief Justice Roberts himself rules on an evidentiary motion, prior practice will likely—as it did with Rehnquist in this episode—loom large for him, as it is the closest thing to law he will have to work with.

The Senate itself is far from powerless in deciding how the trial proceeds. It has the explicit responsibility of directing “all necessary preparations” for the consideration of impeachment articles (Rule 7). And it can “compel the attendance of witnesses”; “enforce obedience to its orders, mandates, writs, precepts, and judgments”; “punish in a summary way contempts of, and disobedience to, its authority”; and “make all lawful orders, rules, and regulations which it may deem essential or conducive to the ends of justice” (Rule 6). As noted above, any member of the Senate can ask that a formal vote be taken on an evidentiary question put to the chief justice (Rule 7). And while the rule has never been used before in the trial of an impeached president, only judges, the presiding officer of the Senate may also appoint a subcommittee of senators to receive evidence and take testimony on its behalf (Rule 11).

At 12:30 p.m. on the day of the trial, the legislative and executive business of the Senate is suspended, and the secretary of the Senate must give notice to the House of Representatives that the Senate is ready to proceed (Rule 12). The Senate shall then sit upon the trial of an impeachment at noon (unless the Senate chooses another time) each day until the trial is done (Rule 13).

The counsel for both parties—the House impeachment managers and the White House defense lawyers in this case—must be allowed to appear and speak (Rule 15). All “motions, objections, requests, or applications whether relating to Senate procedures or relating immediately to the trial (including questions with respect to admission of evidence or other questions arising during the trial)” made by either party must be addressed to the chief justice alone. Upon the request of either the chief justice or any senator, these motions must be communicated in writing and read at the secretary’s table (Rule 16). The subpoenas issued by both parties must employ the uncompromising language specified by Rule 25: “You and each of you are hereby commanded to appear before the Senate of the United States.... Fail not.”

Only one person may examine, and only one may cross-examine, a witness (Rule 17). Should a senator be called as a witness, he or she must be sworn in and provide his or her testimony standing in his or her assigned place in the Senate (Rule 18). Rule 25 specifies the precise oath to be administered to all witnesses. When a senator wishes to put a question to a witness, to a manager, or to counsel for the person impeached, or when the senator wishes to offer a motion or order, he or she must communicate the matter in writing and give it to the chief justice (Rule 19). The parties or their counsel may object to witnesses answering any question put forward and argue the merits. The ruling on any such objection must nonetheless accord with Rule 7 (Rule 19). And no Senator may “engage in colloquy” (Rule 19). This last rule, that senators actually have to shut up, is going to be tough for a lot of them.

During the trial, the Senate doors must be open—though, as noted, they have traditionally been closed during deliberation (Rule 20). Each side has no more than one hour to argue all “preliminary or interlocutory questions, and all motions”—unless the Senate orders otherwise (Rule 21). One person shall open the case on each side, though the final argument may be made by two people—unless ordered otherwise by the Senate (Rule 22). The House side will open and close the argument (Rule 22). When the doors are closed for deliberation, members can speak only once on one question; for 10 minutes or less on an interlocutory question; and for not more than 15 minutes on the “whole deliberation on the final question” of removal—unless the Senate decides otherwise (Rule 24).

Once voting begins, the chief justice shall first state the question; thereafter, each senator, as his or her name is called, shall rise and give the answer “guilty” or “not guilty” (Rule 23). There has been some talk of late about the possibility of a secret ballot. While such a rule could certainly be adopted, there is no provision for a secret ballot under the current rules, so it would require a supermajority to make it happen.

Once voting has commenced on any article, it must continue on all articles with the yeas and nays counted separately for each one. Voting on the articles of impeachment, assuming there is more than one, cannot be divided at any time during the trial (Rule 23). In keeping with the constitutional rule, a judgment of acquittal must be entered if two-thirds of the members present do not vote to sustain any article of impeachment. However, if the person impeached is convicted upon any article by a two-thirds vote of the members present, the “Senate shall proceed to the consideration of such other matters as may be determined to be appropriate,” in other words, his removal and disqualification from office. Once the Senate has issued a final decision, a certified copy of the judgment must be placed in the secretary of state’s office (Rule 23). Motions to reconsider the vote, whatever its outcomes, must be summarily rejected (Rule 23).

All orders and decisions may be executed immediately, assuming there is no objection. If there is an objection, the orders and decisions shall be voted on without debate in conformance with Rule 7 (Rule 24).

A motion to adjourn the trial can take one of two forms: It can be an adjournment for the day, or it can be a motion to adjourn the trial sine die (Rule 23), which ends the trial altogether and thus functions effectively as a motion to dismiss. A motion to adjourn may be decided without the yeas and nays, unless one-fifth of the members present demand them (Rule 24). Whenever the trial is adjourned, the Senate shall resume its legislative and executive business (Rule 13). The secretary of the Senate must record the proceedings of the impeachment as he or she would legislative proceedings and report in the same manner (Rule 14).

Notably absent from the rules is any discussion of what evidentiary rules apply. What’s the burden of proof? What evidence is admissible? What privileges does the Senate recognize? In practical terms, it is up to each individual senator to determine how consequential he or she finds the evidence against Trump to be. With respect to privilege, the answer is not entirely clear. Some observers, like Michael Gerhardt, have argued that there’s no role for executive privilege in a Senate trial and it would likely not be recognized by the courts. Others, like Charles Black, agree with the caveat that a claim of executive privilege will be more likely to succeed where privilege is asserted to protect substantive information that would harm national security interests. In practical terms, such questions—like all evidentiary matters—are up to the chief justice in the first instance and the Senate at large ultimately.

Gaming Out a Trial

Despite the appearance of granularity as to the theatrical elements of the trial’s opening, the Senate impeachment rules are kind of like the rules in a game of Calvinball. While default rules exist, they can be changed or reinterpreted, leaving more room for political gamesmanship than might appear at first glance—and in any event, the key rule holds that most major decisions are ultimately at the discretion of a vote by the body. In other words, the ultimate rule is that there are relatively few rules, all of them malleable.

The first broad point, therefore, is that the rules will tolerate just about any deal that senators can reach about what the rules should be. This is what happened during the Clinton impeachment. In 1999, Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott and Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle worked together and with their respective caucuses to negotiate a trial plan, which was subsequently submitted to the full Senate for a vote. The principal resolution, which passed unanimously, allocated the House managers and the president equal time to present before the Senate (up to 24 hours), limiting both sides’ arguments to the record. Following their presentations, the Senate had up to 16 hours to question both sides, after which point the Senate could debate whether to dismiss or to subpoena witnesses and to present evidence not contained in the record. As it played out, the motion to dismiss initially failed and the House managers then deposed three witnesses: Monica Lewinsky, Vernon Jordan and Sidney Blumenthal. Shortly thereafter, Clinton was acquitted.

While it’s hard to imagine Republicans and Democrats agreeing on a comprehensive governing set of rules for the trial, given how different their objectives are and how polarized the environment is, it’s less difficult to imagine all sorts of smaller deals or even a broader framework arrangement that would answer some of the questions we discuss below.

In gaming out how a Senate trial is likely to proceed in the absence of such a deal, it’s important to think about the rules in tandem with the apparent strategic objectives of the two sides. Because the president’s ultimate acquittal is a foregone conclusion, the House impeachment managers, and their Democratic allies in the Senate, will not be aiming for removal. Their goal will be to lay out as clear and as vivid a record of the president’s conduct as possible—which is to say to get as many key witnesses as they can to testify, and to thereby maximize the president’s electoral discomfort and the electoral discomfort of those Republican senators who will ultimately vote to acquit him.

The president’s defenders, by contrast, will want to minimize the presentation of evidence against Trump and, to the extent they can, to change the subject from Trump’s bad conduct to other things. For example, as Sen. Lindsey Graham’s recent comments suggest, they might try to shift the frame to the Bidens and Burisma; they might also want to talk about the Steele dossier and the Russia investigation and supposed Ukrainian interference in the 2016 election. The more they can shift the conversation toward conspiracies against the president, the more they might argue that Trump’s own actions were not lawless but were reasonable defensive moves under the circumstances.

Ideally, the president would want to win on a motion to dismiss and jettison the whole trial entirely. So, first things first. Does there have to be a trial? It would be pretty hard to worm out of holding any trial at all. Art. I, § 3 cl. 6 gives the Senate sole power to try impeachments, suggesting though not specifically saying there is a duty to do so, while Rule 3 presumes that a trial will commence after the articles are presented. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell acknowledged as much recently when he said that the rules “are very clear when it comes to the trial.” Of course, there’s a possibility he could backtrack on this statement. McConnell might, for example, argue that the aforementioned provisions convey the Senate’s power, not its inexorable obligations. As Bob Bauer has hypothesized, McConnell might try and get the Senate to reinterpret the rules in line with that interpretation, which requires only 51 votes. But such an approach seems unlikely, especially because if McConnell has 51 votes to make the trial go away, there’s a less-controversial mechanism under the rules to do exactly that.

Indeed, just because there has to be a trial does not mean there has to be an extended trial. Republicans could seek a quick dismissal after a few days by moving to adjourn the trial sine die. Indeed, judging from his statements, this may be McConnell’s preference. The key question is whether 51 Republicans would go along with that or whether enough would side with the Democrats to prevent a dismissal without the full presentation of the evidence. Even if the goal is to acquit Trump when the sun sets, some senators might believe that the legitimacy of the constitutional process demands more than perfunctory consideration of the case against him. And some—like Mitt Romney, for example—are publicly disturbed by Trump’s conduct. So the first key question is whether McConnell has 51 votes to make the trial go away quickly or whether the Democrats have 51 votes to keep it going.

Short of a quick dismissal, we’re going to see fights over evidence. The goal for the president’s lawyers will likely be to limit the introduction of evidence to what we already know. Democrats, by contrast, will likely want not only to present the testimony they obtained in the House investigation but also to use the trial to get to some of the witnesses who stiffed the House: John Bolton, Mick Mulvaney, Rudy Giuliani, and, depending on whether the House includes material from the Mueller report in the articles it sends over, Don McGahn. Whether the Senate trial involves such new releases or just the golden oldies from the House hearings will play a big role in determining how riveting it is as television. And the answer to that question depends pervasively on whether Democrats both hold together and can convince a handful of Republicans to vote their way on evidentiary motions.

The bluntest means of limiting the record would be for Republicans simply to vote to limit the evidence to the existing record. It’s the Senate’s prerogative under Rule 6 to “make all lawful orders, rules, and regulations which it may deem essential or conducive to the ends of justice.” So imagine a motion to simply conduct arguments based on the established House record. Assuming that Chief Justice Roberts does not rule on the question, which he has discretion to do under Rule 7, the question would be put to the Senate either for a simple majority vote or for a supermajority vote, depending on whether Roberts regarded the motion as reinterpreting the Senate rules on witnesses or fundamentally changing them. There is no prospect of Republicans managing a supermajority for such a motion, but it’s not inconceivable that they could muster 51 votes for it.

If we assume that the Republicans do not have the votes to limit the record, the next question becomes whether Democrats have 51 votes to call the witnesses they want or whether Republicans have the votes to sustain challenges to witnesses who could expand the record with new information. This may be—other than the question of the motion to adjourn sine die—the key question in the trial. While witnesses have defied summonses from the House, it’s hard to see how they could defy the Senate as a body with the chief justice presiding, especially in the face of the explicit inherent contempt powers the rules convey. Moreover, assertions of privilege by these witnesses would be subject to immediate ruling by the chief justice, or by the body itself, so the same coalition that called them could presumably reject such claims.

But what’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander, and if Democrats can expand the record to allow the introduction of new evidence, Republicans can do the same—subject to the same rule of 51 votes. Given that the Senate has 53 Republicans, that’s an easier lift for the president’s defenders than it is for impeachment managers. Can the president’s defenders call in Joe and Hunter Biden as witnesses? Democrats might seek a ruling from the chief justice on the relevancy of such testimony. While Chief Justice Roberts might decide to answer, he might also just punt it to the Senate. Either way, the ultimate relevancy determination is made by a majority vote of the body. (Note that there is fairly extensive precedent on the subject of the relevance of testimony, though most of it involves challenges to lines of questioning, not to witnesses themselves.)

One interesting question here is whether the Democrats need to flip four Republicans to reach the magical threshold of 51 to prevail on motions or only three, leaving the Senate perfectly divided. The answer turns out to be complicated. The reason is Vice President Mike Pence. Art. 1, § 3 cl. 4 provides as a general matter that the vice president shall be the president of the Senate but shall have no vote “unless they be equally divided.” Normally, then, Democrats need 51 votes to prevent Mike Pence from breaking a tie in the Republicans’ favor. But in the situation of an impeachment trial of the president, the vice president is not the presiding officer because of his obvious conflict of interest. The Senate impeachment rules are silent on the question of whether the chief justice casts a tie-breaking vote, but during the Andrew Johnson impeachment, Chief Justice Salmon Chase did so twice. So the answer is probably that Roberts could break a tie—meaning that on a matter submitted to the Senate without an initial Roberts ruling, Democrats would need to flip three Republican senators if Roberts agrees with them or four if he does not. Likewise, if Roberts rules on a motion as an original matter, it would require 51 votes to overturn his ruling—meaning that Democrats would need four Republicans to flip to overturn a Roberts ruling, but only three to sustain one.

The bottom line is that this trial will be all about who can count to 51—and all about how active the chief justice wants to be in determining the default rulings if senators fail to do so. Will Roberts seek to emulate his predecessor Rehnquist’s hands-off approach (according to one book on the impeachment trial, Rehnquist brought court work and playing cards to pass the long periods of downtime)? Or, will he be more like Chief Justice Chase and take an active role in the Senate trial process—and how will senators react if he does this? With only two prior presidential impeachment trials to work from, there’s no strong norm here. So Roberts could also try to chart a course of his own.

-final.png?sfvrsn=b70826ae_3)