Inching Closer to a Showdown Over the Fate of Captured Islamic State Fighters

More than 600 Islamic State fighters from a variety of countries are being held by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Syria, but no one thinks this situation can last. Frantic diplomatic negotiations have borne little fruit so far, and it appears a two-pronged stopgap solution may be in the works. Buckle up.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

More than 600 Islamic State fighters from a variety of countries are being held by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Syria, but no one thinks this situation can last. Frantic diplomatic negotiations have borne little fruit so far, and it appears a two-pronged stopgap solution may be in the works. Buckle up.

This is an important story that has been slowly heating up during 2018. Steve Vladeck and I discuss it frequently on the National Security Law Podcast (see this episode from late July, for example), and journalists like Charlie Savage have done some amazing work shedding light on the facts on the ground. For those who have not been following it, here are the important things to know about the state of affairs up until now:

First, there are of course large numbers of captured Islamic State fighters. It’s just that we don’t do the detaining ourselves (though when John Doe turned up in SDF custody as a U.S. citizen, he did end up in U.S. military custody and remains there to this day). Instead, captures in Iraq have been dealt with by the Iraqis (through a criminal prosecution model that results in extraordinarily-rapid capital punishment in a great many cases involving extraordinarily-little process, thus serving as a stark reminder that military detention for the duration of hostilities traditionally was conceived (for very good reason) as a more humane alternative than resort to criminal prosecution). And captives in Syria, when made by U.S. allies in the SDF, end up in the makeshift detention system that SDF has cobbled together (and which Savage documents well in the article to which I linked above). All of which has proven to be relatively stable, staying out of headlines.

Second, the SDF appears to be in serious trouble as the Assad regime (with massive Russian and Iranian help) has stabilized its position and as President Trump has begun foreshadowing an American withdrawal (or at least reduction in effort). Sooner or later, it seems clear that the SDF will be inclined to reallocate its limited resources away from detention operations, and it may well be forced out of the business simply by virtue of territorial loss. No one thinks, at any rate, that the SDF facilities are a long-term solution.

Third, the SDF detainee population is packed with fighters who are not Syrians, but instead come from around the world (including many European citizens). So perhaps they could just be sent home, to face some fate there? There have been some transfers along these lines. But it appears that many if not most governments involved do not want their people back. The United States has been engaged in intensive diplomacy to change minds, reportedly, but without much progress to this point.

Fourth, there are two of these detainees who stand out as a special case: people who once were British citizens but have now had their citizenship stripped and are stateless. These two are part of the group of particularly-heinous Islamic State members known as the “Beatles,” and they are alleged to have direct involvement in several atrocities (including the murder of James Foley). These distinctions combine to cast a spotlight on their fate, and give the United States a particular interest in insuring that justice is done.

To sum up, things have been at an impasse for a while. Which is where today’s long and thorough report from Courtney Kube, Dan De Luce, and Josh Lederman for NBC News comes in.

NBC reports that the Trump administration is considering a two-prong solution.

First, the bulk of the foreign fighters would be transferred to Iraq for further intermediate-term custody, either under some form of law of war-based interim detention that might buy time until home country governments can be talked into cooperation, or perhaps instead to face some form of prosecution in Iraq itself. The Iraqis apparently have not yet agreed, notably.

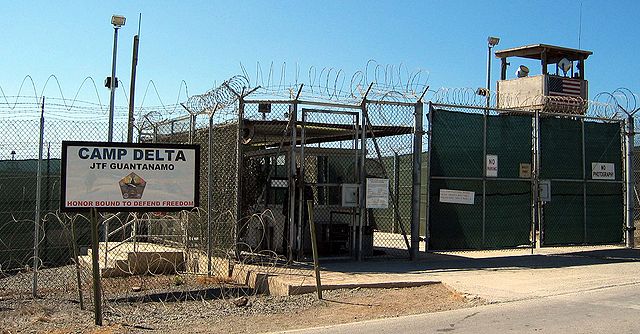

Second, as to the two Beatles: NBC says the White House is very much thinking about bringing those two into American custody. Which would be fine if the goal was to put them on trial for their horrific crimes. But the plan, instead, may be to take them to GTMO. I explained in February that the best hope for justice as to these two is a federal court prosecution in the United States. That remains true, and happily the call to send the men to GTMO seems this time not to include the notion that a military commission trial somehow could deliver more certain or swifter justice. So why send them to GTMO at all? The only plausible justification is a hoped-for period of U.S.-administered interrogation before sending the men on to prosecution. Given how long they’ve been in custody, it’s not obvious how useful this would be in the best of circumstances. But anyway, it flat-out cannot work absent a new statute overriding existing law barring transfers of anyone from GTMO into the United States. Meanwhile, even if that is overcome through a legislative miracle, this approach increases the risk of problems for the eventual prosecution (though those risks are not significant if the interim period is kept short enough). More significantly, the GTMO-for-a-month approach ensures instant habeas litigation challenging the fundamental legal claim for the entire conflict with the Islamic State (that they are within the scope of the 2001 AUMF). That could be mooted, presumably, if the men were then transferred out to civilian custody relatively quickly. But the risk of an unfavorable preliminary ruling is real enough, and would grow as time passed. And of course it is far from obvious that a short stay at GTMO would yield better cooperation than would a rapid and effective capital prosecution.

The best path remains: move straight to prosecution in a federal civilian court.

.jpg?sfvrsn=d5e57b75_7)