The Innovation-Security Conundrum in U.S.-China Relations

If one defines technology as anything that extends human capability, it takes only a short logical leap to conclude that nearly any advantage in technological capability over a competitor entails potential military advantage over that competitor.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

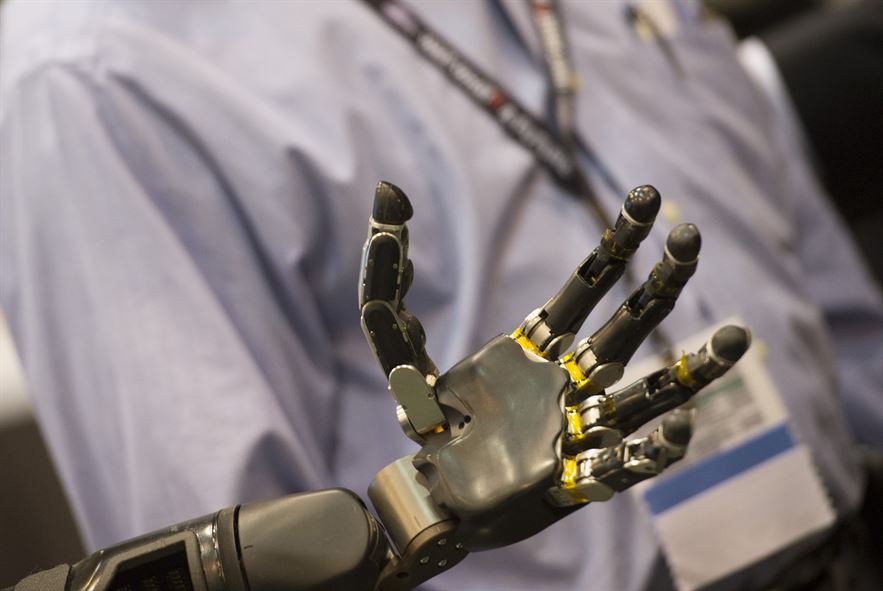

If one defines technology as anything that extends human capability, it takes only a short logical leap to conclude that nearly any advantage in technological capability over a competitor entails potential military advantage over that competitor. This is especially so in today’s era of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics, where the distinction between technologies designed for commercial and military use is blurred and the technologies under development will be foundational to a multiplicity of as-yet-unforeseen applications.

This reality goes to the heart of a defining feature of U.S.-China relations: the increasing entanglement of economic and national security concerns. In China, the lines between the Communist Party-led government and the market are often unclear and, by some estimates, are becoming murkier by the day. In addition, the party-state embraces an expansive conception of national security that incorporates economic welfare and an array of other objectives. This blending—of government and market actors, of national security and commercial interests—informs myriad tensions between Washington and Beijing. China has erected barriers to market access for foreign firms, in some cases through vague and intrusive regulations justified on cybersecurity or national security grounds. Chinese entities with links to the government have engaged in cyber-enabled theft of intellectual property that frustrates the emerging norm seeking to restrict state-sponsored cyber theft for commercial purposes. Chinese industrial policies promote “civil-military integration,” the development of “national champion” tech companies and the acquisition of foreign technology—the latter representing a central basis for the Trump administration’s latest tariffs on Chinese imports. Even China’s Belt and Road Initiative, with its apparent merging of economic and geopolitical objectives, underscores the degree to which Beijing treats economic and security goals as two sides of the same coin.

But China’s government has no monopoly on the muddling of security and economics. President Trump’s economic nationalism has met plenty of criticism but has also been buttressed by an emerging bipartisan consensus on the need for more toughness with China and reciprocity in the bilateral relationship. Though tempting, it is too simplistic to dismiss the Trump administration’s conflation of objectives by pointing to the suspect rationale behind its tariffs on steel and aluminum in the name of national security, or by highlighting the lack of clarity in the recent debate over how harshly the United States should punish Chinese telecom company ZTE—at once a sanctions scofflaw and settlement violator, a bargaining chip in the unfolding U.S.-China trade war, and an alleged threat to U.S. national security. Instead, these episodes may obscure a challenge that is deeper and more fundamental.

A central illustration of the challenge can be found in the text of a bill making its way through Congress that would reform the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, or CFIUS. The legislation, known as the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), represents an important effort to strengthen the interagency body that scrutinizes foreign direct investments to identify national security risks. One of few reform measures enjoying overwhelming bipartisan support, FIRRMA is largely informed by concerns over Chinese state-linked investment in cutting-edge U.S. technologies. The legislation is part of the National Defense Authorization Act in the Senate and a standalone measure in the House, where it recently passed 400-2. The Wall Street Journal reported on July 19 that House and Senate negotiators had reached a deal on final text that could go to a vote as early as this week.

As drafted, the legislation would (among other things) broaden CFIUS’s jurisdiction to include non-passive minority-position investments in “critical technology” companies. It would also expand the U.S. export-control regime by creating an interagency process to identify and limit the transfer of “emerging and foundational technologies.”

The legislation defines critical technology as “technology, components, or technology items that are essential or could be essential to national security.” These would include “emerging and foundational technologies” that are essential to U.S. national security. The bill would not outright prohibit foreign investment in critical or emerging and foundational technologies, nor would it completely bar the transfer of such technologies to foreign entities. It would, however, subject these transactions to CFIUS scrutiny and enhanced export control regulation (with several exceptions, including for the sale and licensing of finished products and associated technologies that a U.S. company generally makes available to its customers). This will leave wide discretion to officials tasked with identifying such technologies and preventing them from getting into the hands of foreign adversaries.

What makes these provisions necessary is precisely what will make them so challenging to administer. AI and machine learning technologies, robotics, blockchain, virtual and augmented reality, and fintech, to name a few, are poised to transform economies and lives the world over. There has been a proliferation of commentary on the emerging U.S.-China rivalry in AI and advanced tech in recent months. The coming era has been pitched as one of epic competition between “digital authoritarianism” and liberal democracy. Amid these developments, one thing is certain: Technologies built on the foundations of AI will create engines of innovation for decades to come, feeding new applications and end-use technologies in unpredictable ways.

In such a world, what principles should guide federal agencies such as the Commerce Department in judging whether an early-stage technology “could be essential” to U.S. national security? How will officials discern which new technologies will serve as “foundations” for future technologies in ways that render them essential to national security? In practice, will it mean that everything AI-related will be off-limits to Chinese venture capital firms? And how to think about the strategic costs (in lost access not only to capital but also to data, talent or manufacturing capacity, perhaps) of curtailing Chinese investment in industries that are crucial to future U.S. economic prosperity—itself an important element of national power and strategic advantage?

FIRRMA’s drafters have made no secret of the fact that they designed the bill with the Chinese government and its weaponization of investment in mind. The latest version of the Senate bill expresses the “sense of Congress” that CFIUS may consider in its national security reviews whether a transaction involves a “country of special concern” (read: China) that has “a demonstrated or declared strategic goal of acquiring a type of critical technology or critical infrastructure that would affect United States technological and industrial leadership in areas related to national security.” In an age when AI is fueling so many dual-use technological innovations, it is fair to wonder which types of emerging technology will not affect U.S. technological leadership in an area “related” to national security.

In short, Congress and the executive branch are increasingly aware that the economic and security implications of AI and other emerging technologies are all but impossible to disentangle. That this recognition may result in the strengthening of CFIUS and the export control regime is an overdue and welcome development given the strategic stakes.

At the same time, however, as President Trump escalates his trade war with China, the United States finds itself in an awkward position, arguing that China should open its economy (for example, by removing joint venture requirements that lead to forced transfer of technology from foreign to Chinese firms) and end its policies of state-directed technology acquisition (for example, by ceasing to give Chinese firms preferential access to capital for overseas acquisitions or by cracking down on commercial cybertheft). If artificial intelligence and the follow-on innovations it generates are as crucial to national security as Washington is beginning to realize, why wouldn’t China’s leaders consider it a national security imperative to double down on state intervention to support Chinese technology acquisition and advanced manufacturing capabilities? Indeed, if Chinese President Xi Jinping drew one lesson from the Commerce Department’s threat to put ZTE out of business by cutting off its supply of U.S. semiconductors, this may well have been it.

While the conceptual entanglement of economic and national security interests may be unavoidable, the implementing details of U.S. reforms to CFIUS and export control systems—as well as how they are explained by American officials to Chinese counterparts—will matter greatly. Anticipating the risk of shooting oneself in the foot by isolating U.S. technology from the rest of the world, the Senate version of FIRRMA instructs that the interagency process for export control identification should take into account, among other factors, the effect that technology export controls would have on the development of such technologies in the United States, as well as whether imposing controls on the transfer of a technology will actually be effective in limiting foreign countries’ access to that technology. These are weighty technical burdens for those who implement the new system, and the private sector will have an important role in helping U.S. government officials understand the risks and potential applications of the technologies and transactions they will increasingly be called upon to evaluate for national security sensitivities. At a minimum, that such decisions will be made through interagency processes on a case-by-case basis is far preferable to the kind of sweeping prohibitions on Chinese investment that Trump had contemplated under the authority of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act before reaffirming his support for FIRRMA.

The U.S. economy may have been a bit too open for a time; China’s economy remains far too closed. U.S. officials must bear in mind both that maintaining U.S. technological leadership requires the maintenance of an open economy with capital flowing to American innovation and that China’s plan to overtake the United States in science and technology development is more ambition than accomplishment to date. The impending reform of CFIUS need not preclude opportunities for U.S.-China cooperation in this space.

In recent years, Washington has been coming to terms with dashed hopes about China’s trajectory—its authoritarian repression at home, its assertiveness abroad and the outsized role of the state in the world’s second-largest economy. Meanwhile, U.S. policymakers have come around to the need for more state intervention at home in the name of national security to guard America’s technological edge—the very capability Beijing sees as crucial to its own long-term security and its transition to a more sustainable economic model. In a world increasingly shaped by AI-based innovations whose future dual-use applications and successor technologies will exceed the limits of today’s predictive capacity, the challenge of maintaining a functional distinction between national security and economic interests will not soon abate.

Editor’s note: Shortly after this article was published, the final version of FIRRMA was posted online as part of the Fiscal 2019 National Defense Authorization Act conference report. FIRRMA is in Title XVII of the NDAA, the text of which can be found here. (FIRRMA begins at pg. 1362.)