Intelligence and Public Dissent: A Response to 'The Dangers of a Loyalist Director of National Intelligence'

Editor's Note: Austin Carson's response can be read here.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor's Note: Austin Carson's response can be read here.

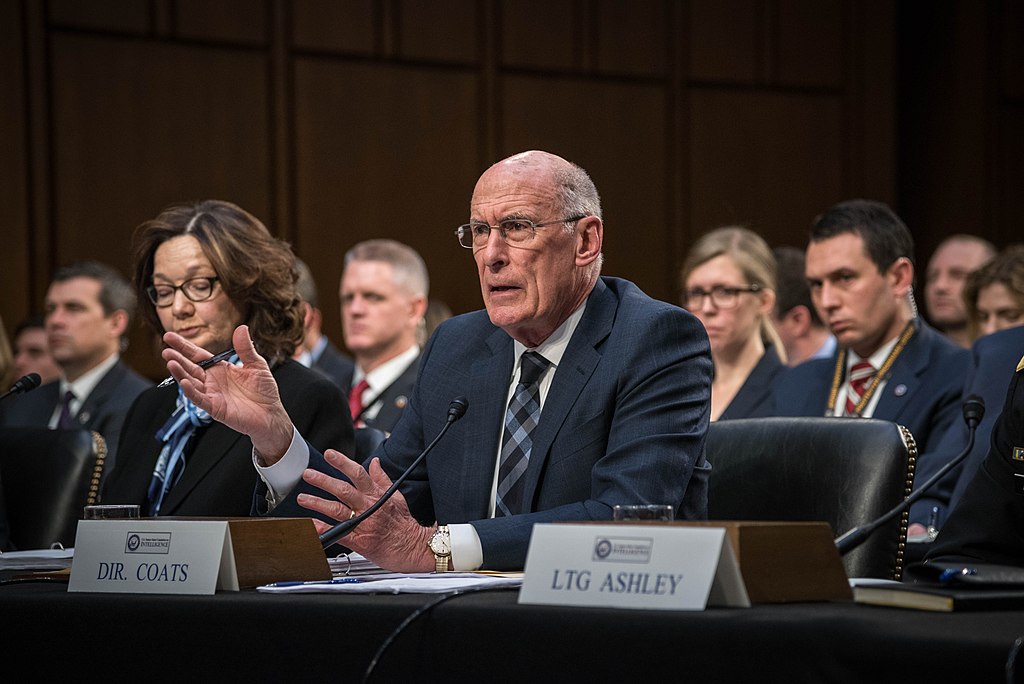

In a characteristically thoughtful piece in Lawfare, Austin Carson warns about the dangers of intelligence politicization in the Trump administration. He is concerned that the president may decide to replace the acting director of national intelligence, Joseph Maguire, with a political loyalist. When the position came open in the summer, Trump’s first choice was Rep. John Ratcliffe (R-Tex.), a strong supporter with very little intelligence experience. Though Ratcliffe removed his name from consideration, Carson worries that Trump may yet indulge his “reflex to nominate a loyal Republican supporter.”

Carson is right to be worried. Elevating yes-men to positions of leadership is a pernicious form of politicization. Rather than attempting to pressure career intelligence officers to bend to political pressure—the kind of thing that leads to scandal—manipulation by appointment works by putting friends and allies in positions of power. This can skew the tone and content of intelligence products and marginalize alternative views. It can also undermine morale in the workforce if analysts believe their leaders do not care about their work.

But Carson doesn’t stop there. In this case, he writes, intelligence officials should publicly break from their political bosses. Doing so will reassure anxious intelligence professionals who are vulnerable to policy meddling. It will also send a powerful signal of continuity at a time when domestic and international observers see chaos and uncertainty in American foreign policy. Public dissent will serve as a reminder that U.S. interests are deeper than any given administration, and that U.S. commitments will endure.

To those who are most concerned about the direction of the Trump administration, these arguments are intuitively appealing. Intelligence officials enjoy a special kind of authority because they possess secret knowledge. (People are more inclined to believe in assessments when they are classified.) The intelligence imprimatur also matters because the community has long cultivated a reputation for staying outside the political fray. Intelligence assessments focus on foreign affairs and usually steer clear of domestic fights. For these reasons, the director of national intelligence is not just another voice in Washington’s great political cacophony. Perhaps the director could use his or her special position, choosing the path of loyal opposition and restoring balance to the policy process.

Unfortunately, history does not provide much support for this claim. Since intelligence leaders began coming out of the shadows in the 1960s, their pronouncements have tended to align with policy preferences. Instead of providing the kind of stabilizing dissent that Carson seeks, they have amplified White House statements. Here’s why: If policymakers expect intelligence officials to speak out, they have powerful incentives to control what they say. And while intelligence agencies may want to speak truth to power, it is very difficult for intelligence leaders to resist sustained pressure from above. The result is that public dissent will not safeguard the integrity of the intelligence community. It will lead to more politicization.

Party politics also loom over any decision to go public. Dissent is red meat for political opponents, who exploit the persuasive power of secret intelligence for their own purposes. This in turn fuels suspicion among policymakers, especially those who already view the intelligence community as an obstacle, and risks turning intelligence into a partisan football. Several years ago I wrote about the problem of partisan intelligence, warning that the process could “align certain segments of the intelligence community with certain parties and politicians.” I have grown increasingly alarmed since that time as intelligence leaders have made it a habit to speak out on highly charged policy issues. The substance of their statements is not important. What matters is that the public has become accustomed to hearing them—and partisans have come to view intelligence as a cudgel they swing at one another.

Secret intelligence sits uneasily in a democracy. Secrecy is necessary for intelligence but antithetical to oversight. Navigating the opposite demands of secrecy and accountability requires a combination of diligence and good faith among intelligence leaders, policymakers and congressional overseers. Managing the process is difficult in the best of times—and these are definitely not the best of times. Intelligence officials may be tempted to use their credibility to push back in public, but they will not help matters through displays of public dissent. If they think policies are wrongheaded, they may feel an urge to speak out. They should resist the urge.