Interpreting the ‘Twitter Files’: Lessons About External Influence on Content Moderation

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

In the first installment of the “Twitter Files,” Matt Taibbi, a journalist covering Elon Musk's release of internal documents from Twitter, proclaimed the files to be a “Frankensteinian tale of human-built mechanism grown out the control of its designer.” While Taibbi's description may have been dramatically crafted for his readers, a better tale than Frankenstein to describe the files might be the parable of the blind men and the elephant. The releases give only a very narrow view of the broader, complex reality and encourage the reader’s imagination to fill in the details.

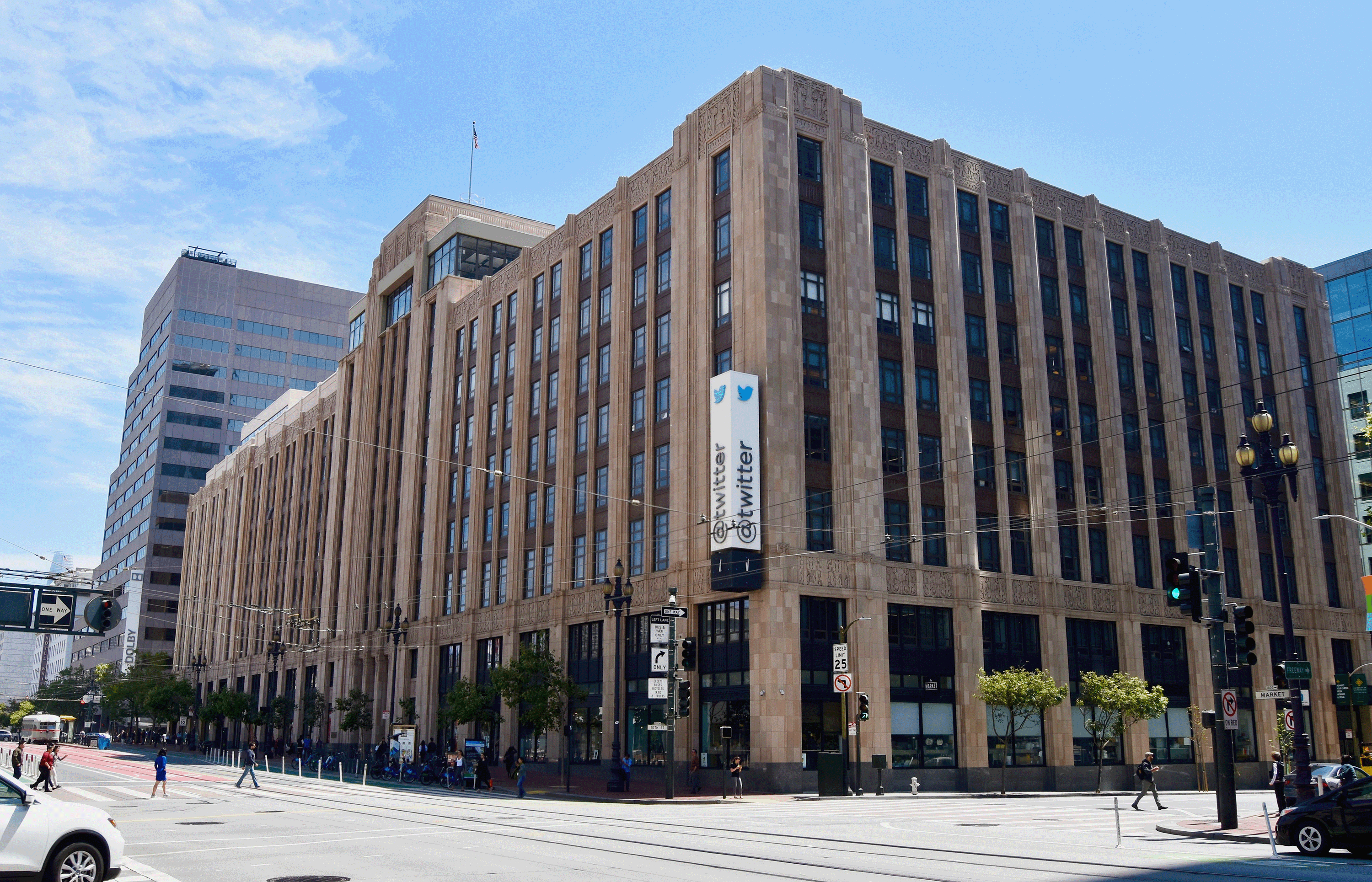

Others have made a variety of critiques of the Twitter Files, regarding both form and content. Despite their faults, however, the files give a rare window into the inner workings of a social media platform. Taibbi and other Twitter Files contributors have used internal Twitter communication to portray a platform susceptible to outside influence, a fact that biased its moderation decisions with a liberal slant. Our organization, the Clemson University Media Forensics Hub, was a subject of one recent Twitter File thread, and so with insider knowledge we want to help open the window a little wider and offer some necessary context.

The Twitter Files have encouraged a recent backlash of fear regarding government overreach, suppression of free speech, and influence by U.S. intelligence in platform content moderation. What the files show us, however, is that taking input from outsiders, including the government, isn’t the problem Taibbi suggests. Far from it. External voices can, and have, helped to balance the platforms’ own inherent biases.

The files have explored a range of issues Twitter executives needed to wrestle with, mostly related to content and account moderation. The first release in early December addressed the decision-making around the Hunter Biden laptop story—and since then, the files have gone on to explore topics ranging from Twitter’s decision to suspend Donald Trump’s account to how Twitter may have aided the Pentagon in a “covert online psyop campaign.”

A January installment of the Twitter Files, written by Taibbi, explored the relationship between Twitter and the U.S. intelligence community, including the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and the State Department’s Global Engagement Center. We were surprised to find that we at Clemson’s Media Forensics Hub—a small research lab at a mid-sized, land-grant university in the Southeast and not a part of the U.S. intelligence apparatus—were one of Taibbi’s central talking points in this thread. Taibbi presented us as another force, like the FBI, pushing Twitter to make attributions of Russian disinformation. It’s true that we have engaged with Twitter periodically over the past several years regarding foreign influence operations on the platform. Our appearance in the files, however, was only one side of one piece of a years-long dialogue. We learned a great deal about platform moderation from these exchanges, far more than is presented in the Twitter Files.

The files, and how they are being interpreted, tell us much about how society views the platforms as well as how the platforms view their own role in civil society and in relationship with the government. Based on the online response to this recent thread, many readers of the files were apparently shocked that U.S. intelligence (and others) would provide social media platforms with information and attempt to have a voice in moderation decisions. Tucker Carlson has called what was revealed in Taibbi’s release about Twitter’s relationship with the intelligence community “prima facie illegal ... the government cannot censor political speech.” Ben Shapiro has suggested it is evidence that Twitter was being “manipulated from the outside by the government and by the media.” But while U.S. intelligence may have overstepped in some cases (such as possibly seeking support for their own operations abroad), much of what the files show in this case is simply mechanisms by which light is being cast on possible foreign information operations. Far from illegal, working with U.S. platforms to stop foreign information operations in this way is exactly what we should expect from the government.

Engaging with experts from outside the organization to assist with the moderation process offers a variety of benefits. Outside groups come with skills and information the platforms may lack. The government may, for instance, have classified intelligence. Many nongovernmental organizations that work with the platforms offer linguistic and regional expertise, including Venezuela’s Cazadores de Fake News or Georgia’s Myth Detector. Academic research teams, like ourselves, offer technical insight and alternative approaches to analysis.

One could be forgiven for assuming that the platforms are significantly more knowledgeable and well-resourced than they are. In reality, platforms’ trust and safety teams are often too small and too overworked. Team members are more likely to have gotten their job because they have above-average technical skills rather than, for instance, in-depth knowledge of the politics and culture of Myanmar. To best fight modern information operations takes a broader toolkit than the platforms have alone, a toolkit that may include anything from extremely specific political and cultural knowledge to on-the-ground intelligence. Foreign nations, including China, Russia, and Iran, are waging an ongoing information war on the West. The platforms cannot and should not be left to fight it alone.

That said, each platform should remain the final arbiter of which content and accounts are moderated on its system and how it is done. There is a difference between receiving government counsel and following government orders, and nothing in the files indicates the latter has been done. The platforms, after all, have access to internal, technical information not available to outsiders and, importantly, in most cases currently have no legal obligation to suspend accounts or moderate content. With that in mind, and despite the concerns of pundits, the files do not actually show Twitter being compelled to act against its will. In fact, the files show several instances of Twitter pushing back against outside recommendations regarding moderation and attribution. Outside groups do have their own agendas, after all. Government agencies, for instance, may have political motivations, as the files demonstrate was Twitter’s concern in the case of the U.S. Global Engagement Center. Outside groups also have levels of risk tolerance that differ from those of the platforms; the downside of shutting down the wrong accounts may be higher for Twitter than it is for the FBI. Differing agendas cause inevitable tensions, which are on display in the files.

We need to be careful not to surrender too much ground to the platforms, however. They also have agendas that may not always align with what is best for society. Like any financially motivated corporation, platforms are often incentivized to hide things and make problems seem smaller than they really are (as the files show may have been the case at the start of Twitter’s Russia investigation). Financial realities also do not always incentivize what some observers may consider properly staffing or innovating the fight against clandestine foreign-influence operations. Finally, of course, the Silicon Valley workforce profile and culture may lead to somewhat leftward-leaning political motivations that could lead to uncharitable or unconscious biases in enforcement decisions.

Similarly, let’s not conflate the platforms’ right to make decisions regarding moderation of content with the right to make claims about what that moderation means and attribution of coordinated, inauthentic activity. We appeared in the Twitter Files when Taibbi shared internal correspondence between Twitter executives discussing our work. Those executives were not concerned about moderation recommendations we made. They had already permanently suspended all of the accounts we had identified to them as being part of a coordinated information operation. They were frustrated that we had worked with the media and again attributed these accounts to the Russian Internet Research Agency.

This was not something we did lightly; our attribution was based on many years of research and the development of specific techniques to identify coordinated Russian activity on Twitter. Nor was it the first (or last) time we would attribute accounts to Russia—part of the reason for Twitter’s frustration with us. We had previously shared our attributions with journalists at NBC as well as CNN, both of whom listened to and shared our professional judgments with the public. CNN found our arguments so compelling, in fact, that Clarissa Ward, CNN’s chief foreign correspondent, traveled to West Africa to uncover a Russian troll farm operating in the guise of an NGO pretending to help educate children. But Twitter never sat down with us to learn how we made our attributions. An “analytical exchange,” referenced in the internal communication from Twitter’s former head of trust and safety, Yoel Roth, never took place. The files show that Twitter viewed us as an outsider that needed to be managed rather than as a possible resource to contribute to a common goal.

The root problem may have been that “common goal.” Social media platforms’ incentive to attribute content to foreign operations continues to be low. Why wouldn’t it be? They certainly don’t want to fuel yet another story about trolls and scare users away; competition is already undercutting their user base. In fact, the same weak incentives the platforms face to disclose foreign influence may even lead them to hold too close to the vest the data that others would need to make those attributions. Relative to most other platforms, Twitter is praiseworthy for making itself accessible to researchers. We don’t know if Musk will continue these policies; he may have different incentives than the previous leadership. Differing incentives, however, is exactly why it is so important for the platforms, the government, and civil society, each in their own way, to contribute to the moderation process.

A close examination of the Twitter Files doesn’t show a Frankenstein’s monster “grown out the control of its designer.” The truth is much less dramatic. More simply, the files show understandable problems with systems plagued by conflicting interests. The villagers don’t need to grab their torches and pitchforks just yet. The communication that the files demonstrate between the platforms and outside groups, including U.S. intelligence, is nothing to be afraid of. On the contrary, when done correctly, this communication can foster balance and a safer social media experience for everyone. The Twitter Files certainly show, however, that so far these collaborations have often been ad hoc and distrusted. We have work to do, but it is work worth doing.