The Iranian Revolution and Its Legacy of Terrorism

The 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran has proved one of the most consequential events in the history of modern terrorism. The revolution led to a surge in Iranian-backed terrorism that continues, albeit in quite different forms, to this day. Less noticed, but equally significant, the revolution provoked a response by Saudi Arabia and various Sunni militant groups that set the stage for the rise in Sunni jihadism. Finally, the revolution sparked fundamental changes in American counterterrorism institutions and attitudes.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran has proved one of the most consequential events in the history of modern terrorism. The revolution led to a surge in Iranian-backed terrorism that continues, albeit in quite different forms, to this day. Less noticed, but equally significant, the revolution provoked a response by Saudi Arabia and various Sunni militant groups that set the stage for the rise in Sunni jihadism. Finally, the revolution sparked fundamental changes in American counterterrorism institutions and attitudes.

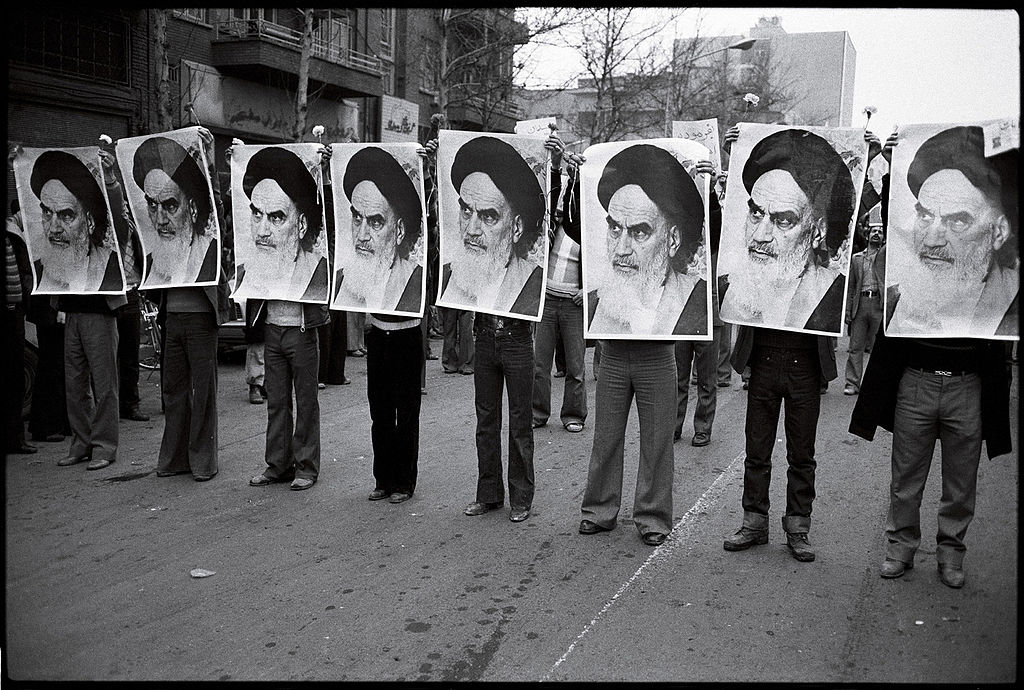

The new clerical regime in Iran initially viewed the world in revolutionary terms. Tehran’s leaders saw foreign policy through the lens of ideology, downplaying the strategic and economic interests of the country in pursuit of an Islamic revolution. In addition, like many revolutionary states, the new regime overestimated the fragility of neighboring regimes, believing that their people, too, would rise up and that they were ripe for revolution. The charisma of Iran’s new leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the compelling model of religious activism he offered, and the numerous ties among Shiite community and religious leaders in Iran to Shiite leaders in other countries led to a surge in militant groups in Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and other states that looked to Iran as a model for a Shiite revolution.

In addition, Iran declared its revolution an Islamic revolution, not just a Shiite one; it hoped to inspire Sunni Muslims as well. Although many Sunni militants saw Iran’s Shiite theology as anathema, the idea of a religious revolution was compelling and gave new energy and hope to existing organizations. The Iranian revolution helped inspire the assassins of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in 1981 and the Hama uprising in Syria in 1982.

The new regime’s ideology and misperceptions had several consequences. First, the new leaders often instinctively aided like-minded revolutionary groups, even when those groups had relatively little chance of success. So they supported the Islamic Liberation Front of Bahrain, backed the assassination of the Kuwait emir, and otherwise sowed mayhem even when the chances of reaping revolution were low. Second, the new regime tried to delegitimize its rivals. For example, they accused the Saudi regime of practicing “American Islam” and otherwise criticized its religious credentials. Third, it managed to alienate both great powers at a time of intense superpower rivalry. The 1979-80 hostage crisis and Iranian-backed attacks by Hezbollah on the U.S. Embassy and Marine barracks in Lebanon in 1983 killed over 300 Americans and were, until 9/11, the deadliest terrorist attacks on Americans in U.S. history. Tehran, however, was also avowedly anti-Communist and believed the Soviet Union was supporting Marxist rebels in Iran itself.

This aggressive approach quickly led to a strategic backlash. Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein saw the new regime as militarily weak yet feared its ideological sway over his country’s Shiite majority, contributing to his decision to invade Iran. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and other states all rallied to Iraq’s side despite bearing no love for the bellicose Iraqi dictator because they feared Iran’s ideological power and revolutionary meddling. The United States too shifted firmly into the anti-Iran camp, imposing sanctions, aiding Iraq in its bitter war with Iran, and stopping arms sales to Tehran. (An exception to this was the Reagan administration’s covert provision of weapons in an attempt to free U.S. hostages in Lebanon in the Iran-contra program from 1985-1987.) Terrorism began to take on a more strategic logic, with Iran and its allies like the Lebanese Hezbollah attacking backers of Iraq like France and otherwise using terrorism to undermine its enemies.

The United States labeled Iran the world’s leading state-supporter of terrorism—a dubious status, but one it holds to this day. Tehran’s support for a range of militant groups continues, with Iranian leaders seeing them as a form of power projection and a way to undermine enemies as well as a way to help like-minded groups become stronger. Iran also uses these groups in conjunction with traditional insurgent warfare, above-ground political mobilization, and other means of increasing its influence. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and Iran’s intelligence service developed a range of connections to militant groups of many stripes and has recently used militants to great effect in Syria and Yemen. Its relationship with Hamas has also made Iran a player in the Israel-Palestine dispute. Iran’s zealotry may have diminished since the revolution, but its skill in using militants has steadily improved.

Even as Iran remains committed to working with militant groups, the broader nature of state sponsorship has evolved since the 1979 revolution. State sponsorship is still a danger beyond Iran, with countries like Pakistan arming, training, and funding an array of dangerous militant groups. Yet the ideological fervor that motivated Iran in 1979—and motivated Libya when Moammar Gadhafi took power in 1969 or Sudan in the mid-1990s—is now lacking among sponsors. Even states like Iran are more pragmatic and transactional, rather than seeing the world in black and white. With the rise of Sunni jihadist groups like al-Qaeda, that often had their own transnational funding and recruitment networks, “passive sponsorship”—when states knowingly turn a blind eye to terrorist activities on their soil—became more important and shifted the nature of the challenge.

The Iranian revolution and Tehran’s subsequent support for militant groups also created new regional dynamics that shape the Middle East and the nature of terrorism today. One of the most significant effectives was the religious mobilization of Saudi Arabia. Before the Islamic Revolution, Saudi Arabia’s religious establishment primarily looked inward and even saw many other Sunni Muslims as undeserving of aid because they were deviant (i.e. non-Salafi) Muslims whose faith was impure. The Iranian revolution, and the attacks on the regime’s legitimacy, led the Al Saud both to rely more on the religious establishment at home to shore up its credentials and to play up its support for Sunni Islam abroad. To undermine Iran’s influence, Saudi Arabia poured hundreds of billions of dollars into support for Salafism in Europe, the United States, Asia, and much of the Muslim world. In many countries, such funding supported radical mosques that became hubs for recruiting terrorists or led to much broader support for radical ideas that made it far easier for groups like the Islamic State to recruit.

The competition with Iran fostered a sectarian dynamic in the Middle East. After the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq and the rise of an Iran-aligned Shiite regime in Baghdad, clerics in Saudi Arabia began to play up the illegitimate nature of the regime there. This dynamic exploded when Syria slipped into civil war in 2011, with preachers in Saudi Arabia praising the resistance to the Assad regime because it opposed a deviant, Iran-backed regime. The war heightened sectarian tension and increased Iran’s regional influence with Riyadh then supporting anti-Iran forces in Lebanon and Yemen.

The Iranian revolution also led to profound changes in U.S. counterterrorism. The disastrous “Eagle Claw” hostage-rescue operation in 1980, which led to eight American deaths as a helicopter and a transport aircraft collided, led to the creation of special operations forces focused on hostage rescue and counterterrorism. The Joint Special Operations Command, which has emerged as a lethal terrorist-hunting machine in the post-9/11 era, emerged from this wreckage. In 1986, the CIA created its counterterrorism center, which after 9/11 became an intelligence behemoth.

Finally, for many Americans, the terrorism associated with the Iranian regime seemed to mark a new era in the very nature of terrorism. Religious inspiration, more than Marxism or nationalism, would mark this period. Iranian-backed groups like the Lebanese Hezbollah represented an early stage in this trend, but Hamas, al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and many like-minded movements would emerge as the most deadly type of terrorism violence facing the United States and its allies.

For the clerical regime in Iran, support for terrorism offered many tactical benefits, but it was often strategically self-defeating. Because Iran works with militant groups opposed to Sunni regimes and the United States, it cements its image as a rogue power, angers potential allies, and increases U.S. pressure on the regime—increasing Tehran’s dependence on militant groups and limiting its foreign policy options.