ISIS as Cult

Editor's Note: This is the final of four excerpts from the new book, ISIS: The State of Terror , by Jessica Stern and J.M. Berger.

, by Jessica Stern and J.M. Berger.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor's Note: This is the final of four excerpts from the new book, ISIS: The State of Terror , by Jessica Stern and J.M. Berger. In case you missed them, here are Part I, Part II, and Part III.

, by Jessica Stern and J.M. Berger. In case you missed them, here are Part I, Part II, and Part III.

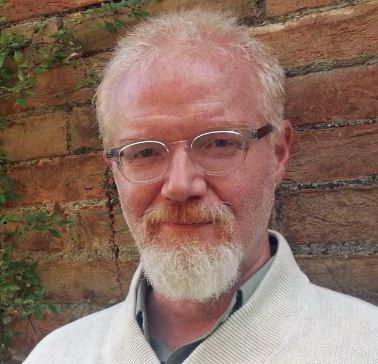

J.M. Berger is a fellow with George Washington University’s Program on Extremism. He is a researcher, analyst, and consultant, with a special focus on extremist activities in the U.S. and use of social media. Berger is co-author of the critically acclaimed ISIS: The State of Terror with Jessica Stern and author of Jihad Joe: Americans Who Go to War in the Name of Islam, the definitive history of the U.S. jihadist movement. He was previously a non-resident fellow with The Brookings Institution, Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World, and an associate fellow with the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation.