The Islamic State's "Homo Jihadus"

Editor's Note: It's hard to know what aspect of the Islamic State is most disturbing, but high on the list is the use of children as suicide bombers and executioners. Jacob Olidort of the Washington Institute draws on his study of Islamic State textbooks to explain how such practices are part of the Islamic State's broader indoctrination goals and why the United States and its allies should step up efforts to counter these.

***

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor's Note: It's hard to know what aspect of the Islamic State is most disturbing, but high on the list is the use of children as suicide bombers and executioners. Jacob Olidort of the Washington Institute draws on his study of Islamic State textbooks to explain how such practices are part of the Islamic State's broader indoctrination goals and why the United States and its allies should step up efforts to counter these.

***

ISIS’ August attack on a wedding party in Gaziantep in southern Turkey stood out from the group’s earlier attacks in that this one was committed by a child – sparking new interest in not only the group’s strategy, but what it teaches to children and recruits. Such teachings are integral to ISIS’ long-term objectives. I conducted a systematic review of the group’s official Arabic-language publications (157 titles), including roughly 100 textbooks for children, and found that ISIS has a new goal: creating homo jihadus.

Especially noteworthy among these textbooks, as I note in my report, is not only the ways in which the group indoctrinates children but also the lengths to which it goes to teach what we might call basic life skills and knowledge expected of children. These include topic such as handwriting, reading comprehension, basic mathematics and even physics and biology. In other words, subjects that we might expect to appear in the curricula of our own schools.

There are, of course differences – both visually and substantively. The authors of the textbooks never fail to miss an opportunity to insert some signature marker of the group, whether an ISIS flag at the end of a chapter on mathematics, an image of a gun, or the profile of an ISIS fighter. In their textbook on “The Sciences” – an elementary-level textbook dedicated to giving children a kind of blueprint of what the home and community look like, while teaching them basic vocabulary – a page with various members of the “ISIS home” has an image of a mother in a full-body covering and a father with a rifle.

There are also more sophisticated ways in which the group interweaves its homo jihadus goal into these subjects – and for its subtlety and sophistication, it is this approach that I see as the most enduring. Put differently, it is how ISIS provides basic skills and knowledge with the explicit aim of fighting on its behalf and building its capabilities – what I call in the paper “ISization” – as the feature that makes it both distinct from other jihadi groups and perhaps uniquely compelling for potential recruits. Examples of this include teaching computer programming in order to provide children with technological savvy to contribute to the group’s internet capabilities and teaching physical fitness with the aim of not only being healthy, but also fit to fight. This latter objective is the justification for additional chapters on assembling and firing weapons, as well as knowing what kind of ammunition can be used for different weapons. One could say, then, that the group’s recent encouragement of “weaponizing” everyday objects to terrorize on its behalf (as happened in the attack in Nice) is a reflection of this broader goal of homo jihadus – weaponizing every aspect of what it means to be a “citizen” of the Islamic State.

[T]he group’s recent encouragement of “weaponizing” everyday objects to terrorize on its behalf...is a reflection of this broader goal of homo jihadus – weaponizing every aspect of what it means to be a “citizen” of the Islamic State.

Although ISIS is notorious for its publications and propaganda extolling violence and the fundamentalist strain of Sunni Islam known as Salafism, it also gives equal attention to disseminating propaganda on more mundane and banal things, such as how to keep trim one’s beard and Arabic grammar – topics with no clear connection to anything violent. And in its school textbooks I have analyzed, ISIS teaches children topics such as geography and physics.

What are we to make of this odd literary enterprise?

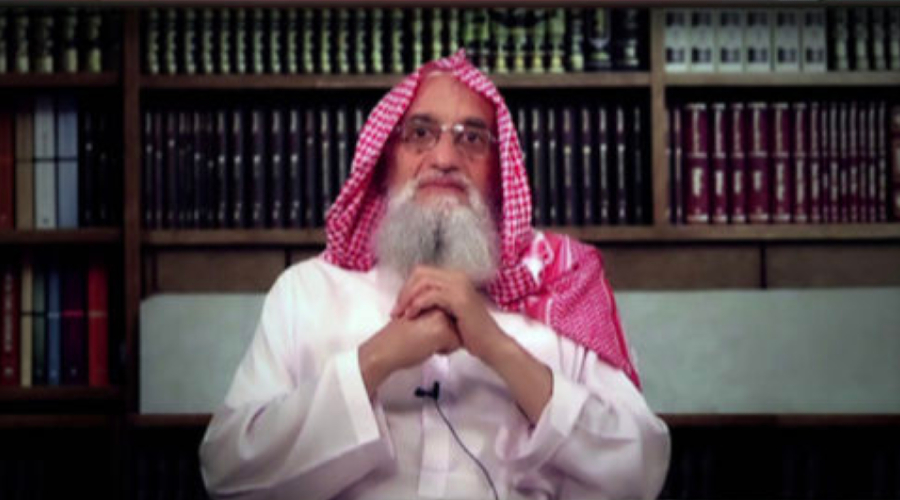

For one thing, publishing non-violent literature is not new among jihadists. Indeed, al-Qaeda head Ayman al-Zawahiri recently republished his edition of a medieval treatise on Arabic grammar. Scores of radical clerics on Twitter often opine on “softer” subjects, such as piety and religious practice.

Moreover, for some ISIS recruits this how-to-be-a-Muslim pedagogical program is a part of their attraction to the group. “While seeing someone die is not something anyone would probably want to see, having the actual Sharia established is what many Muslims look forward to,” said Abu Ibrahim, a defector speaking about why he joined ISIS. Similarly, recently leaked ISIS application forms reveal that many ISIS recruits lacked basic knowledge of Islam, filling their Amazon shopping carts with titles such as “Koran for Dummies.”

In contrast to other jihadist groups, however, ISIS’ non-violent messaging has a deep and direct connection to its recruitment successes. A core rallying cry is that it is the only territory on earth where a “pure” and original Islam is practiced and enforced. Enter ISIS propaganda on mundane and banal matters. Take for instance, ISIS stance against men grooming, ISIS sees this not only as a question of hygiene but also of civil obedience whose violation is grounds for punishment by ISIS.

In other words, ISIS aims to create an ideal Muslim homeland for the “ideal Muslim,” the homo jihadus. By extension, so the group’s narrative goes, anyone who fails to heed this call – to either migrate to Iraq and Syria or to fight on its behalf – is not a true Muslim.

ISIS aims to create an ideal Muslim homeland for the “ideal Muslim,” the homo jihadus.

And by calling itself a “caliphate” – a classical term in Islam that is restricted to religious and political leadership of Islam worldwide – the group rebrands Islam to justify its political endgame. To this end, ISIS had re-defined the Islamic religious obligation of migration (hijra) as not only requiring fleeing from a land of oppression, but also to territory controlled by ISIS. Unlike al-Qaeda, whose singular aim is to attack the West and its allies, ISIS provides for its audience an address for where they may live as true “jihadi citizens.” Even as the possibility of living in that state diminishes with the successes of the U.S. counter-ISIL campaign, the cause of being “Muslim” as ISIS defines it could endure. (For example, I recently wrote about how this “rebranding Islam” aspect could influence the nature of terrorist attacks).

Given this new understanding of the ISIS mission, what can the U.S. government and coalition forces do against ISIS?

While the fight in Iraq and Syria is indispensable for reducing the group’s military capabilities, it will do little to quash ISIS’s ability to inspire. Besides shifting strategy to offensive attacks, the group will continue to publish and disseminate material focusing increasingly on “Islam 101” rather than hard-hitting jihadist themes – especially as it seeks to reinforce group morale. So long as it can claim that it is the only true Islam around, ISIS will remain “inspirational,” with or without territory.

Identifying and working with moderate partners will continue to be integral to the combatting ISIS. Their work should go beyond “countering” ISIS’ messages, and these partners should be encouraged to codify alternatives. Creating lasting institutions, forums, and curricula in which Muslims can reclaim what ISIS has taken from them will be essential to defeating ISIS. In the end, the fight against extremism depends on controlling the spaces in which traditional Islam is being taught.

Besides the ideological part, there is another dimension that we have not yet fully appreciated – the food preparation that we need to do in Iraq and Syria while we take out the trash and mow the lawn. It is not enough to only fight ISIS on the territorial and messaging fronts, but we must also innovate ways of bringing education into these areas and maintaining cultural infrastructure. If left neglected, it is these two fronts of the ISIS project that will have more long-term effects that will be significantly more complicated to resolve down the road.