Is it Time to Regulate Cyber Conflicts?

In his keynote address at the RSA Conference on Feb. 14, 2017, Microsoft President Brad Smith described his vision for a more peaceful cyberspace.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

In his keynote address at the RSA Conference on Feb. 14, 2017, Microsoft President Brad Smith described his vision for a more peaceful cyberspace.

Smith articulated an arrangement in which governments would work together with private tech companies to tackle the growing threat of state-sponsored cyberattacks, as steady increases in the frequency, sophistication and cost demands it. Encouraged by positive indications in the international legal and diplomacy arena, Smith proposed a program based on three pillars.

First, governments—led by the American and Russian presidents—would agree to a “digital Geneva Convention,” forswearing cyberattacks on both the private sector and civilian infrastructure. Second, a new international regulatory agency would recruit experts from academia, industry and government to investigate and identify nation- states violating the convention—a sort of International Atomic Energy Agency for the cyber realm. Third, key tech companies would jointly assume a function like that of the Red Cross, playing “100 percent defense and zero percent offense,” protecting any state under attack and rejecting any government’s request to aid in attacking anyone.

states violating the convention—a sort of International Atomic Energy Agency for the cyber realm. Third, key tech companies would jointly assume a function like that of the Red Cross, playing “100 percent defense and zero percent offense,” protecting any state under attack and rejecting any government’s request to aid in attacking anyone.

I and others saw Smith’s proposal as a refreshing and encouraging sign of new thinking about how to make our new digital world safer.

More than a year later, Microsoft led 33 technology and cyber security companies, most in the U.S. to sign the Cybersecurity Tech Accord (CSTA), an agreement that harkens to Smith’s “digital Geneva Convention.” It includes four declarative principles:

- Protecting all customers everywhere;

- Opposing cyberattacks on innocent civilians and enterprises from any source;

- Empowering customers and developers to strengthen their cybersecurity protections;

- Partnering with each other and other like-minded entities to enhance cybersecurity.

Smith approves of the CSTA, describing it as “the first step in creating a safer internet,” which must come from “the enterprises that create and operate the world’s online technologies and infrastructure.” Still, some commentators have criticized the accord, focusing on what they see as the impracticalities of its principles and on the absence of Amazon, Apple, Google and other major tech companies, excluding Facebook, from the list of signatories.

Recent developments

Developments since the 2017 RSA conference do not paint an optimistic image.

Some of the positive signs that Smith identified in his speech have vanished. For example, the United Nation Group of Governmental Experts reached a dead-end in June 2017, failing to affirm the full application of international law, or at least its main principles, in cyberspace. Nevertheless, the Tallinn Manuals haven’t had yet a significant impact on state practice, as a new research paper surveying all major cyber operations conducted in the last five years shows (A Rule Book on The Shelf? Tallinn Manual 2.0 on Cyber Operations and Subsequent State Practice, by Dan Efrony and Yuval Shany - forthcoming).

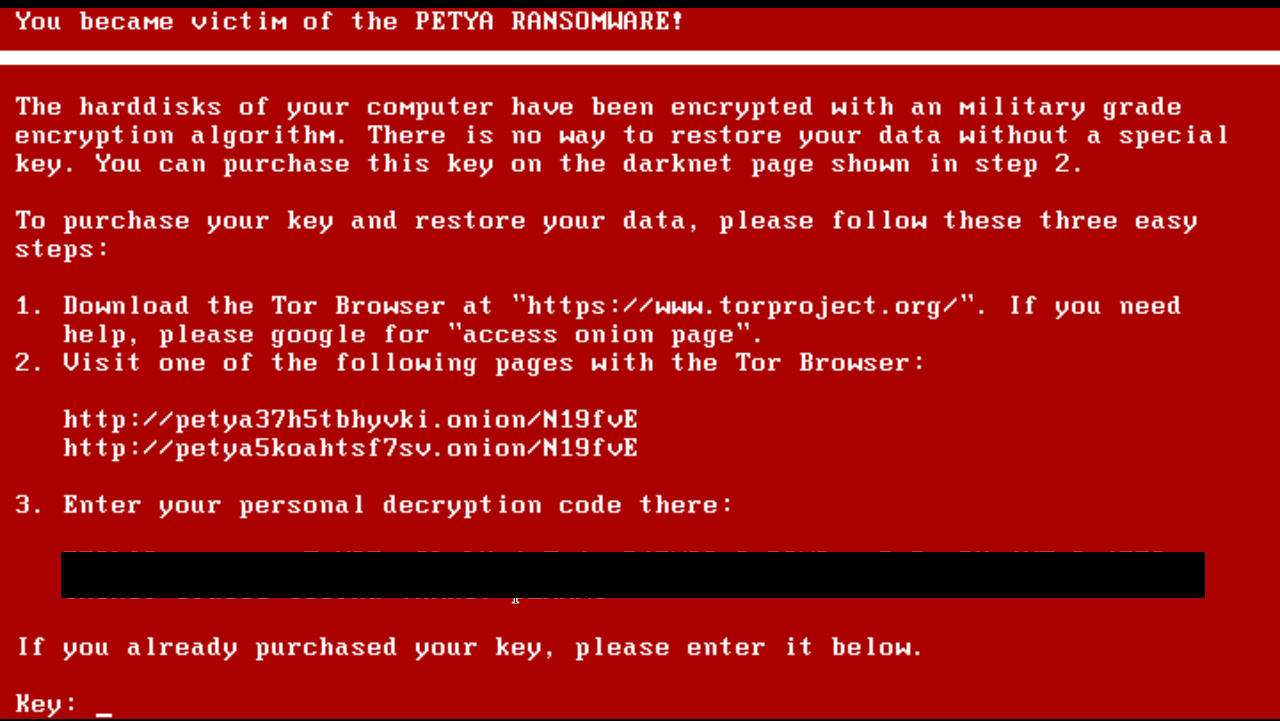

Furthermore, cyber attacks conducted or sponsored by nation-states haven’t stopped—or even slowed. To the contrary, the world has been rocked by unprecedented global cyberattacks, including the WannaCry attack, which hit computer systems in almost 150 countries simultaneously, and the NotPetya attack, which harmed civilian institutions and companies in 60 countries. Both attacks seem to have been executed by nation-states and caused enormous damages to civilian populations, corporations and institutions all over the globe.

On March 15, the New York Times reported on a failed August 2017 cyberattack against a Saudi petrochemical plant that investigators unanimously agree was “most likely intended to cause an explosion that would have killed people.” All that prevented the explosion, according to that reporting, was a bug in the attacker’s computer code. The incident was described as the first time in which a cyberattack intended to trigger a kinetic explosion. Apparently, it was the second: Between July and September 2016, a string of cyberattacks against oil and petrochemical facilities in Iran triggered fires and two explosions, killing one person and causing seven to be injured. Though there has been no formal attribution of those incidents by the victim nations (except a general accusation) the dominant professional assessment understands them as state-sponsored cyber operations. It certainly would not be a wild to imagine that Iran and Saudi Arabia might be the perpetrators, perhaps relying on the clandestine support of a more capable state.

Reveling in Ambiguity

The need for significant international initiatives to assure security and stability in the new digital world remains. Yet despite the limited success of the CSTA, no state has publicly expressed support or opposition to Smith’s idea—even those states that are very active in the field in using cyber capabilities to meet their national security needs and political interests. The lack of official stances is consistent with the ambiguity states typically embrace with respect to both legal doctrine and state practice in cyberspace.

States have a unique ability in cyberspace to accomplish their military, political or economic goals anonymously, with little risk of being held accountable and being required to pay a price for their actions. The same is also true for non-state actors and individuals, whatever their motives might be—though their cyber capabilities are usually much less sophisticated and dangerous than those of states.

The legal and political ambiguity coupled with the power to act covertly benefits the most technologically capable nations in cyberspace, and those nations won’t voluntarily give away their newly acquired strategic superiority. With the international community increasingly divided along political, ideological, and technological lines, the odds do not favor a legal breakthrough—neither through adopting Smith’s proposal, nor through resuming the Governmental Group of Experts process. It is thus likely that the U.N. secretary-general’s recent statement calling on the international community to finally regulate the field shall remain a voice crying in the wilderness.

A pessimistic outlook might be an accurate description of the current situation, which is often compared to the American Wild West. However, in my view, there is still a light in the end of the cyber tunnel—some hope for paving a new way, which, under certain conditions, could be more promising and practical than the launching of a new international convention.

A Shift Toward Retaliation

Western nations such as the U.S., U.K., France, Germany and others typically react with caution to cyberattacks conducted by suspected Russian, Chinese or Iranian culprits, as our research analyzing their recent responses shows. First, none of these states explicitly attributed attacks to Russia, China or Iran, even when the attack in question could have been attributed with a high degree of confidence. One exception is the Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. elections, which the U.S. did attribute and respond to, albeit hesitantly. Second, the U.S. adopted a name-and-shame by indicting the specific individuals involved in the attacks, in absentia, without acknowledging that their acts were committed in their capacity as state-agents.

A public speech by U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May on Nov. 14 of last year may be an early indication of a change in approach. May clearly pointed the finger at Russia, criticizing the Kremlin for orchestrating cyberattacks against Western countries as part of information or influence operations designed to undermine democracies and the international order. She warned Russian President Vladimir Putin: “We know what you are doing, and you will not succeed ... The UK will do what is necessary to protect ourselves, and work with our allies to do likewise.”

A month later, on Dec. 19, the U.S., U.K., Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Japan jointly attributed the WannaCry attack to North Korea. It was the first time a group of nations joined together to clearly assign responsibility to a specific nation and promising punitive measures would come.

Two months later, on Feb. 15, the U.S. announced that the Russian military launched NotPetya, and did so in order to destabilize Ukraine. The statement depicted the attack as “reckless and indiscriminate” and promised that it would be met “with international consequences.” The U.K. and Australia joined the U.S.’s attribution. A month later, the U.S. government imposed additional sanctions on Russian hackers and two Russian intelligence agencies involved in the 2016 election-interference operation, the NotPetya attack and additional intrusions targeting critical U.S. infrastructure. And just weeks ago, the U.S. imposed another round of sanctions on Russian oligarchs, senior Russian government officials, and Russian companies to retaliate for Russia’s interference in the 2016 election and other ongoing aggressions across the globe in Crimea, Ukraine and Syria. Those measures coincided with Britain’s prompt countermeasures against Russia for its use of chemical weapons directed against former Russian spy Sergei Skripal on British territory. In the aftermath of the Salisbury incident, more than 150 Russian diplomats have been expelled from 24 European countries, the U.S., Australia and Canada. This reflects a broad repudiation of Russia’s violations of international law and norms—presumably including, its role in cyberattacks.

Hopefully, after almost a decade of significant cyber incidents, each of them defined at the time as a “wake-up call” for the international community, someone finally woke up and started stretching his arms.

Moving Forward

These new developments are very important, but they must be married to a comprehensive long-term strategy.

In my opinion, Brad Smith’s vision is too ambitious. One premise should be set outright: In the foreseeable future, there is a negligible, not to say zero, chance to overcome the geopolitical, ideological, political, economic and technological gaps and conflicts that divide the international community. Therefore, barring a paradigm-shifting shock to the system, it is impractical to imagine a meaningful international convention that would apply to the permanent members of the U.N. Security Council, regulate their activities in cyberspace and curb their ability to engage in cyber warfare—be it a digital Geneva Convention, or something else. The policy recommendations elaborated below represent, in my opinion, a more realistic course of action toward reducing the intensity of cyber-conflicts and improving security on cyberspace.

Push back and be as transparent as possible

The first quarter of 2018 suggests that the major Western governments have understand that focusing primarily on defense in cyberspace is not enough; these nations need a more proactive, offensive approach under international law, such as attributing clear responsibility and undertaking countermeasures. After attribution is established, the evidence underlying it should be made as transparent as possible—restricted only by clear cut national security considerations. Attributing responsibility to a specific state with a high degree of transparency would help delegitimize abuses of cyberspace. It could also convince international public opinion, including other governments, to embrace more benevolent standards of conduct. Thus, when attribution is clear and transparent, countermeasures could and should be undertaken collectively by a group of convinced states (the bigger the group of states, the better) and as soon as possible.

Furthermore, releasing the evidence underlying attribution claims could open the door for additional deterrent measures, such as civil legal proceedings. In the case of NotPetya, for example, at least three multinational firms—Fedex, Maersk and Merck—and their insurance companies might sue Russia for causing direct damages totaling almost $1 billion.

International agreement is still available and needed

Of course, international law can also be shaped by the actions of small group of states. The EU and the Five Eyes members could generate standards about which values and principles are applicable to cyberspace and focus their efforts on enlarging the number of countries that share the same views. The negotiations among those countries should aim at formulating a new treaty based on what is lex ferenda (the law as it should be, to meet the new challenges of cyber capabilities) as opposed to regulation based on lex lata (the law as it is, based on the traditional international law).

Establish an accepted formula of attribution

One of the most important questions that should be addressed urgently, even if only through opinio juris, is the process for attributing responsibility. The evidentiary standards currently for attributing a cyber attack to a specific state remain open-ended. There is no consensus as to the legal and technological thresholds that need to be cleared to conclude whether the responsibility can be attributed to specific state. To date, only a few destructive cyber attacks have been clearly attributed to state “with high confidence.” In none of those cases did the nation to whom the attack was attributed accept the allegations and assume responsibility for the attacks. To the contrary, such states firmly denied any connection, instead calling on their accuser to disclose the evidence that the attribution was based on, rejecting the allegations for being politically biased, and at times, even demanding their participation in a common investigation committee.

Notably, the few attribution claims made explicitly with respect to incidents such as the Sony hack, attributed to North Korea, and the hack of the Democratic National Committee in 2016, attributed to Russia, have been subject to some disagreement even among American experts. In the case of the DNC hack, even the U.S. intelligence community expressed internal disagreement in its public report: whereas the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security made their joint assessment regarding Russia’s motives “with high confidence,” the NSA made its assessment only with “moderate confidence”.The question of attribution is connected to identifying how confidently certain technical parameters support the conclusion that a given actor conducted an attack. If attribution is based on accepted objective parameters and is transparent, other states would follow it, contributing to the establishment of state practice.

Establish an International Cyber Attribution Agency

Essential to analyzing technical parameters is the establishment of an International Cyber Attribution Agency (ICAA), an independent international agency like Brad Smith proposed. Such an agency would have the professional capacity to investigate and clearly attribute responsibility or to confirm the findings of another investigatory body. Every victim state could be eligible to invite this agency to independently investigate or join to ongoing investigation and publish its final conclusions. To increase trust in the agency, the agency should comprise of a variety of professional and academic experts (hailing from different countries and continents), and the selection should be strictly based on professional considerations. None of the experts should be simultaneously employed by governmental institutions to avoid even the appearance of conflicts of interest.

The leading companies in the private tech sector should voluntarily cooperate with the ICAA. Such cooperation both has social value will build customers’ confidence—surely a welcome development, given increased criticism faced by those companies overt failures to protect private and governmental data. And if the companies fail to cooperate, they might face new regulations sooner or later. If the new accord (CSTA) leads to the establishment of an international organization analogous to the Red Cross, then obviously that committee should embrace full and direct cooperation with the ICAA.

Some of the challenges that should be met in the process of establishing an attribution mechanism include setting a professional formula that includes the requisite, legal and technical, variables and the evidentiary standards to determine who is behind a given attack; and implementing appropriate transparency practices, including evidence and conclusions. If the process lasts more than three months, the agency should consider publishing intermediate findings and conclusions.

There is a serious deficit of trust among the leaders of the international community and a substantive reminder that it is easier to destroy than to build. The proactive approach presented above, if adopted and implemented, could help rebuild the trust among members of the world community and setting principles and norms to maintain international order, stability and security in our dynamic digital world.