It’s Time to Close Guantanamo

With the departure of U.S. and coalition forces from Afghanistan earlier this year, the United States ended the central front of its longest war. However, one relic from that war remains: The indefinite detention of presumed combatants at Guantanamo Bay.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

With the departure of U.S. and coalition forces from Afghanistan earlier this year, the United States ended the central front of its longest war—and one of its most costly in terms of lives and money.

However, one relic from that war remains: The indefinite detention of presumed combatants at Guantanamo Bay.

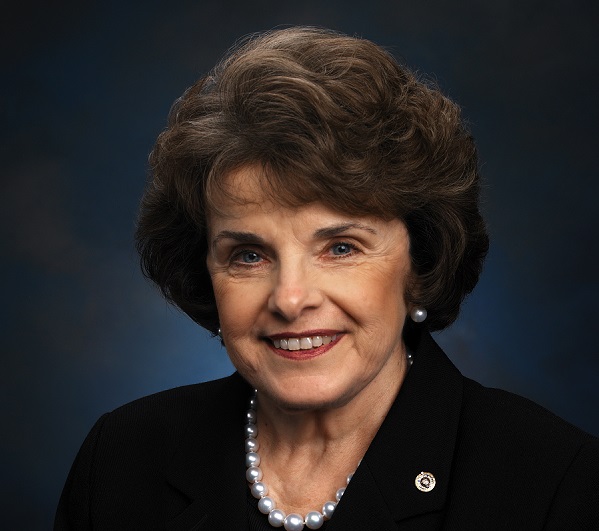

I’ve been to Guantanamo Bay Naval Base to see the detention operations twice—once in 2002 with then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and a congressional delegation and again in 2013 with Senator John McCain and then-White House Chief of Staff Denis McDonough.

After the latter visit, the three of us jointly wrote: “We continue to believe that it is in our national interest to end detention at Guantanamo, with a safe and orderly transition of the detainees to other locations.”

It was right then and it is even more true today: It is time for this last vestige of the war in Afghanistan to end.

Between January 2002 and March 2008, the United States brought 780 individuals to Guantanamo Bay. Many were senior al-Qaeda or Taliban members and leaders while others were cases of mistaken identity or individuals at the wrong place at the wrong time. Fewer than five percent were ever charged with crimes and the vast majority were ultimately released to their home countries or another nation.

By the end of his last term, President George W. Bush wanted to end detention operations at Guantanamo. He wrote in his memoir: “While I believe opening Guantanamo after 9/11 was necessary, the detention facility had become a propaganda tool for our enemies and a distraction for our allies. I worked to find a way to close the prison without compromising security.”

On his first day in office, President Obama signed Executive Order 13492 stating that the detention facilities “shall be closed as soon as practicable, and no later than 1 year from the date of this order.”

Nearly 13 years later, 39 of the 780 people brought to Gitmo remain, and no one has yet figured out a politically acceptable way to deal with them.

The cost to maintain this facility is $540 million per year—or about $14 million per detainee. That figure will only rise as the health care costs for this aging population increase. We need to resolve the fates of these 39 individuals and end detention at Guantanamo.

Of the 39 who remain at Guantanamo:

- Ten have been charged in the military commission process with war crimes and await trial.

- Two were convicted of terrorism-related charges and remain detained at the base.

- Twenty seven have never been charged. Of those, 13 have already been recommended for transfer out of Guantanamo under the long-standing interagency process established by executive order.

The Department of Defense should conduct a final status review for the 27 uncharged detainees. If there are grounds to bring charges after all this time in custody, they should do so. If not, detainees remaining uncharged should be sent home or to another country after appropriate security arrangements have been made.

Three things have stopped this from happening in the past: a concern that these individuals would pose a threat if released; the inability to transfer detainees to their countries of origin due to ongoing conflict or a lack of credible security or human rights assurances; and an unwillingness by other countries to accept their own citizens or foreign nationals.

The United States is much more secure today than it was on 9/11. We have vastly increased our homeland security capabilities and degraded the terrorist threat emanating from overseas. We can and should work with host countries to ensure returnees don’t pose a threat, as we have for more than 700 detainees already released from Guantanamo.

Regarding the concerns of host countries that don’t want their citizens back, perhaps the notion that the United States is finally closing Guantanamo as part of the deal would move them to act.

The 10 detainees who face charges are being tried by military commissions formed under the Military Commissions Act of 2006. Unfortunately, the military commission process has largely been a failure.

The biggest pending trial—a combined case against five detainees including 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and 9/11 facilitator Ramzi bin-al-Shibh—was filed in 2011. But a decade later, the actual trial hasn’t even begun. Delays have resulted from pre-trial motions, turnover in the presiding judge and government prosecutors, and challenges to the legality of the process.

And even if the trial begins, it’s far from clear how it would end. The recent case against Majid Khan is a cautionary tale.

Khan was charged with, among other things, delivering $50,000 to the group carrying out a terrorist bombing in Indonesia in 2003. He was transferred to Guantanamo from CIA custody in 2006.

Khan’s military commission trial earlier this year was the first time a detainee was allowed to describe in court his treatment at the hands of CIA interrogators. He spoke about being held naked, chained and in stress positions and being subjected to “rectal feeding.”

The military jury agreed to the minimum sentence in the case, but seven of the eight jurors wrote an extraordinary letter to the government urging clemency. They noted that Khan “has been held without the basic due process under the U.S. Constitution.” They called the CIA’s treatment of Khan “closer to torture performed by the most abusive regimes in modern history.”

Khan’s testimony made a strong impression on the jury. Why should we think the case against Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and others—many of whom faced even worse treatment while in CIA custody—would result in meaningful sentences?

Rather than risk prosecutions through a faulty military commissions process that could take many years with doubtful outcomes, the Defense Department and Justice Department should review past studies about trying charged Guantanamo detainees under our regular justice system. This has been done, albeit on rare occasions, over the past 20 years.

If convicted, detainees would spend their remaining time in federal prison. Those who are not convicted or are given sentences less than time already served should be sent to their home countries.

Likewise, the two Guantanamo detainees serving time can do so in U.S. prisons or overseas. Bringing detainees to the United States would require changes to U.S. law—which, to be clear, will be a tough task in today’s Congress.

Ending the failed experiment of detention at Guantanamo Bay won’t be easy. But now that the U.S.’s war in Afghanistan is over, it’s time to shut the doors on Guantanamo once and for all.

.jpg?sfvrsn=d5e57b75_5)