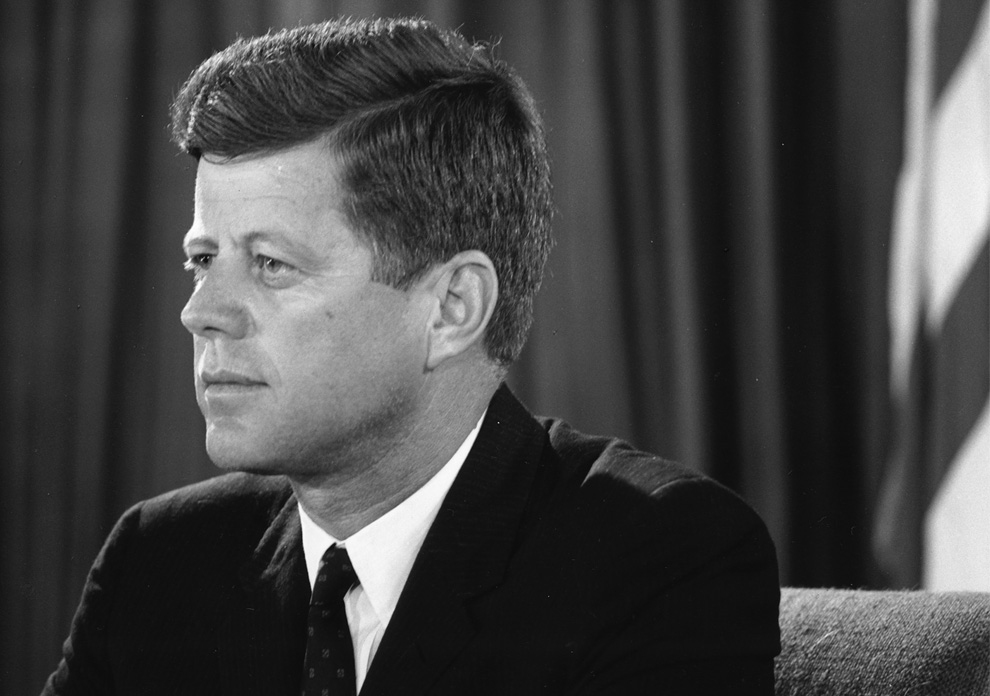

JFK’s Argument Against Imperialism

A review of Gregory D. Cleva, “John F. Kennedy’s 1957 Algeria Speech: The Politics of Anticolonialism in the Cold War Era” (Lexington, 2022).

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

A review of Gregory D. Cleva, “John F. Kennedy’s 1957 Algeria Speech: The Politics of Anticolonialism in the Cold War Era” (Lexington, 2022).

***

On July 2, 1957, Sen. John F. Kennedy gave an hour and fifteen minute speech to the Senate entitled “Imperialism: the Enemy of Freedom,” in which he called for a dramatic change in American foreign policy to support anti-colonialism in Africa and Asia even at the cost of damaging ties with key NATO allies like France, Portugal, and Belgium. It was Kennedy’s first big foreign policy speech, and it was critical of the policies of Presidents Truman and Eisenhower, who had supported France’s war to keep Algeria from independence. A new book, “John F. Kennedy’s 1957 Algeria Speech: The Politics of Anticolonialism in the Cold War Era” by Gregory Cleva, provides key insights into a pivotal moment in American diplomacy and politics, one with implications for the United States’ current challenges with NATO.

In 1957, half a million American-equipped French soldiers were bogged down in a violent campaign to repress 9 million Algerians seeking independence. Paris argued that Algeria was not a colony but an integral part of the French homeland. It had insisted that Algeria be recognized as France itself when it joined NATO, asserting that Article 5 applied to both France and Algeria. No other European ally asserted such a deal with any other colonial possession. One million of Algeria’s population were European settlers not native to the country, a key lobby against independence.

In the 1950s, Eisenhower’s foreign policy was dominated by his hard-line Cold Warrior Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who had a black-and-white view of the world. You were either an ally like France or a communist enemy. There was no place for neutrality or the Third World. The Algerians were supported by Dulles’s bete noire, Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser, the hero of Arab nationalism.

Kennedy rightly argued that this approach ignored the most powerful force in Africa and Asia: nationalism. The era of great European empires was rapidly coming to an end, Kennedy argued, and Washington needed to embrace the change and help the cause of independence. Algeria was the premier symbol of the anti-colonial struggle, and America was on the wrong side. Jack’s youngest brother Teddy had visited Algeria in June 1956, and his report of the trip had an important influence on JFK’s thinking about French North Africa. Kennedy was open to dialogue with Nasser and, later as president, engaged in an extensive exchange of letters with the Egyptian leader.

In the speech, Kennedy dismissed France’s legal argument that Algeria was a part of the French homeland like Normandy or Alsace, noting that, except for some French settlers, Algerians could not vote in French elections. Kennedy did not call for direct American intervention in Algeria but, rather, for mediation, perhaps by NATO or Morocco, to arrange an end to three years of violence and recognize Algeria’s “independent personality,” code word for independence.

The speech created a firestorm and resulted in more mail directed at Kennedy than any other issue in his senatorial career. The French government was outraged, as was the Eisenhower administration and most Republicans. The foreign policy establishment was negative: Former Secretary of State Dean Acheson said the speech was “naive.” Adlai Stevenson said that it was “terrible.” But it was applauded by liberals in the Democratic Party who had previously been suspicious of Kennedy’s foreign policy stance.

Of course Eisenhower and Dulles did not change policies. Instead, France came to grips with reality under the leadership of Charles de Gaulle, who accepted Algerian independence in 1962 despite several assassination attempts on his life and coup plots by fanatical generals. When JFK became president in 1961, he backed de Gaulle completely. France was the first European country Kennedy visited in office, and his glamorous (and French-speaking) wife, Jacqueline, took the country by storm.

Cleva’s book puts Kennedy’s speech in its historical and strategic perspective. In 1957, the United States had seven air bases in France and NATO was headquartered in Paris. The stakes were enormous for the U.S. But French and American policy was unsustainable; the French empire could not prevent Algerian independence indefinitely. Sen. Kennedy took a political risk and spoke out—a true profile in courage. In October 1962, Algeria’s new prime minister, Ahmed Ben Bella, visited Washington on his first foreign trip in a highly visible gesture of thanks for Kennedy’s support for independence; notably, the trip was in the midst of the Cuban missile crisis.

But Cleva also points out the shortcomings in Kennedy’s speech. He notes there was considerable hubris in the moralizing tone of the speech, a frequent flaw in Kennedy’s remarks. And JFK was slow to recognize that Cuba also was a revolutionary state in 1961-1962, driven far more by nationalism than communism.

Today, the United States confronts the last European empire, Russia, as it struggles to hold on to its prize possession, Ukraine. The NATO alliance has pulled together to arm the Ukrainians, who have demonstrated vividly that Ukraine is indeed a nation, despite Moscow’s claims that it is not. Like Kennedy in 1957, the U.S. needs to look for sustainable policy to prevent Russian aggression in its former orbit. Also needed are coherent speeches laying out in detail the logic of the U.S. position, and its limitations. As with the struggle for decolonization after World War II, this conflict is likely to be a long one, and resolve will be critical.