Jordanians See More to Worry About in Their Economy Than Syrian Refugees

Editor’s Note: Even as the Syrian war winds down, the millions of refugees it spawned show little sign of returning. Experts have long feared that these refugees will spread instability and, in poorer countries like Jordan, foster economic resentment. MIT’s Elizabeth Parker-Magyar finds that in Jordan such resentment is limited at best. The refugees remain welcome, and any economic resentment is directed at the government.

Daniel Byman

***

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: Even as the Syrian war winds down, the millions of refugees it spawned show little sign of returning. Experts have long feared that these refugees will spread instability and, in poorer countries like Jordan, foster economic resentment. MIT’s Elizabeth Parker-Magyar finds that in Jordan such resentment is limited at best. The refugees remain welcome, and any economic resentment is directed at the government.

Daniel Byman

***

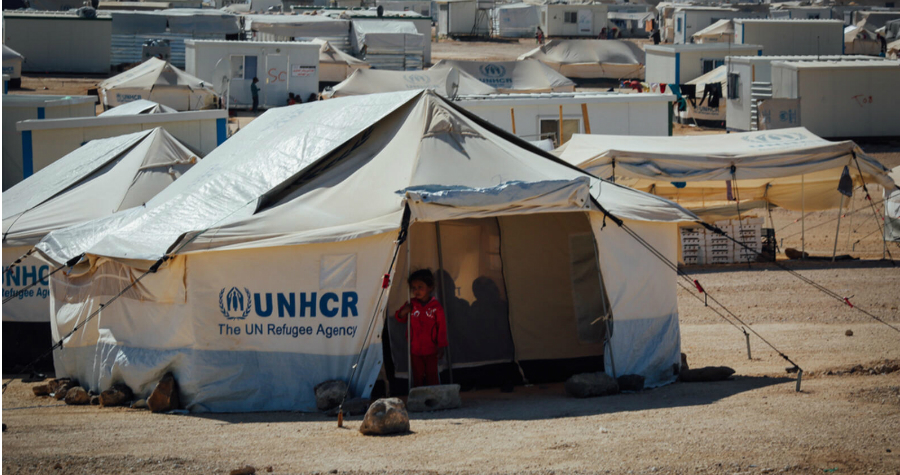

“I kept getting invited to meetings about the next ‘five-year plan’ for Za’atari. Are you kidding me? There is no way I’ll go,” a Jordanian aid worker and friend told me on a recent research trip, referring to the refugee camp that houses approximately 10 percent of the 662,000 U.N.-registered Syrian refugees in Jordan. “The camp should not be around for another five years. It is best for Syrians to go back to Syria, where they have some chance of building something.”

One year ago, the Syrian government recaptured the southern Syrian region that is home to the majority of Jordan’s Syrian refugees. In January, the Jordanian government reopened its border crossing with Syria. But Syrians in Jordan are in no rush to return to their home country, where returnees face continued violence and instability, a devastated economy, and—for young men—the risk of conscription. The most recent U.N. statistics show that just 3 percent of Syrians in Jordan have returned to Syria and just 8 percent of Syrians intend to return in the next year.

In the rest of the region, where individuals express similarly low intentions to return and where so-called self-organized returns occur at similar rates, many Syrians are not being presented with much of a choice. Politicians and street mobs in Lebanon and Turkey have increasingly scapegoated Syrian refugees for economic woes and political instability. In the past few months, Turkey and Lebanon have used legalistic pretexts to deport between hundreds and thousands of Syrians into active violence or into the hands of Syrian authorities. Just this week, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan told leaders of his party that he intends to send one million Syrians back to a proposed safe zone.

Such measures do not appear on the horizon in Jordan, which has exhibited relatively greater resilience to the economic and populist scapegoating of Syrians that has increasingly endangered their status in Turkey and Lebanon. In dozens of conversations in Jordan this summer, I heard well-worn narratives of cultural proximity to Syrian arrivals and government dependence on international aid as explanations for Jordanians’ refusal to scapegoat refugees. But far more than in previous visits, I heard a deep-seated solidarity with Syrian refugees borne from an increased preoccupation with domestic economic problems. In the wake of broad anti-government protests last year, many Jordanians I spoke with dismissed the blame placed on Syrians in Turkey and Lebanon as a distraction from deeper economic ills rooted in decades of neoliberal economic policy and economic mismanagement. This sets Jordan apart from other regional countries hosting Syrian refugees, but as the conflict winds down and international aid flows appear to decline, this welcoming environment may shift.

Cultural Proximity and “a Nation of Refugees”

The cultural and religious identity of Syrian refugees has clearly shaped Jordanians’ response. Like their Jordanian hosts, Syrians in Jordan are overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim. A 2018 survey highlighted the salience of this proximity, showing that Jordanians vastly preferred hosting Sunni Muslim Syrians to their Christian or Alawite counterparts.

Apart from religious ties, southern Syrians and northern Jordanians frequently share extended family ties and speak a roughly similar dialect. “I can speak in a Jordanian accent in a taxi, and no one can tell I am Syrian,” a Syrian friend told me. Interviewees highlight that these ties—and Syrian refugees’ relative poverty—stand in contrast to those of the hundreds of thousands of Iraqi refugees who are perceived to have driven up real estate prices while engaging in political advocacy from Jordan in the mid-2000s.

Unlike in Lebanon, then, narratives that the overwhelmingly Sunni Syrian refugee population threatens to destabilize a careful postwar sectarian balance among the nation’s Shiites, Sunnis, and Christians are unlikely to hold sway. In Turkey, too, demographic arguments increasingly portray Syrians, a handful of whom have gained citizenship and voting rights and who are also mostly Sunni, as a future voting bloc for Erdogan’s historically Islamist platform amid deeply polarized elections. The deportation of Syrians from Istanbul this summer follows Erdogan’s loss in a closely watched recount in the city’s mayoral election. These political and demographic arguments are less salient in Jordan’s monarchy, which features broader religious and cultural homogeneity and—despite increasingly vocal discontent—the absence of direct elections for the post of prime minister. Syrians in Jordan also have no path to gain citizenship, so there is no legal means by which they could exercise such political influence even if it was available to them.

Finally, Jordan’s lengthy history of hosting refugees—the majority of the nation is of Palestinian origin—and its status as a close U.S. ally dependent on foreign aid shape both the government’s strategy and the parameters of its response. While reliable figures on total aid from all sources are difficult to come by, Reuters reported in February of this year that Jordan had received $6 billion in international aid for the Syrian crisis since 2015. Including aid for foreign military funding and broader economic assistance, the United States has given Jordan $7.7 billion in assistance since 2015, making Jordan the “third largest recipient of annual U.S foreign aid globally, after Israel and Afghanistan,” according to the Congressional Research Service.

“The government needs to emphasize the needs of Syrians in order to raise money internationally,” Ammar Hamou, a Syrian journalist based in Amman, told me. More straightforwardly, Mohammad Momani, a prominent columnist and former government spokesperson, asked, “Why would Jordan want to ruin the beautiful international image it has created for itself” by deporting Syrians? The government has little incentive to encourage returns, and much to lose from the international backlash.

Domestic Economic Grievances in the Wake of Mass Protests

Beyond Jordan’s image as a welcome home for those fleeing the region’s violence, the Jordanians I spoke with repeatedly emphasized that any attempt to blame Syrians for their country’s economic woes is a distraction from more systemic issues. Indeed, Jordanians are acutely aware of the money that has come in for the Syrian crisis—and are keen to scrutinize the ways it has been spent. After a major protest movement last year led to the installation of yet another prime minister—Jordan’s seventh since 2011—many Jordanians now point to economic mismanagement and an over-reliance on international aid and International Monetary Fund (IMF) assistance, rather than the Syrian crisis, as the fundamental ill plaguing the country.

In my conversations with Jordanians, they expressed a palpable fear that international aid funding is drying up. But for many interviewees, the influx of Syrian refugees has been yet another opportunity for the government to fundraise internationally—and another instance in which international funding has bolstered international organizations and lined the pockets of well-connected individuals rather than generating sustainable, long-term economic resilience among either refugee or host communities.

One recent analysis published on a popular liberal website articulates the narrative relayed by many of the people I interviewed. The author, Taher al-Labadi, criticizes IMF-backed reforms in the Arab world and argues that they allow “[authoritarian and irresponsible] regimes to ensure control over economies that are ineffective due to corruption, nepotism and a waste of public money.” In Jordan, Labadi writes, regional wars and ongoing refugee crises “allow the country to gain foreign financing to maintain the degree of stability that allies of the Kingdom need.” The economic strain wrought by Syrians is the latest crisis allowing the government to justify economic underperformance and over-reliance on foreign donors whose prescriptions for economic liberalization have enriched some in the kingdom but devastated a middle class facing ever higher taxation and stagnant wages.

Hamou, the Syrian journalist, similarly emphasizes that economic concerns predate Syrian refugee arrivals—insulating them from blame by Jordanians frustrated by the economy. “Unlike in Turkey, which had a great economy, then Syrian refugees, then an economic crisis, Jordan’s economy has had numerous crises since well before the arrival of Syrians. As a result, Jordanians do not tie their economic problems to the arrival of Syrians.”

Finally, there is some evidence that Syrian refugees have helped, rather than hurt, the Jordanian economy. Multiple Jordanian interviewees, only somewhat tongue-in-cheek, emphasized that Syrians have raised the quality of the sweets in the country, bringing their skills to Jordan’s beleaguered restaurant industry. More substantively, a recent study of the Jordanian labor market shows that Syrians in Jordan’s workforce—many of whom are farmers, doormen, and construction or restaurant workers—compete more directly with Egyptian migrant laborers than Jordanians.

This is by design. Though Jordan has granted 138,000 work permits to Syrians as part of a 2016 trade agreement with the European Union, the nation still bars Syrians from more lucrative professions like medicine, engineering and law. “As a result,” Hamou tells me, “the Jordanians don’t have a problem with their government’s decision [to allow Syrians to work], but there is no economic future here [for Syrians], either.”

Fears of International Aid Drying Up

In my conversations, the deepest grievance I have heard stems from the perception that international donors have neglected other vulnerable populations, despite an agreement that aid to Jordan be split between Syrian refugees and their host communities.

These grievances are particularly salient among the nation’s longer term refugees from Palestine or smaller refugee populations like those from Iraq, Sudan and Yemen. “Syrians came [here to Jordan] just like us, 100 percent, and we empathize with them,” a mother of three from a Palestinian refugee camp north of Amman says. “But, as a Palestinian refugee, I wish I was a Syrian refugee,” she said, citing the dozens of Syrian families whose rent is subsidized by international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and who live in her neighborhood. “In Syria, Syrians are hardworking. Here, they are not—why would they be?” If foreign aid money dries up as Syria recedes from the headlines, these divisions could become more salient.

Moreover, Syrian refugees remain vulnerable as international and regional rapprochement with the Syrian regime in Damascus moves forward. “Any softening of the international donor community’s position [toward returns]” could allow the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees to limit the protections it provides to refugees in Jordan, a Jordan-based researcher for an international NGO tells me. The researcher scans the news for any official government policy that would legitimize deportations.

For now, though, possible refoulement of Syrian refugees from Jordan remains a more distant concern. With its history of welcoming migrations, with a government too concerned with international approbation and aid flows, and with a population highly attuned to and mobilized in favor of domestic economic reforms, the nation is unlikely to engage in mass scapegoating of Syrians anytime soon. Nevertheless, the situation in Turkey, where a Syrian contact told me the country “turned on the Syrians 180 degrees” overnight, is a reminder of how quickly things can change.