Judge McAfee: Don’t Lock Him Up

New terms for Harrison Floyd’s consent bond, and an answer to whether Gabriel Sterling enjoys being called a piece of fecal matter.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

It’s the Tuesday before Thanksgiving at the Lewis Slaton courthouse in Fulton County, Georgia, and one of the state’s top Republican officials, Gabriel Sterling, is on the witness stand. He’s been called to the stand by the district attorney, Fani Willis, to testify in a proceeding related to State of Georgia v. Donald J. Trump et al.

It's the first time Willis has personally appeared on behalf of the state since a Fulton County grand jury returned the sprawling racketeering indictment against Trump and 18 others in August.

It’s also the first time in the history of this great republic, at least as far as I’m aware, that testimony about the poop emoji has been elicited in a criminal case involving a former president.

“Do you enjoy being called a piece of fecal matter?” the district attorney asks the witness.

“No ma’am,” replies Sterling, the chief operating officer for the Georgia Secretary of State’s office.

I, for one, did not have “testimony about fecal matter” on my Trump Trials bingo card, but I guess that’s on me.

The reason the district attorney is asking about fecal matter on this Tuesday afternoon has something to do with the man in the bright green jacket who is seated at the defense table to my right. That gentleman is none other than Harrison Floyd, one of Trump’s co-defendants in Fulton County.

Floyd, the former leader of a group called Black Voices for Trump, has been charged alongside Trump for participating in an alleged criminal enterprise to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. Floyd also faces two separate felony charges related to an alleged campaign to intimidate Ruby Freeman, a Fulton County elections worker, and pressure her to falsely state that she had committed election fraud.

Following his indictment in Georgia, Floyd was briefly incarcerated at the Rice Street facility, an infamous Fulton County jail. But by the end of August, he had agreed to the terms of a “consent bond,” which set out several conditions of his release from jail. Pursuant to that consent bond, Floyd is prohibited from intimidating “any person known to be a witness in this case.” He must also refrain from communicating “in any way, directly or indirectly” about the facts of the case with any person known to him to be a witness or a codefendant.

In a motion filed last week, Fulton County prosecutors argued that Floyd

engaged in numerous “intentional and flagrant” violations of his conditions of release and should be sent back to jail.

I suspect that’s why, earlier this afternoon, the typically animated Floyd appeared unusually subdued as a court officer shouted “All rise!” and Judge Scott McAfee, the 34-year-old wunderkind who holds Floyd’s freedom in his hands, took a seat behind the bench. Following brief opening remarks from both the prosecution and the defense, Willis called her first witness to the stand: Michael Hill, an investigator for the district attorney’s office.

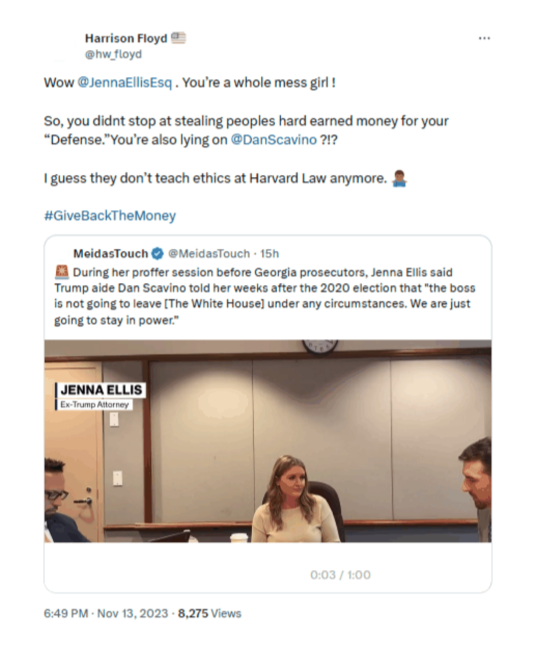

On direct examination, Hill elaborated on the evidence cited by prosecutors as grounds to revoke Floyd’s bond: A series of social media posts on Twitter, now called X, in which Floyd allegedly intimidated potential witnesses or communicated with co-defendants or witnesses. In one such post, Hill explained, Floyd “tagged” his former co-defendant Jenna Ellis, who recently struck a negotiated plea deal and agreed to cooperate with prosecutors. Floyd’s post called Ellis a “whole mess” and accused her of “lying” in a proffer video she recorded as a condition of her plea. Hill said he reached out to Ellis about the post, who replied that she felt it was “meant to intimidate and harass me.”

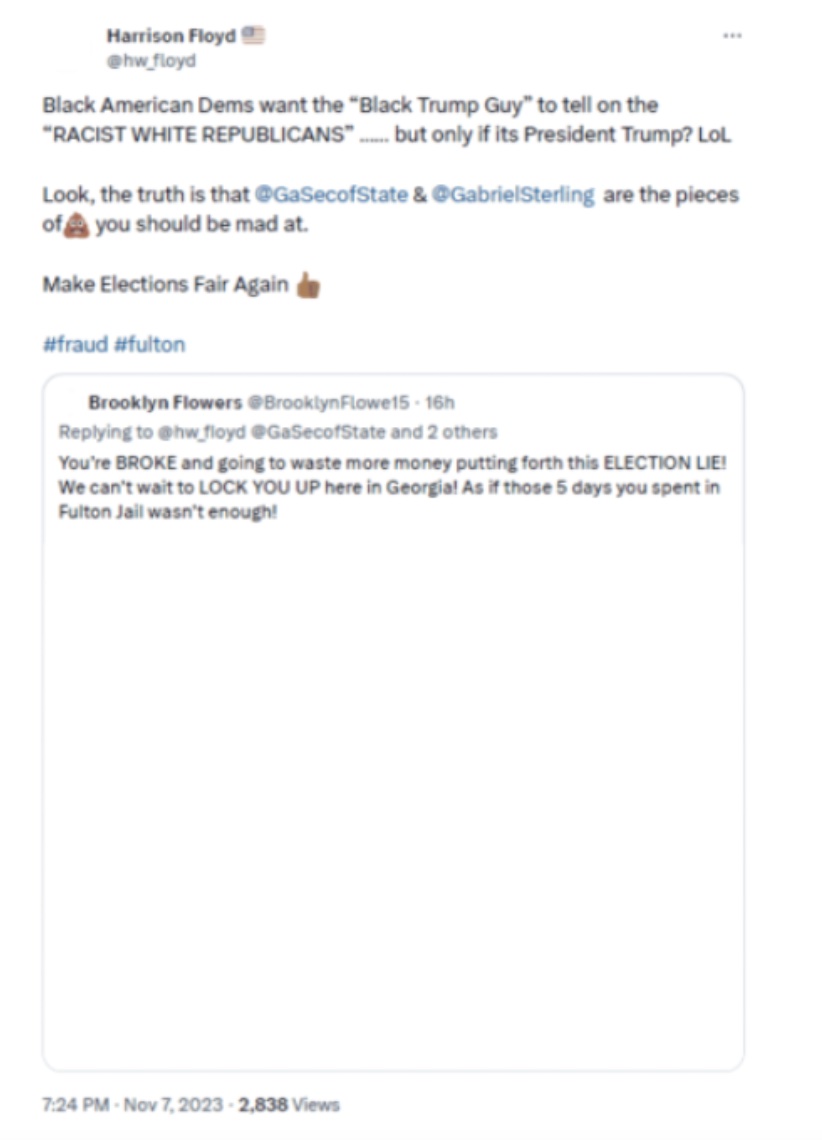

Hill then described other posts by Floyd, several of which involved statements about Freeman, the elections worker who was the subject of the alleged pressure campaign carried out by Floyd and others in the wake of the 2020 election. Finally, Hill turned to Floyd’s posts about Brad Raffensperger, the Georgia Secretary of State, and Sterling, his chief operating officer. In one of the posts, Hill said, Floyd called Raffensperger and Sterling “pieces of 💩.”

All of which brought us to the present moment, in which Willis, having called the state’s second witness of the day, asks Sterling if he enjoys being called a piece of 💩. Sterling responds in the negative.

Moving on, Willis briefly asks Sterling to confirm that he is a witness in the case and that he saw the posts Floyd tagged him in. Sterling replies in the affirmative.

After a brief cross examination of Sterling by Floyd’s defense counsel, the state calls its third and final witness of the day: Van Dubose, an attorney for Freeman. Dubose, clad in a charcoal gray suit, explains that he hired a firm to conduct social media threat assessments for Freeman and her daughter, Shaye Moss, who are both presumptive witnesses in the case. In the wake of the 2020 election, Dubose explains, Freeman became the subject of so many threats that she was forced to leave her home at the recommendation of the FBI.

According to Dubose, a recent threat assessment report showed a “spike” in online activity concerning Freeman after Floyd posted comments about her on X. That uptick in activity necessitated the implementation of extra safety measures for Freeman and Moss, Dubose says.

Floyd’s counsel, Chris Kachouroff, jumps up for cross examination. Focusing first on the threat assessment report, Kachouroff elicits testimony from Dubose in which he concedes that the report did not exclusively analyze the impact of Floyd’s posts about Freeman. Then Kachouroff asks Dubose if any of the posts would constitute a threat under Georgia law. “There’s nothing in those posts that’s intimidating to a reasonable person, is there?” Kachouroff inquires. Dubose, in reply, says he disagrees.

Now, after nearly two hours of witness testimony, Judge McAfee is ready to hear closing arguments.

Kachouroff is up first on behalf of Floyd. To start, he addresses the state’s argument that Floyd’s posts constitute “intimidation” or “harassment” of witnesses. None of these posts, Kachouroff claims, would put a reasonable person in fear for his or her safety. As such, he continues, the posts do not violate the terms of Floyd’s consent bond.

Next, Kachouroff turns to the state’s claim that the posts amount to “communication” with co-defendants or witnesses. But “tagging” a person in a post on social media does not constitute communication, Kachouroff contends.

Moving to the equities at issue, Kachouroff reminds Judge McAfee that Floyd traveled to Georgia from his home in Maryland today because the court told him to. If the court tells Floyd to tone down his rhetoric, he will, Kachouroff promises. And if the court offers a choice between freedom of speech and his personal liberty, Floyd will choose his liberty. For that reason, Kachouroff urges, the appropriate resolution here involves amending Floyd’s condition of release, not sending him to jail.

As Kachouroff returns to his seat at the defense table, Willis rises to her feet to deliver a closing argument on behalf of the state. Before she begins, however, she announces that her closing argument will be accompanied by a PowerPoint presentation.

After a brief pause as Willis loads the PowerPoint slides, she starts by reminding Judge McAfee that the standard of proof is preponderance of evidence, meaning that the state need only show that it is more likely than not that Floyd violated his conditions of release and that his bond should be revoked.

Turning to the substance of the state’s arguments, Willis observes that Floyd voluntarily agreed to restrictions on his speech when he signed the consent bond in August. What’s more, she continues, Floyd knew that Ellis, Sterling, and Freeman were witnesses in the case. Freeman, for example, is mentioned more than 40 times in the indictment, Willis says. At this, she flips to a new slide: “The Absurdity of the Defendant’s Argument.”

Willis tells McAfee that there are real consequences for allowing defendants to intimidate witnesses. And the trial court has a duty to keep witnesses safe, she reminds McAfee. For those reasons, she says in closing, the state asks that the court revoke Floyd’s bond.

McAfee, who at this point seems ready to call it a day, says he will gather his thoughts for a few minutes in chambers.

When he returns, McAfee observes that, while Floyd’s posts may have pushed the limits of what might constitute witness intimidation, the key question at issue here is whether Floyd’s social media posts amount to indirect “communication” with witnesses. And in that regard, McAfee announces, the court finds that there has been a “technical” violation of Floyd’s bond conditions.

Still, Judge McAfee continues, “not every violation compels revocation.” In these circumstances, he thinks the most appropriate solution involves amending Floyd’s conditions of release, not by remanding him to custody.

Judge McAfee orders the parties to take a brief recess to draft proposals for the new terms of Floyd’s consent bond. Later, as the parties discuss the provisions in the state’s proposed order, Willis refers to “defendant Trump.” Floyd pipes up: “President Trump,” he emphasizes.

Judge McAfee, in reply, issues a warning: Mr. Floyd, it’s not your turn to speak.