Khalid Batarfi and the Future of AQAP

The new leader of al-Qaeda's Yemen-based franchise inherits a weakened organization.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), long considered one of al-Qaeda's most dangerous and capable affiliates, is under new management. Gregory Johnsen, one of the world's premier Yemen analysts, assesses the state of AQAP today and argues that its new leader inherits a far weaker organization that will struggle to stay relevant.

Daniel Byman

***

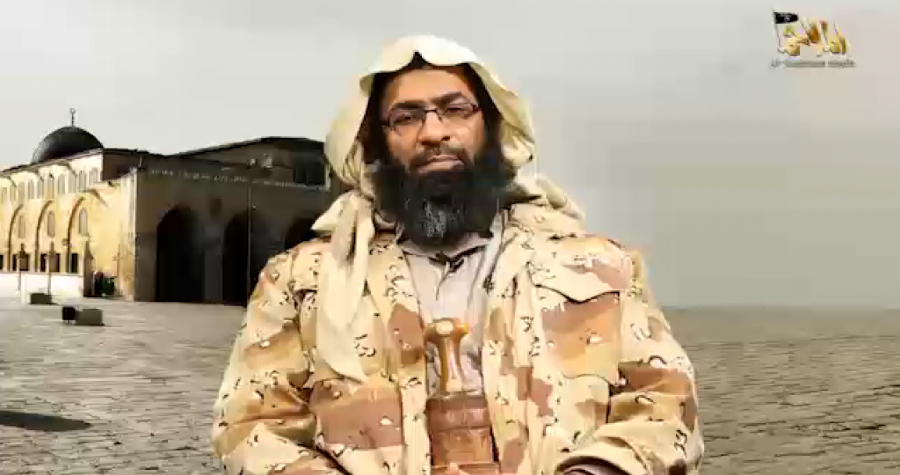

On Sunday, Feb. 23, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) announced that it had selected Khalid bin Umar Batarfi as the group’s new leader. Batarfi—who is also known as Abu Miqdad al-Kindi, a nod to his family’s Hadhrami roots—is AQAP’s third leader since the group was formed in January 2009. AQAP’s first two leaders, Nasir al-Wuhayshi and Qasim al-Raymi, were both killed in U.S. drone strikes: Wuhayshi in June 2015 and Raymi in Jan. 2020.

Batarfi’s selection checks two important boxes for AQAP. First, he is from the Arabian Peninsula, as was the case with both of the group’s former leaders. Wuhayshi and Raymi were each born in Yemen; Batarfi is from a Yemeni family but was born in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, in 1979. (The U.S. Department of Treasury’s specially designated nationals listing also gives 1978 and 1980 as possible dates of birth.) Second, Batarfi has extensive international jihadi credentials. He trained and fought in Afghanistan prior to September 2001, assisted fighters traveling to Iraq following the U.S. invasion in 2003, and helped lead AQAP’s push to seize territory in southern Yemen in 2010 and 2011.

Other possible candidates, such as Ibrahim al-Banna, Ibrahim al-Qosi and Sa’ad bin Atef al-Awlaki, all checked one box or the other, but not both. Banna and Qosi are both foreigners, from Egypt and Sudan, respectively. Awlaki is the head of AQAP in Shabwa, where he has strong local ties, but is less well known internationally.

Still, it is unclear exactly how much support Batarfi enjoys within the organization. The succession announcement made clear that while AQAP attempted to consult with as many of the group’s top commanders as possible, the operating environment in Yemen meant that not everyone was consulted. AQAP’s top leaders rarely communicate electronically for fear that the United States will be able to turn intercepts into targeting coordinates. Instead they often rely on personal couriers to transmit messages, which can take days to reach the intended recipient, particularly if the courier has to cross one of Yemen’s various frontlines. Order-by-courier is possible, consultation and discussion-by-courier is not. This is one of the (many) reasons that decision-making within the group has devolved in recent years, exacerbating the group’s fragmentation into local or regional nodes.

It is also unclear whether the other three potential candidates to succeed Raymi will fall into line behind Batarfi and offer him their oath of allegiance. Even before Raymi’s death, sources in Shabwa were speaking openly about the possibility of Awlaki supplanting Raymi as the head of AQAP. Whether or not Batarfi can gain their support will go a long way toward determining AQAP’s future.

Batarfi’s Background

Although he was born in Riyadh, Batarfi graduated high school in Jeddah, eventually studying with a number of prominent Salafi shaykhs in Saudi Arabia before leaving for Afghanistan in 1999. He spent eight months in the country, training at al-Qaeda’s Farouq Camp near Kandahar and fighting alongside the Taliban. According to a detailed biographical sketch, which he provided to the editor of al-Mukalla al-Youm in 2015, Batarfi returned to Afghanistan months before 9/11. He fought with al-Qaeda before slipping across the border to Pakistan and eventually to Iran. Like Nasir al-Wuhayshi, Batarfi was imprisoned in Iran for a short time before being sent to Yemen. Then-Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh held Batarfi in prison for two years before releasing him in 2004.

Between 2004 and 2008, Batarfi maintained a low profile. Al-Qaeda didn’t have much of a presence in Yemen in 2004 or 2005, and Batarfi spent much of his time providing support for Yemenis traveling to Iraq to fight. Batarfi also married a local Yemeni woman during this period and had two sons, Abd al-Rahman and Abdullah. The younger, Abdullah, would later die while Batarfi was in prison in al-Mukalla.

In 2008, Batarfi rejoined al-Qaeda’s recently resurrected affiliate in Yemen. Two years later, in 2010, he led AQAP’s push into Abyan and was later named the group’s emir in that governorate. However, in March 2011, he was arrested at a checkpoint outside of Taiz on a visit to his family. Initially, he was sent to prison in Sanaa, but in late 2013 Batarfi was transferred to the Central Security Prison in al-Mukalla. During the 19 months Batarfi was imprisoned in al-Mukalla, Yemen changed dramatically. The Houthis, a Zaydi-Shiite movement, took control of Sanaa in September 2014, placing Yemen’s president, Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, under house arrest until he eventually escaped into exile in Saudi Arabia. In March 2015, Saudi Arabia launched Operation Decisive Storm, which was aimed at expelling the Houthis from Sanaa and restoring Hadi to power.

AQAP took advantage of the chaos and fighting across Yemen to launch an offensive on al-Mukalla a month later, in April 2015. As part of this offensive, AQAP took control of the local prison, freeing Batarfi and more than 200 other inmates. Reveling in his newfound freedom, Batarfi stopped for a photo op at the presidential palace in al-Mukalla. One picture shows him standing on the Yemeni flag, another features the heavyset Batarfi lounging on a gold sofa, rifle in one hand, telephone in the other.

Barely two months after AQAP took control of al-Mukalla and freed Batarfi, the head of the organization, Wuhayshi, was killed in a U.S. drone strike. Wuhayshi was replaced by his longtime deputy, Raymi, while Batarfi slowly emerged as one of AQAP’s preeminent ideologues, commenting on everything from the Pope’s visit to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in February 2019 to the persecution of Muslims in Myanmar.

AQAP’s Future

The AQAP that Batarfi inherits in 2020 is significantly different from the one Raymi took command of in 2015. AQAP is weaker, more fragmented and less able to conduct international attacks than at any point in its 11-year history. It is also almost entirely a domestic organization. Over the past five years, AQAP has gone from being one of the most dangerous al-Qaeda affiliates to becoming a shadow of its former self. AQAP still threatens attacks, but it no longer has the resources or capacity to carry them out on a consistent basis.

This is partly a result of the Islamic State’s rise in Syria and Iraq, which in recent years has been the destination of choice for would-be international jihadis. Recruits who in 2011 or 2012 might have self-selected to travel to Yemen were, by 2014 and 2015, making their way to Syria. That shortfall is now limiting AQAP’s ability to project strength from Yemen. Another part of the equation is that AQAP has lost a number of key figures in drone strikes and, due to the recruiting shortfalls, has been unable to replace them. In addition to Wuhayshi and Raymi, the United States has killed figures such as Anwar al-Awlaki and Ibrahim al-Asiri, who was responsible for many of the group’s most sophisticated bombs.

AQAP can still recruit local Yemenis into its ranks, but it no longer attracts the sort of skilled foreign operatives it needs to threaten the West. That drop-off has been matched by a sharp decline in the number of international attacks claimed by AQAP. Since 2015, AQAP has been linked to only two attacks outside of Yemen: the January 2015 attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris and the December 2019 shooting at the naval base in Pensacola, Florida. But even these ties are tenuous. In an audio message, recorded before he was killed but released afterward, Raymi took credit for the Pensacola attack. However, Raymi’s claim is backed up with little evidence and the shooting in Florida appears to be more an inspired attack than a directed one.

In much the same way that AQAP’s international terrorist wing atrophied under Raymi’s leadership, so too has its domestic insurgent wing struggled. The group has been infiltrated by spies and informants—Raymi was reportedly killed after an informant gave his location to the CIA—and over the past two years AQAP has been involved in a tit-for-tat war with the local Islamic State affiliate that has occupied much of its attention and most of its resources. As with many of the combatants in Yemen’s overlapping wars, AQAP is fighting multiple enemies on multiple fronts: the Houthis, the Southern Transitional Council and its associated UAE-proxy forces, the Yemeni government, and the Saudi-led coalition.

Batarfi’s two main priorities will be to revive an organization that has fallen into disarray while simultaneously attempting to revitalize its international operations. Neither will be easy to accomplish. Earlier this year, the U.N.’s 1267 committee, which monitors al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, reported that following the death of Asiri in 2017, Batarfi had already taken responsibility for AQAP’s external operations.

AQAP is on the verge of defeat for the first time since the group was founded in 2009. Should Batarfi’s time in charge prove short, or should he turn out to be an ineffective leader in the mold of Raymi, AQAP will most likely fragment into regional pieces that are more criminal than terrorist. However, if he is given time and space to rebuild the organization, AQAP could once again emerge as an international threat.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the location of an attack that occurred in January 2019. The attack occurred in Pensacola, Florida, not Sarasota.