Law and Lawfare in the Islamic State

Last month, the Islamic State’s official media outlet, al-Furqān, released its first video in over a year, entitled, “The Structure of the Khilafah.” Al-Furqān is known for producing the group’s most horrific propaganda, including infamous footage showing the torture and execution of journalists, aid workers, and POWs, so it is noteworthy that the latest video features relatively little violence.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Last month, the Islamic State’s official media outlet, al-Furqān, released its first video in over a year, entitled, “The Structure of the Khilafah.” Al-Furqān is known for producing the group’s most horrific propaganda, including infamous footage showing the torture and execution of journalists, aid workers, and POWs, so it is noteworthy that the latest video features relatively little violence. What violence there is, which appears in the form of some gruesome battle scenes and enemy casualties, is relegated to the final minute of the film.

“The Structure of the Khilafah” purports to illuminate the inner workings of the Islamic State’s bureaucracy. Through a series of organizational charts and infographics, viewers are taken on a tour of the many offices, councils, and commissions that the Islamic State uses to govern its so-called “caliphate.” Considerable time is devoted to tedious explanations of administrative techniques like delegation and decentralization. At one point, the narrator explains: “The task of communicating orders once they have been issued and ensuring their execution is delegated to a select group of knowledgeable upright individuals with perception and leadership skills as the caliph [an office currently held by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi] cannot himself personally carry out all the work of the state, for that is an impossible endeavor, so it is necessary for there to be a body of individuals that supports him.”

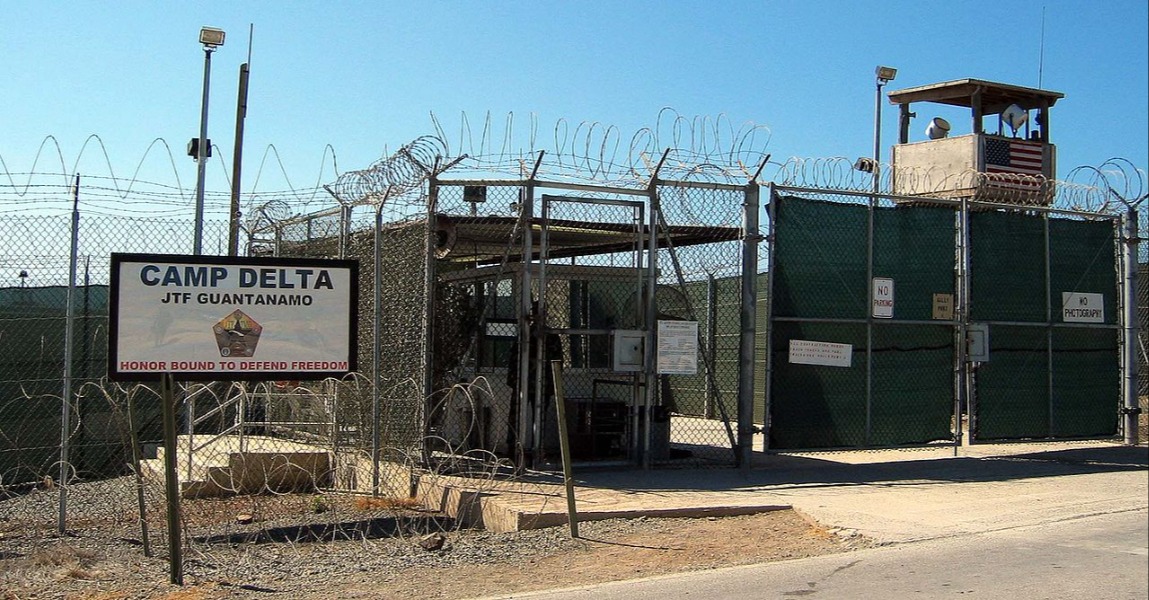

Image: This organizational chart, one of many presented in the latest Islamic State video, illustrates--from left to right--(1) the caliphate’s administrative committees, (2) its 35 “wilayaat” (administrative divisions analogous to provinces); and (3) 14 functional offices responsible for healthcare, taxation, education, agriculture, and military affairs, among other matters.

This is the latest in a series of communications—including al-Furqān’s last video in 2015, which showcased a taxation and welfare system known as zakāt—that appear to be aimed at convincing the group’s supporters, as well as its enemies, that the caliphate is still a fully functioning state, despite recent military setbacks and territorial losses in Iraq and Syria.

The Islamic State was once dismissed by skeptics who predicted that the group would never amount to anything more than a “paper state.” In the two years since al-Baghdadi announced the establishment of a caliphate in June 2014, the group has been trying to prove those skeptics wrong. Claiming sovereignty over tens of thousands of square miles of territory and millions of people, the Islamic State sees itself as building a new political and religious community according to the model first laid out by the Prophet Muhammad in the seventh century. As evidenced by its latest video, the group measures its success not only by cities captured and enemies killed, but by the growth of a bureaucracy that is capable of lawmaking and governance.

How has the Islamic State built this bureaucracy? In a recent paper for Brookings based on interviews with 82 Syrians and Iraqis from areas governed by the Islamic State, I argue that the group’s radical state-building project rests on legal foundations. Most accounts of the Islamic State’s seemingly archaic legal system tend to fixate on the grotesque punishments it administers—including decapitations, stonings, and immolations—without considering the broader role that the system plays in advancing the caliphate’s economic, military, and social objectives. In fact, the Islamic State has weaponized law as a tool for state-building. Arguably, it is engaged in “lawfare.”

Historians and political scientists have long recognized that legal institutions greatly facilitate the formation of modern states by legitimizing violence, protecting economic transactions and property rights, and justifying taxation and military conscription. If we take seriously the “state” in “Islamic State,” then we should also take seriously the institutional building blocks of that state, including its legal system.

Like all legal systems, the Islamic State’s has (1) rules—based on the divinely revealed body of Islamic law known as shari‘a—(2) a judiciary to apply them, and (3) a law enforcement apparatus to ensure compliance. The Islamic State appears to be using this legal system to advance at least three different state-building objectives: (1) establishing a legal basis for territorial sovereignty and expansion; (2) enforcing internal discipline within the Islamic State’s own ranks; and (3) justifying taxation, which has become an increasingly important source of revenue for the group.

1. Territorial Sovereignty and Expansion

Legal institutions have made it easier for the Islamic State to capture and retain territory by legitimizing its claim to sovereignty and building goodwill with civilians. First, the Islamic State purports to be reclaiming lands that were unlawfully taken from Muslims by Western occupiers. The group has generated a vast amount of propaganda proclaiming “the end” of the Sykes-Picot order, including one well-known video in which bulldozers literally demolish the border between Iraq and Syria. In order to destroy an existing world order, the Islamic State must assert an alternative legal framework to fill the vacuum. It has done this by claiming that the caliphate is the only legitimate government on earth. According to the Islamic State, true Muslims have a divine obligation to live within its borders.

Second, the Islamic State uses its legal system to build goodwill with communities that are desperate for order and security. Like any insurgent group, the Islamic State depends on the cooperation of civilians to capture and control new territory. One way to earn their trust (and fear) is by solving local problems and punishing troublemakers. Conflict creates opportunities for looting, land grabs, and crime. The Islamic State’s aggressive prosecution of criminals and rapid resolution of disputes in previously lawless areas is often welcomed by civilians, at least initially. One Syrian from Aleppo told me that the crime rate in his city had fallen to “near zero” since the arrival of the Islamic State. “You can leave a cell phone on a table in a café, and it will still be there in a week, because everyone is afraid of the consequences of stealing.” Another reported that his cousin joined the Islamic State after he was impressed by its speedy resolution of a land dispute for his aunt.

Such examples suggest that courts facilitate the Islamic State’s territorial expansion both directly—by establishing its legal authority over previously contested lands—as well as indirectly—by winning hearts and minds.

2. Internal Control and Discipline

No government can establish itself as legitimate without policing the behavior of the people who are responsible for implementing its policies. Indeed, failure to punish corruption is among the primary causes of dissatisfaction with the current governments of Iraq and Syria. By punishing wrongdoers within its own ranks, the Islamic State is attempting to promote itself as a fairer and more accountable alternative to the status quo.

Toward this end, the Islamic State has used its legal system to discipline its own members—both civilian officials as well as combatants—for a variety of crimes including embezzlement of public funds, espionage, unlawful abuse of civilians, murder, and trafficking contraband products such as cigarettes, according to Syrians and Iraqis with personal knowledge of the cases. In some areas, the Islamic State has issued public statements urging civilians to report misconduct by its members. According to one report, the group placed a “complaints box” at a mosque in Mosul.

Such actions have led some civilians to view the Islamic State—however harsh its rule may be—as relatively more accountable than the Assad regime or the Iraqi government, which 91 percent of Sunnis believe is treating them unfairly. One Syrian from Deir Ezzor said that, while he disagreed with the ideology of the Islamic State, he had to admit that “its courts are fairer than the regime courts, and the judges are not influenced by wāstah [favoritism] or bribery.”

3. Justifying Taxation

The Islamic State’s legal system plays an important role in raising revenue by justifying taxation. Oil was initially assumed to be one of the Islamic State’s primary sources of revenue. But over time, the estimated proportion of revenue that the group derives from taxation has increased steadily and now dwarfs oil extraction by an estimated ratio of 6:1. Even in Deir Ezzor, the most oil-rich province in Syria, the Islamic State still obtains more than twice as much revenue from taxation as it does from oil, according to the group’s own financial records.

As the Islamic State’s territory has grown, so has its tax base. But taxation is a risky strategy, particularly in war zones like Syria, where the local unemployment rate is estimated to be as high as 75 percent in some areas and people cannot even afford to buy food, much less pay taxes. The Islamic State recognizes that taxation, in the absence of a legal framework that justifies its imposition, is indistinguishable from extortion.

To address this problem, the Islamic State has used its legal system to legitimize economic policies that might otherwise resemble organized crime. Photographs of tax receipts indicate that taxes are often paid at court buildings. Courts in Iraq have issued orders requiring Islamic State combatants to pay a 20 percent tax on war booty to its treasury. These examples indicate that courts and judges are directly involved in administering and legitimizing the tax policies that are critical to financing the Islamic State’s governance and military operations.

Conclusion

Legal institutions have played an important role in the state-building project of the Islamic State. As such, they can play an equally important role in its unraveling. The Islamic State’s claim to legitimacy rests heavily on its purported commitment to justice and accountability. The group claims that its own members and officials are bound by the rules of this system, and that none are above the law. As one official document states, “The Islamic State is just and there is no distinction between a soldier and a Muslim [civilian]. In the shari‘a courts, all are held accountable and no one has immunity, just as the Prophet said he would cut off Fatima’s hand [the Prophet’s daughter] if she stole.”

Such claims have become increasingly difficult to sustain in light of growing evidence that the Islamic State is not as rule-abiding as it purports to be. Reports of misconduct by Islamic State fighters and officials are becoming more common. One Syrian from the province of Deir Ezzor said that an Islamic State military commander there was overseeing an illicit trade in cigarettes, which the group officially bans. Also in Deir Ezzor, an official in the local zākat office reportedly embezzled an estimated one million Syrian pounds that had been earmarked for charity and fled to Turkey with the money.

Moreover, a growing number of the Islamic State’s own members—feeling discomfort with some of the group’s more extreme practices, including the enslavement of Yazidis and unapologetic killing of Muslim civilians in terrorist attacks—are abandoning the group. As these disillusioned former members condemn the Islamic State’s violence as unlawful and un-Islamic, the group’s internal hypocrisies and contradictions will become increasingly apparent to its supporters.

The eventual demise of the Islamic State is inevitable, but what happens next? As Iraqi and Kurdish forces recapture territory from the Islamic State, they face populations that are deeply skeptical of the ability of government institutions to provide justice, security, and basic services. The Islamic State came to power largely by exploiting the weakness and illegitimacy of existing regimes. It is only the most recent incarnation of a long tradition of extremism in Iraq and the Levant that flourishes in the shadow of states that have not earned the trust and respect of their citizens. In a survey of Iraqis conducted in 2012, only 4.8 percent of respondents said that they trusted the government “to a great extent,” whereas 30.2 percent said that they “absolutely do not trust it.”

As long as the structural conditions that enable violent extremism are still present, the remnants of the Islamic State—once it is defeated—will most likely reconstitute themselves in new forms or inspire successor groups with equally radical ambitions. Any long-term solution must involve a fundamental reorganization of political and legal institutions in Iraq and Syria in ways that promote legitimacy and the rule of law.

.jpeg?sfvrsn=6117c6bf_4)