The Law of Individual Disqualification in a Democracy

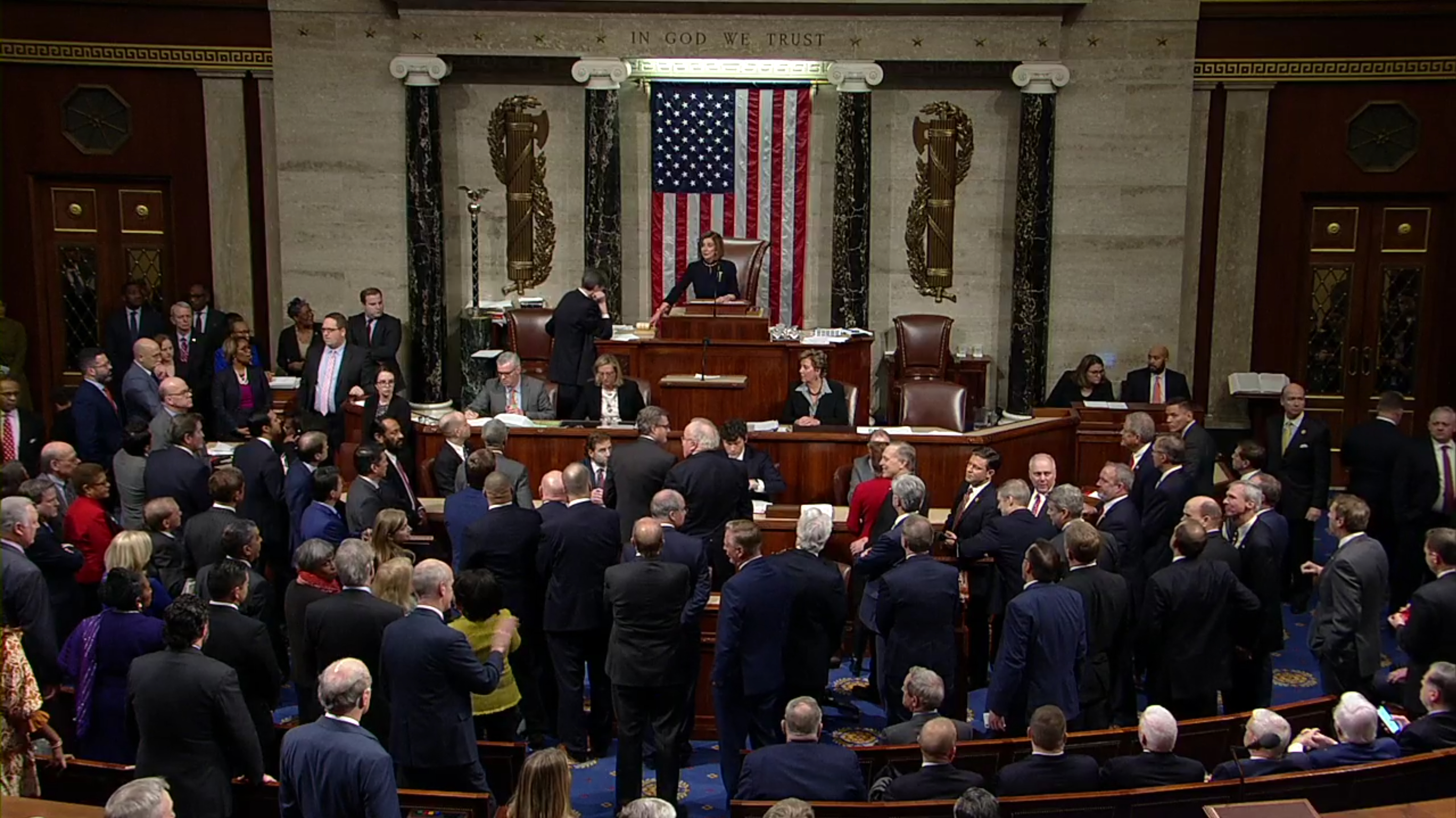

The Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol has raised questions on whether consequences should be imposed on any of the elected officials responsible. A comparative analysis of the methods of discipline against politicians in different democracies can illustrate the costs and benefits of disqualification in the American context and opportunities for improvement.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

In the aftermath of the Jan. 6 attempted insurrection, a largely unasked question concerns whether consequences should be imposed on any of the elected actors responsible. In particular, having worked against democracy, should they be allowed to continue to participate in democratic life? Or should they be disqualified from holding office in the future?

The absence of discussion on this question should seem odd: The United States appears to be in a moment when a constitutional mechanism to sanction individual antagonists of democracy seems urgently needed, and many other countries are in similar situations. But precisely because the question is so immediate, it generates a paralyzing partisan divide. The causes of the general crisis, in other words, stymie consideration of its immediate potential solutions.

The disqualification of individuals for their anti-democratic actions presents a specific iteration of a pervasive problem of democratic design: the tension between democratic self-realization and democratic self-destruction. On the one hand, democratic institutions have a reasonable claim to set the terms of political participation. The forms of elections, the rules for candidate and voter qualification, and ballot access rules are commonly matters for democratic decision. On the other hand, there is a risk that the power to set rules for the democratic game will be used to fence out disfavored groups, to entrench incumbents beyond electoral challenge or to create the image of democratic competition without its substance. Democratic mechanisms—including rules for disqualification—must be designed to advance the goal of self-government without facilitating malign entrenchment. Unbounded, the power to exclude specific individuals can imperil democracy. But its absence also means lost opportunities to deepen democracy and even to defend its basic existence.

In recent academic work, we have looked comparatively at the experiences of different countries to better understand the risks and rewards of methods of individualized discipline against politicians in democracies. The comparative lens, in our view, holds promise for avoiding partisan bottlenecks, and for thinking seriously about the constitutional mechanisms of democratic defense, because it taps into a richer pool of empirical data. Even when quantitative work with a large sample size is impossible, comparison provides some basis for evaluating efficacy,

This post summarizes our findings. We begin by examining the international experience with disqualification. Then, we circle back to the domestic U.S. context to sketch the present law and apply insights gleaned from overseas to the United States’ present predicament.

Disqualification in Democratic Constitutions

Almost all democratic constitutions, including the U.S. Constitution, contain instruments of democratic disqualification. These are mechanisms for identifying and excluding specific individuals or groups, whether through discrete adjudication or general legislative rule, from public office, either temporarily or permanently. Disqualification mechanisms differ from the ex ante categorical exclusions of certain classes of persons—such as noncitizens, minors, or, even more dubiously, women or racial and ethnic minorities—from public office. They are also distinct from criminal prosecution or conviction: Disqualification can and often is implemented through mechanisms that go well beyond the criminal justice process, while criminal sanction need not lead to political disqualification.

Two design choices are embedded in any disqualification mechanism. First, disqualification rules can operate either on the group level or on the individual level. That is, they can either disqualify actors en masse, because of membership in a certain party or affiliation with a discredited regime. Or they can work at the retail level, focusing on the conduct and characteristics of the individual actor at issue. Second, disqualification rules can be backward looking, focusing on the prior acts of an individual or group, or future focused, seeking to identify organizations or actors that pose ongoing and serious threats to constitutional stability.

These two choices create a framework of possibilities, and constitutional designers have experimented with all four possible permutations of these design choices. Consider examples of each.

First, backward-looking group rules have been adopted in many transitional democracies. In these cases, democracies have deployed rules screening, barring or even removing candidates from public office based on their association with a prior regime. Lustration, as this practice is known, is closely associated with the transition from communism after the Iron Curtain fell. In the Czech Republic, for example, some 15,000 individuals were removed or barred from public office after 1989. In the eastern portion of reunified Germany, lustration under reunification treaty provisions resulted in some 54,926 people being removed or barred from office. It has also been used in post-invasion Iraq, where the Baath Party was disbanded and its members excluded from office.

In practice, lustration is often applied with a narrower gauge than its formal scope might suggest. Practical and political concerns limit its operation. Where lustration has been widened, as in Iraq, it has interacted with ongoing political fissures in socially and politically damaging ways. One set of researchers found it “undermined” the government and military by depriving them of skilled personnel, while “fueling a sense of grievance” among those who lost their positions. At the same time, lustration regimes tend to linger beyond a political transition. Transitional mechanisms can help ensure that senior officials are not too “tainted” by association with the old regime. But they work best when they are temporary and use a sunsetting mechanism to minimize disruptions into ordinary politics.

Second, some systems use forward-looking group disqualification. German jurist and refugee Karl Loewenstein coined the term “militant democracy” shortly before World War II to describe “the use of legal restrictions on political expression and participation to curb extremist actors in democratic regimes.” Today, militant democracy’s most important institutional form is the ban on anti-democratic parties, deployed at various times in Germany, Finland, Czechoslovakia, Korea, France, Spain and the United Kingdom. Although not formally a bar against specific persons’ participation in politics, a party ban is often de facto a disqualification of known individuals.

Some 29 percent of working constitutional courts around the world have the ability to adjudicate the legality or constitutionality of political parties. Party bans have been imposed recently across regions and contexts, from Spain and Turkey to Israel and South Korea. For example, in 2014, a Korean court disqualified the United Progressive Party, a small left-wing party, citing alleged links with North Korea, at the behest of former President Park Geun-hye, after affiliates were arrested for an alleged plot with North Korea. In the modern U.S., party bans stand in clear tension with the First Amendment. But this legal barrier is exceptional, not the rule.

Perhaps the most important historical example is Germany’s. Under Article 21 of the 1945 Basic Law promulgated in West Germany after World War II, “[p]arties that, by reason of their aims or the behavior of their adherents, seek to undermine or abolish the free democratic basic order or to endanger the existence of the Federal Republic of Germany shall be unconstitutional.” Further, all parties’ “internal organization must conform to democratic principles”; their use of funds must also be transparent.

In 1951, the West German government asked the Constitutional Court to ban both the Socialist Reich Party and the Communist Party. In the Socialist Reich Party case of 1952, the court acted quickly and with relative ease, finding that the party’s platform leaned heavily on former Nazi ideas and imagery, that the party recruited unrepentant former Nazis to fill its ranks, and that it was organized in a top-down, undemocratic manner. The court seemed to struggle more to reach a ruling in the Communist Party case. It ultimately upheld the ban in a long, detailed opinion.

Third, there are individualized disqualification mechanisms that target bad behavior in the past. Some 90 percent of national constitutions with a presidency speak to impeachment. The substantive scope of impeachment varies. Crimes and constitutional violations supply the most common bases for removal. Although the procedural parameters vary greatly across countries, it is typically a lower legislative chamber that begins an impeachment by a supermajority vote. Ex post judicial review is often, but not always, available for impeachment. As in the United States, successful impeachment globally is quite rare. Our 2020 study found “between 1990 and 2018 … at least 210 proposals in 61 countries, against 128 different heads of state,” but only 10 successful removals. The evidentiary basis for analyzing disqualification by impeachment is correspondingly thin.

Interestingly, disqualification can also be done outside impeachment through judicial or administrative means. Consider the Israeli example. Under section 7A of the Basic Law: The Knesset, for instance, the legislature can prevent candidates from running for office if they engage in speech denying the Jewish and democratic nature of the state, inciting racism, or supporting the armed struggle of a state or terrorist organization against Israel. The same procedure is used for party and individual bans, imposed by a central election committee comprising current legislators and a Supreme Court judge. In application, it has sometimes been deployed against far-right Jewish candidates who incite hatred against Arabs. Supplementing this channel, Israeli courts have also adopted an aggressive program of removing officials and blocking appointments based on a judge-made concept of “good character.” Israeli law on the books disallows officials from serving in office upon conviction, but the Supreme Court has gone further to deem officials ineligible to remain in or hold office if currently under indictment. More broadly, the court has prohibited appointments within the government or military based on behavior showing poor character (such as sexual harassment) even when no criminal charges were filed. Such disqualification is becoming more frequent: There were 18 cases in the 1990s, 25 in the 2000s, but 21 in the first half of the 2010s alone.

Fourth, term limits are a forward-looking individual-level mechanism of disqualification. Term limits prevent officials from entrenching themselves in office by categorically barring terms of more than a certain number of years. The vast majority of presidential or semi-presidential systems include a term limit for their presidents. The 16 percent of systems that do not include a term limit tend to be non-democracies, often because the term limit was removed at the behest of an autocratic chief executive. The most common design, found in a majority of presidential systems, is the U.S. iteration: an absolute bar on any presidential reelection after two consecutive terms have been served. (This model became more popular after the U.S. passed the 22nd Amendment, replacing an earlier variant in which multiple nonsuccessive terms were allowed.)

A sizable number of systems retain an alternative form of disqualification, where presidents must leave office after serving either one or two terms, but only temporarily: They can return after sitting out a set period of time (usually one term). Chile offers an interesting recent example. Its past four presidencies have been held by two presidents from different sides of the political spectrum (Michelle Bachelet and Sebastian Pinera), each alternating service for one term. As with other forms of disqualification, then, term limits sometimes require only a temporary exit—in only a small number of systems (8 percent) is all possibility of reelection foreclosed.

What can be learned from this varied international experience? First, disqualification is a common feature of democratic political systems, even if that functionality is not always apparent among these various modalities. Second, it is often temporary—banned parties can re-form, lustration periods end and politicians can sit out a term before reentering the arena. We think this is wise, as it gives the democratic process time to adjust, without permanently excluding individuals and parties that have significant and enduring support.

Perhaps the most important design parameter is the mechanism for applying disqualification. Moving disqualification decisions outside elected bodies, we find, is correlated with increases in the rate of disqualification. Yet nonlegislative disqualification procedures remain quite controversial. Nonlegislative disqualification regimes in countries as diverse as Israel, Pakistan and Colombia have been critiqued as nondemocratic interventions in the political process that thwarted the popular will.

The Tangled U.S. Pathways for Disqualification

How might one apply these design principles to the undertheorized disqualification regime found in the United States? The U.S. already contains a surprisingly robust set of disqualification mechanisms. Three mechanisms of political exclusion target the executive and in particular the presidency: impeachment, with its sequel of a decision on disqualification; the anti-insurrectionary provision of the 14th Amendment; and the two-term limit for presidents.

First, the best-known vehicle for disqualification today is the impeachment process whereby the House and the Senate can act against the president, other executive officials or judges. The primary effect of impeachment is removal from office. But the Constitution states that conviction on an impeachment charge may have the additional consequence of “disqualification to hold or enjoy any office of honor, trust, or profit under the United States.” Second, Section 3 of the 14th Amendment is similar to lustration provisions found in other constitutions and laws around the world. In drafting it, Congress aimed to bar officials who had served with the Confederacy and made war on the United States. Section 3 is not just an instrument of Reconstruction: It is a permanent fixture of American democracy, albeit one that has fallen into desuetude. Third, the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution states that “[n]o person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice.” As conventionally understood, it means that any president who has served for two full terms is thereafter subject to a permanent ban on again holding the presidency.

How well do these mechanisms work? The Trump example suggests that the disqualification mechanisms in the U.S. Constitution are too fragmented and cumbersome to respond to contemporary threats to democracy. Impeachment is plainly too difficult a tool to wield, especially in light of the contemporary American party system. Experience with the Trump presidency and its aftermath suggests that impeachment may be all but dead as an effective disqualification tool. Neither Section 3 nor the 22nd Amendment sets out a process for its enforcement. At least until now, the amendment has been self-enforcing: Presidents who served two terms, such as Reagan, Clinton and Obama, have not tried to find workarounds to term limits. But what if a two-term president simply refused to leave office and ran again? If that person won in the Electoral College, would the 22nd Amendment make a difference? Could a federal court enjoin the president from taking the oath of office? We are uncertain. Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which has received a sudden infusion of scholarly and journalistic attention, shows some promise in responding to the Trump role in the Jan. 6 riot. But it has not been used since just after the Civil War, and even then it was not deployed often.

What Might Be Done?

The challenges faced by American democracy, as many observers have noted, are not unique. There is no reason why comparative and theoretical experience cannot inform reform efforts aimed at improving the present disqualification systems. Of course, the difficulty of constitutional amendment pursuant to Article V curtails the set of feasible interventions. But that does not mean there are no feasible reform possibilities.

First, Section 3 of the 14th Amendment could be revitalized and improved via a carefully crafted statute. The change would expand on and offer precision to the substantive standard, and create a heavy reliance on courts rather than political actors for enforcement, so as to limit opportunities for partisan arbitrage. Recall that Section 3 is written in general terms and is not textually limited to its origins after the Civil War. Comparative experience suggests Congress might consider giving it an “individualistic” valence more appropriate for a mature democracy. Congress passed a statute to implement it after the Civil War and remains empowered to do so now via its authority to “enforce” the terms of the Reconstruction amendments.

Such a statute would be useful to clarify both the substantive standard for application and the procedure for disqualification. It might also address other issues, such as the length of any disqualification, and could incorporate our argument in favor of temporary rather than permanent bans in most cases. As it is, Section 3’s threshold of “insurrection or rebellion” invites careless application and fatal underreach. It is probably too narrow to deal with the vast majority of modern threats to democracy. Incumbents now use a variety of quite legal means to entrench themselves in office. These do not easily fit within the terms “insurrection or rebellion.” One could, indeed, imagine a statutory framework fleshing out the meaning of “insurrection and rebellion,” elaborating in more detail a substantive threshold keyed to the need to preserve democracy as a going concern. Such a standard should be written broadly to catch future threats, rather than being confined to a particular historical incident. Attempts to subvert the electoral process should be at the core of such a “modernized” statutory definition. The standard would thus aim at specific, individualized acts undertaken to attack democracy, rather than (as with classic lustration mechanisms) membership in a tainted regime or group. Even with such a clarification, of course, Section 3 may remain—inevitably—underinclusive, and simply unusable against some kinds of democratic threats.

Further, the statute should address the process through which disqualification would proceed, as indeed the post-Civil War legislation did. Under the 1870 Enforcement Act, disqualification for most officials proceeded via the initiative of federal prosecutors in suits brought against allegedly ineligible state officials, with the federal courts acting as arbiters. A statute laying out a similar procedure may have some merit in the contemporary United States. A turn to courts would be a shift from the dominant constitutional paradigm for disqualification. Impeachment and legislative exclusion both operate through the political process and not through an administrative agency or a court. Indeed, the U.S. is striking in its virtually exclusive reliance on political rather than judicial or administrative routes for disqualification. We think courts can play an important role here.

Second, the near-moribund status of impeachment and (at least in its current form) of Section 3 as instruments of disqualification means that the 22nd Amendment’s presidential term limit is a singularly important protection for the U.S. democratic order. Placing a lifetime two-term limit on presidents, regardless of individual competence or attitude, is a crude way to protect democracy, with real costs. Popular and effective presidents are arbitrarily forced to leave office, despite popular opinion. At the same time, the clear, rule-like quality of the term limit can be a major advantage, avoiding the difficult and politically fraught judgments attending the standards for disqualification found in impeachment and in Section 3.

Yet the U.S. presidential term limit regime may be more vulnerable to evasion than commonly appreciated. It has been followed routinely since adoption in the mid-20th century. This period of tranquility may be deceptive. Unlike many democracies around the world, the United States has never experienced a serious term-limit evasion attempt. But past may not be prologue. It would be dangerous to assume that no such attempt will happen in the future. The current regime is riddled with ambiguity about enforcement. Should an incumbent president attempt an evasion attempt, whether brazenly or with subtlety, it is unclear which institution would be responsible for stopping it.

We think there is a powerful case for a framework statute setting forth a judicial mechanism for enforcing the two-term limit on chief executives. Ideally, enforcement would precede a presidential election and perhaps focus on the presence on the ballot of a candidate who is barred by law. At present, courts might steer clear of such a dispute, invoking the political question doctrine. A new law could force their hand. Such a statute would have to identify appropriate plaintiffs (for example, the attorney general of a state) and elaborate a clear norm detailing the 22nd Amendment’s application to different scenarios. It would also have to specify a remedy. For example, a district court could be authorized to issue an injunction against including an illegitimate candidate on state ballots. In effect, this is the mirror image of orders now issued mandating a candidate’s inclusion. It is also akin to an order the Supreme Court issued in April 2020 mandating that certain votes not be counted in an ongoing primary election in Wisconsin.

Third, if a constitutional amendment were on the table, one could reenvision disqualification from the ground up, constructing a system that was very close to a theoretical optimum (although tailored to the U.S. context). One new pathway could be keyed toward the protection of democracy, focused on identifying threats posed via individual acts (rather than group membership), and placed largely in nonlegislative hands. No system primarily or wholly reliant on supermajoritarian decision-making by Congress is likely to work well in the current American context, given the mix of a dominant two-party system and an increasingly polarized polity. This suggests a need to rely on other institutions, such as judicial or administrative agencies. The latter approaches, we have shown, are indeed common overseas. One way to structure such a system would be to retain the existing impeachment procedure as is, while also creating a new pathway for disqualification more reliant on administrative or judicial actors. In other words, we would propose decoupling impeachment and disqualification, creating two distinct institutional pathways. Section 3 already suggests this differentiation.

We would also suggest broadening the grounds for disqualification beyond “insurrection or rebellion,” a standard designed primarily to deal with the particular problems posed by the Civil War. This new standard would almost certainly lead to more aggressive disqualification decisions than the current baseline, which is essentially zero. That would be its aim. There is, of course, a corresponding risk of excessive use. This risk could be controlled with a clearer substantive threshold for political expulsion and more detailed ex ante guidance as to the actions sufficient to warrant disqualification. The language should focus on the kinds of actions that pose a threat to democratic stability, not broader issues of the character or morality of public officials. The focus in countries such as Israel, Pakistan and Colombia on character, and perhaps even corruption, sweeps too broadly into the democratic sphere.

Finally, in designing a new pathway for disqualification, the U.S. would be better served with temporary exclusions of the sort found elsewhere, rather than the more permanent bars contained in the current text of the federal constitution. Many systems around the world, as we have shown, use temporary exclusions from power as a way to defend the democratic order while softening the tension with democracy that is implicit in any disqualification regime. Disqualifications of five or eight years may help to preserve democracy against immediate threats, while also increasing both incentives for actors to deploy disqualification as a sanction as well as compliance with democratic norms. Temporary bans also allow for the length of disqualification to be calibrated to the degree of the offense and nature of the threat posed to the democratic order. And they give banned individuals a chance to come in from the cold if they are still truly popular.

Conclusion

In sum, the American way of handling disqualification, while sprawling, creaky, and fragmented, has both costs and benefits. On the one hand, it has proved resistant to capture and redeployment as an instrument of partisan entrenchment. On the other hand, it is far too slow to confront modern democratic threats. There are no perfect fixes. But reflection on comparative experience and democratic theories can help flush out opportunities for improvement. Given the prevalence of anti-democratic threats in recent years, both within the United States and globally, the need to develop more effective boundary conditions for democracy remains an urgent and unceasing task.