Lawfare Daily: Trump’s New Global Tariffs and the Court Fights to Come, with Peter Harrell and Jennifer Hillman

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

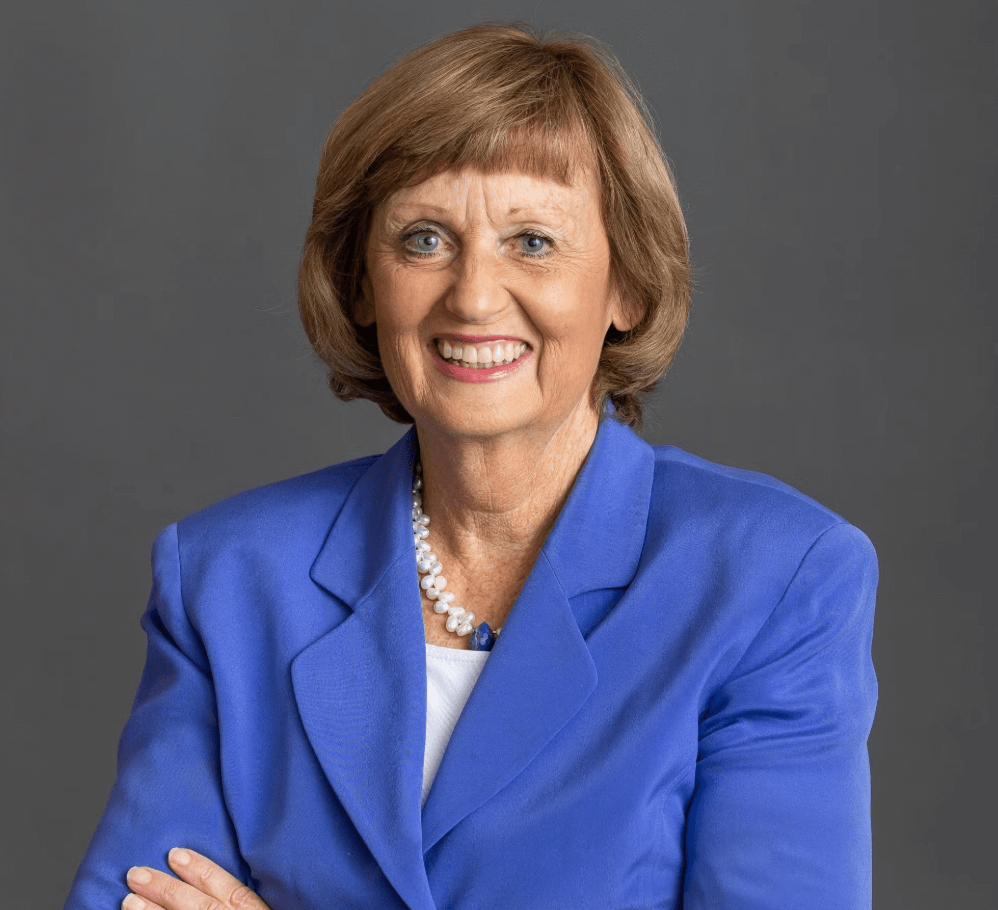

For today’s episode, Lawfare General Counsel and Senior Editor Scott R. Anderson sat down with Lawfare Contributing Editor Peter Harrell, who was previously Senior Director for International Economics on the National Security Council, and Professor Jennifer Hillman of the Georgetown University Law Center, a former member of the WTO’s appellate body and senior U.S. trade official, to discuss the new global tariffs that President Trump imposed last week and the legal fight that is beginning to emerge over them.

Together, they discussed how dramatic a break the Trump administration’s policies are from past practice, the logic behind them (or lack thereof), and whether his use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose them will really survive judicial scrutiny.

To receive ad-free podcasts, become a Lawfare Material Supporter at www.patreon.com/lawfare. You can also support Lawfare by making a one-time donation at https://givebutter.com/lawfare-institute.

Click the button below to view a transcript of this podcast. Please note that the transcript was auto-generated and may contain errors.

Transcript

[Intro]

Jennifer Hillman: All of this is occurring at a time in which the vast majority of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are already in debt distress. And again, the world economy is generally not in good shape, and now you're injecting this incredible shock and downward pressure on economic growth in the world.

Scott R. Anderson: It's the Lawfare Podcast. I'm Lawfare Senior Editor Scott R. Anderson, here with Lawfare Contributing Editor Peter Harrell, who previously served as Director for International Economics at the National Security Council, and Professor Jennifer Hillman of the Georgetown University Law Center, herself a former member of the WTO’s Appellate Body and senior U.S. Trade Official.

Peter Harrell: A tariff by its very nature, is something that is intended to have kind of a longer term impact, that is not really the kind of tool that one would, would use to address actual emergencies. And I think it's pretty clear that the framers of the statute, authors of the statute, did not intend for IEEPA to be used for tariffs.

Scott R. Anderson: Today we're talking about the new global tariffs, the Trump administration imposed last week and the legal fight over them that is beginning to emerge in the federal courts.

[Main podcast]

So we are living in a bit of a different world than we were a week ago, and I should note we're recording this on April 7 in the morning because it's a pretty fast-moving topic we're talking about today.

We, I guess, celebrated, question mark, what some are calling Liberation Day. Last week saw the imposition of a broad, unprecedented swath of tariffs across sectors, across trading partners imposed by the Trump administration that unlike the prior tariffs we see in relation to Canada and Mexico and China, seem to have stuck at least out the week, which is longer than those prior imposed tariffs lasted.

Peter, let me start with you. Can you give us a sense of the lay of the land? Give us the different parts about what we're seeing the Trump administration do. What is the, the contours of this policy they've implemented?

Peter Harrell: Well, first of all, Scott, thanks for having me on the podcast. Topic is very timely and very interested in discussing the tariff, the tariff news we've seen outta the administration.

So the, the Trump administration has issued sort of three different sets of tariff executive orders since it came into office back in January. So it issued an executive order back in February, targeting China for China's role in the fentanyl crisis. And Trump has used that executive order to impose two different 10 percentage point hikes on U.S. tariffs on China. So 20 additional points on, percentage points of tariffs on China; 10 percent coming in in February, 10 percent coming in in March.

Trump also issued an exec, a set of executive orders targeting Canada and Mexico also for their—this was also back in February—also for Canada and Mexico's purported role in the fentanyl and in the migration crisis. Initially those executive orders were going to impose 25 percent tariffs on most imports from Canada and Mexico; there were some exceptions, like 10 percent for Canada, Canadian energy, but, but 25 percent for most things.

And then when Trump brought those tariffs into force in March, those 25 percent tariffs on Canadian and Mexican imports, in light of market reactions and pressure from stakeholders, as well as some offers from the Canadian and Mexican government, Trump very quickly, within three or four days, exempted from those 25 percent tariffs products that qualify under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement, the USMCA trade agreement. So a lot of those tariffs were not actually in force.

Then last week, on Wednesday of last week, so-called Liberation Day, Trump issued another executive order that found that the sort of America's systemic and ongoing trade deficits were a national emergency, and he was imposing a new set of tariffs in addition to the prior sets of tariffs in order to address the, the, the trade deficit.

There are really two parts to those tariffs that he announced last week. The first is a 10 percent universal tariff, so basically 10 percent tariffs on all imports, from all countries. Then for some 60 countries, he announced quote unquote reciprocal tariffs. These were tariffs that were sort of up to 40 percent on countries ranging from the United Kingdom to Vietnam, with the, the percentage basically being calculated out of a formula of what it might take in order to close America's trade deficit with that, with that country.

If a country had a, a reciprocal tariff of above 10 percent—so Vietnam, for example, with about a 40 percent reciprocal tariff, that 40 percent included the 10 percent universal baseline tariff within it. So it was sort of 10 percent universal and 30 percent stacked on top of it.

One important final point on this—these tariffs are, are, are, are all kind of on top of, or in addition to the other tariffs. So China, for example, now has tariff rates of between 55 and 80 plus percent, depending on the good, because it had Trump's term one tariffs of 25 percent. Then you had the additional 20 percent from term two. And now you have a reciprocal tariff rate of 34 percent on top of that. So these tariffs are really quite expansive on, on top of other, other tariffs.

That's actually what I've just described for all these tariff rates—it's not actually all the tariffs we've seen. He also has product specific tariffs. We have tariffs on steel and aluminum around products, and he's threatened to bring into force tariffs on, on a variety of other products that would be kind of adjacent to all of these other tariffs that we have talked about.

One final, final point, just on the scale of, of, of the magnitude of this. If you look at the tariffs Trump imposed during all of his first term, they added about 1.5 percent to America's overall tariff rate. So, you know, he had a tariff rate that was at a high 2, low 3 percent; they added about one and a half percent to that. And that was almost entirely on China—not entirely on China, there were some steel and aluminum, other tariffs—almost entirely on China.

Over the last two and a half months, Trump has added more than 20 percentage points to America's average tariff rates. So you're seeing something like 14 times as much, as many new tariffs brought into force during the last two and a half months as you saw during all of Trump's first term.

Scott R. Anderson: So, needless to say, this is, as you've already laid out, Peter, a pretty dramatic policy swing, certainly for this administration, certainly compared to the actions we've seen other presidents take in the last few decades.

But I'm curious how it fits comparatively, historically. Jennifer, let me turn to you on that. I mean, put this, this set of trade policies into perspective for us. Is it just, you know, one step past what Trump and others have done before? Or is this really a huge paradigm shift in how we, we think about this policy area?

Jennifer Hillman: It is a very huge paradigm shift. This is taking United States tariff levels back to levels that we haven't seen in more than a hundred years. It is, in that sense, a, a massive magnitude.

The other thing that it is doing is completely changing the basis on which we impose tariffs. Since the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade was created in the 1940s, the United States and all of the other major trading partners have applied tariffs on what is referred to as a most favored nation basis, MFN, which basically says that you are gonna negotiate tariffs with everyone. And once you apply a certain tariff rate to a given country, you apply that same tariff rate to all of the other countries that are part of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which ultimately became the World Trade Organization, which is 166 countries.

So the notion was that if you're applying a, a 2.5 percent tariff on autos, that 2.5 percent tariff extends to all countries, again, under the WTO. So whether the car was made in Korea or in Germany or in Japan, it had a 2.5 percent tariff.

So the biggest changes are A, obviously a massive change in the magnitude of tariffs. Again, the United States had been a relatively open economy. We are now on the road to becoming a very closed economy in comparison to most other countries in the world. I mean, the average tariff on the vast majority of countries in the world is well below 10 percent. And now the United States is, average tariff will be well above 20 percent making us a very closed market in relation to everyone else in the world.

And secondly, we are now gonna start discriminating on a basis that we've not done since the 1940s, where one country gets one level of tariff and another country gets a different tariff level.

And I would say the third thing that is really unusual about these tariffs is the degree to which they're going after least developed countries, I mean, very, very poor countries in the world. If you look for example, the single highest tariff rate that these Trump tariffs would impose is on the little, tiny country of Lesotho. You know, again, this landlocked country in the middle of, you know, landlocked by South Africa. You know, again, a least developed country with a GDP per capita of $916. Not thousands, not millions—I mean, this is a very, very poor country.

So the bottom line is they don't have very much money to buy anything from the United States. And they are struggling very hard to ship us, you know, a limited amount of the diamonds that they happen to have and a limited amount of textiles and clothing. But because they don't have enough money to buy anything from the United States, they've been hit with these very high tariffs because of the way in which the Trump administration has calculated the amount of these additional duties that are being imposed under this, in theory reciprocal basis.

But the way they've calculated them is to simply take the amount of the trade deficit that that country is running with the United States divided by the amount of exports, divided by two. So, because Lesotho sent us a fair amount—again, a small, but nonetheless fair amount—of, of textiles and, and, and gemstones, but could not afford to buy anything from the United States, they have a big trade deficit with the United States, hence the reason for a 50 percent tariff on this extremely poor developing country.

And there are many other, you know, sort of least developed, you know, poor countries that are now being hit with these very high tariffs that has the effect of, you know, again, of dramatically endangering their economies. And again, to me, you step away from it, and all of this is occurring at a time in which the vast majority of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are already in debt distress.

And again, the world economy is generally not in good shape. And now you're injecting this incredible shock and downward pressure on economic growth in the world. So I, I don't think you can understate how significant these tariffs are.

Scott R. Anderson: I wanna dig deeper into this formula that the Trump administration has applied to come up with these tariff rates with every country in the world, because as you described, Jennifer, it, it is this really, really basic division problem, essentially subtraction and then division, right? You're basically looking at the trade deficit as the biggest variable in determining this rate.

And the, the, the express logic we hear is that a trade deficit is there because of some sort of unfairness and because of that trade deficit, that's what makes us a quote unquote reciprocal tariff, something that's responding to something else purportedly in kind.

Peter, lemme start with you on this—Jennifer, I welcome your thoughts as well—does that make any sense? I mean, it seems like the Trump administration's goal in this is to get to zero trade deficit, a trade surplus, I guess, or, or complete equality with every country in the world. Is that actually an economically optimal outcome or a goal that's worth driving towards?

And even then, it seems like actually you would still have the 10 percent threshold tariff, so even that wouldn't get you out of the tariff world. But somewhere beneath 10 percent is where countries stop having an incentive to, to try and correct a trade imbalance.

That's something that Trump has talked about for a long time. Is there a logic there, is there a reason we should be pushing towards that, that outcome? And is this an effective tool to even try and get there?

Peter Harrell: So, you know, there's been a long time debate in both academic and policy circles about whether there is an actual economic problem from America's structural and persistent trade deficits.

You know, you've seen some folks like my colleagues at Carnegie, Michael Pettis, who's argued that, you know, in a famous book called “Trade Wars Are Class Wars” that, that, that, that actually, there, there is a way in which these systemic deficits have kind of hurt working class Americans, and that if you had a more manufacturing oriented economy, you might see a sort of compression of the inequality we have in the U.S. and you might see some, some wage, wage benefits here.

He's also argued that sort of by allowing countries like China to develop these export oriented models, you've actually hurt workers in China as well, so it's kind of been anti-worker across the board with this imbalance global system. So you do have this view that maybe there is some challenges around persistent trade deficits.

You also have a large camp of economists that doesn't see any economic challenges around trade deficits and sort of argues, you know, much as I run a persistent trade deficit with Amazon because I buy lots of stuff from Amazon, —doesn't really matter, I mean, that's good for me, right? I get lots of stuff. I give them money. And that what really matters in the U.S. is, is our economy growing? Are we seeing real wage growth here in the U.S.?

You do have this debate in economic circles about the extent to which the trade deficit is itself a problem or not. The question though here is, is partly that kind of big picture academic question. It is also partly even if you posit that the trade deficit is a problem, is this formula and is this use of tariffs a sensible way to address the trade deficit there?

I think what you've seen over the last week is almost uniform argumentation that no, this is not a sensible way to address the trade deficit. You know, we've even seen a couple of the economists whose work was cited in the one-page formula that USTR put out on the calculation saying, no, no, actually this in no way reflects our work or how we would think about calculating this issue. So I, I think you've seen, you know, practically speaking this formula as a way of addressing the trade deficit, almost uniformly panned out of the, the, the economics profession.

And a part of that is a potential misapplication of the formula itself, but also more structurally, the fact America has a trade deficit is not just driven by our trade policies. It is driven by our domestic fiscal policies. It is driven by our open capital account and the fact that we try to attract foreign investment here in the United States, which drives up the value of the dollar and thus actually makes a little bit harder or more relatively expensive for us to export things.

So there are actually a huge number of factors that have gone into our more than 30-year-old trade deficit. And you're not going to be able to solve the trade deficit simply by looking at tariffs, even if you had a formula that you applied correctly, that might in some metaphysical sense, be intended to close the trade deficit.

Jennifer Hillman: You know, if I can, I'd only add, you know, just a couple of thoughts on that. I mean, I would certainly underscore, you know, that again, we have been running a trade deficit since 1975. And if you look at the level of that trade deficit, you know, it's ranged between, you know, again, less than 1 to as much as you know, overall, you know, more than 6 percent of our GDP—but there's no correlation between the sort of economic strength of the U.S. economy and when that deficit has gotten sort of higher or lower over time. So again, we, we've been doing this for a long time with no clear evidence that it has caused all of this economic pain.

Secondly, I do think there is a pretty universal view that while the tariffs might bring back some measure of manufacturing to the United States, that is not going to be correlated with bringing back jobs. Because again, if you look at really what's happened over, over this period of time, what you've seen is, again, a huge amount of automation and increases in productivity.

I mean, steel is a really good example. You know, if you looked again—I, I know this data because, you know, back some years ago when I was a commissioner at the International Trade Commission you looked at the data around the steel industry very carefully. And when, when I was doing that in, you know, again, 20 years ago it took between 10 and 12 sort of person hours, man hours per ton, to make a ton of steel. Today that number is less than one.

So you've seen a 12, 10-, 12-fold reduction in the number of jobs that are connected to producing steel. So even if we wanted to try to significantly increase the volume of steel production in the United States, it will not translate to a significant increase in the number of jobs. So, again, I, I think that notion of jobs and the trade deficit has to be, you know, significantly cautioned by those.

To the extent that you've seen, again, a big gap in wages, again, part of that is unequivocally a derivative of our, of our tax code, where we tax very heavily wages and labor. I mean, everybody that's earning a paycheck is paying 30, 40 whatever percent in, in taxes, and yet we tax capital at a very low rate. So some of that has been this driver, if you will, of, of the gap in income inequality— again, having nothing to do with, with trade or, or trade deficits.

You know, the other two points to sort of really note on this is these tariffs are applying sort of universally, including to all of the countries that we run a trade surplus with. So if the whole idea behind imposing a tariff is to get at the countries with whom we're running a trade deficit is not doing that to the extent that, again, there's a significant number of countries that the United States has a surplus with and we're nonetheless putting the 10 percent tariff on them. So logically, you know, in that sense, you know, that does not make sense.

And the last thing I'll say is the formula does not do at all what the Trump administration said it was going to do. It said it was going to look at the amount of tariffs that were actually being charged by these other countries on our goods. I mean, you heard the president saying over and over again, if they charge us, we're gonna charge them.

Well, they have not done that at all. They haven't, as far as we can tell, looked at tariffs in any way in terms of calculating this formula, and that they were then gonna also look at things like VAT taxes and other non-tariff barriers. And again, this formula does not do any of that.

Scott R. Anderson: One last aspect of this formula I wanna ask you about, Jennifer, is a lot has been made of the fact that it is focused on physical goods, on actual like trade goods and doesn't incorporate services.

How much does that change the picture? Does that really make this less effective if you're concerned about overall economic production and exchange, including services? Or is this a reasonable metric to be so focused on squarely as the Trump administration clearly is?

Jennifer Hillman: Well, there's no question that when you talk about tariffs, you are only talking about goods, 'cause you don't apply tariffs to services or to intellectual property rights or, or to other, you know, sort of in that sense, intangibles that are, that are highly traded.

Obviously it's very distortionary in the sense that, you know, again, 80 percent of the U.S. economy is in services. And all of the sort of growth that people are looking at across the globe is expected to occur in services. In other words, most, most economists looking at it say, we've kind of reached a plateau or are nearly reaching a plateau in just the sheer amount of goods that are likely to be traded.

So when you talk about goods, what you're really talking about is just shifting kind of where they're made and where they're, and where they're sourced from, but not expecting any significant growth in the overall volume of goods that would be traded. I mean, it'll be up and down a little bit, but we're not gonna see major growth in, in the trading of, or the production of, from a global perspective, of goods themselves.

So all the growth is in, is in services, particularly in digital services, and particularly in intermediate digital services. And none of this is gonna really capture that or help the United States capture and be more competitive in those, in those services areas.

Scott R. Anderson: And I think that leads to a pretty natural question, which is the other side of the equation we're beginning to see emerge as countries respond to this, right? The United States describes these as reciprocal tariffs. Other countries are not receiving them that way. We've seen already Canada, in response to the earlier round of tariffs, take some responsive measures. Other countries may be considering that.

Do we have a sense of what that looks like as of yet, and is it gonna be so limited to just sorts of tariff responses around physical goods? I mean, the Trump administration seems to focus on this 'cause it doesn't want to talk about the services components—harder to justify these actions in that lane—but does that mean other countries can't find other ways to clamp down or push back on areas where the United States may have more comparative advantage and may hurt the broader economic relationship more?

Peter, lemme start with you on that.

Peter Harrell: So, so we are definitely seeing countries gear up for retaliation. China, for example, announced actually quite significant retaliation last week, two days after Trump announced his reciprocal tariffs that includes both tariff based measures—China's imposing a 34 percent tariff on its imports of almost all U.S. goods—and it also includes some non tariff measures. So China is cutting off an additional set of critical minerals exports to the U.S. It also put a number of U.S. kind of defense technology type firms on its, its equivalent of sanctions and export control lists. And it's also beginning to gear up its kind of domestic antitrust and other regulatory apparatus to, to, to go after a couple of U.S. companies.

The European Union had postponed prior retaliation over steel and aluminum over Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs to the middle of this month, the middle of April, because it wanted to see what happened on April 2 and kind of have one package of retaliation. I think we will see Brussels retaliate in the coming weeks.

European Union is very clearly signaling it will also look not only at tariff retaliation, but also at non-tariff retaliation, including potentially going after the activities of U.S. digital platforms in Europe. For example, it could potentially impose new taxes on digital platforms operations in Europe or, or otherwise, look at, at ways to restrict digital services.

Also potentially looking at investment, sort of the role of U.S. investment banks and other banking services in Europe. And then Europe is also looking at precluding U.S. firms from bidding on public procurement contracts in Europe. Again, I'm not sure they'll do all of this, but they're clear, they're signaling very clearly, they are looking at kind of non-tariff retaliation here.

You know, I do want to make one kind of point on this, which is, although the Trump administration in its formula, you know, sort of excludes services, it only looks at goods, if you look at what the Trump administration is asking of some of our trading partners, it's actually asking for more services market access, right? One of the, the big complaints that Trump administration officials will make about the European Union on the trade front, is that they are already too restrictive on U.S. tech firms, digital services.

So it's, it's been interesting that they kind of want this both ways, right? They only wanna focus on the good trade deficit for the purpose of calculating tariffs, but one of the things they very much want out of our trading partners is more, more access for U.S., U.S. services firms. And so I think there's kind of a little bit of a, of an intellectual incoherence in how they are, they are thinking about this.

Scott R. Anderson: And that gets to the bargaining element of this, right? Like with these tariffs thus far, certainly with the first two rounds of briefly kind of weekend long tariff impositions—that's not entirely fair of the second one, but relatively brief full position of tariffs then a fairly substantial walk back in the Canada and Mexico context—the, the kind of underlying assumption of a lot of people is that this is some sort of bargaining position, bargaining technique, and that Trump's gonna trade a lot of this away.

And I think a lot of people had that expectation this time around as well. Or at least that seems to be perhaps a reason contributing to a less outright panic, at least in the first 48, 72 hours after Liberation Day, so to say as Trump has declared the day that he imposed these tariffs.

But we're having a lot of discussion about what the Trump administration wants to see, but it's not clear to me we're seeing a clear strategy or motion towards saying, here's our clear engagement of negotiations; here's what we're gonna do to get rid of these tariffs; here are our demands for these. Except at the highest kind of conceptual level that you flagged, Peter.

Jennifer, am I wrong about that? I mean, is there a more concentrated strategic negotiation plan? And if so, who's executing in the Trump administration? I mean, what are they trying to get and how are they trying to get it out of this?

Jennifer Hillman: Again, I, I think the answer is no. There is not a, a clear plan, or at least certainly not one that anybody can discern.

I mean, part of it is, to me, you start with, okay, the, this 10 percent tariff has been imposed on more than 200 countries. It is simply not realistic to expect that you're gonna reach bilateral agreements with 200 countries in anything resembling the near term. So unless they're prepared to walk away from that baseline 10 percent tariff applied to all, you know, we should just expect that 10 percent tariff to be there for quite some time.

And then again, as I said, I mean the, the, the amount of time and energy that it would take to start negotiating with many of these really small, least developed countries, you know, that are getting these impositions of, you know—I mean, Madagascar at 47 percent, Lesotho at 50 percent, you know, Laos at 48 percent. The amount of time and energy it would take to try to reach an agreement with all of the countries that are on this list that are getting these very high tariff rates is way out of proportion with whatever economic value might come from those agreements.

And again, if part of the reason they're not buying very much from the United States is their least developed countries where nobody has any money, again, it just makes no sense for the U.S. government to be wasting its time trying to do negotiations with these countries. They don't have anything to give.

But you then go to, okay, let's look at some of the bigger economies. I mean, go for example, to Korea. We already have a free trade agreement with Korea. How much were the average, you know, Korean duties on U.S. product? Nearly zero. So again, what is the negotiation going to be over with Korea? And again, you know, that goes to Canada, Mexico, et cetera, Israel—I mean a number of countries that are not charging tariffs on anything from the United States.

So it's clear that if you're only in the tariff lane, there's not a whole lot to negotiate over 'cause we're already at zero. So that means you're, you're, you're thinking, you know, sort of outside of, of the tariff lane.

And I will only say those are really difficult negotiations in terms of exactly what are you asking for, to the extent that they require another country to change its underlying regulations or, or again, its approach. Those are not gonna be quick or easy, to the extent, for example, that the Trump administration has complained about other countries, VAT value added taxes—that's nearly impossible.

I mean that, first of all, the vast majority of the world uses VAT taxes, and I don't see them as being willing to completely change their entire tax system just because the United States wants that. So it, it is gonna depend on what these asks are.

I will just say, I don't think it is clear at all from anything that the Trump administration has said, because if you step back and listen to this and ask why, why are we doing this? Why are we imposing all this pain and agony on not just the United States, but the world? It ranges from we wanna raise revenue—well, again, if that's the point, then what you're trying to figure out is what's the optimal tariff where the tariff is high enough to raise revenue, but low enough that you won't stop all imports from coming into the United States.

It's not clear that that's really a goal, because, you know, when you add up all the tariffs, for example, on China, many of the Chinese products are now subject to tariffs that are in a, in excess of 75 percent. Well, that means basically you don't import anything from China, and if you don't import anything, you don't have any tariff revenue. So what you know, is that really a goal?

I mean, the second sometimes stated goal, you know, is that they want to, again, build this tariff wall around the United States so that everything sold in the United States has to be built in the United States. Huge problem with that is we don't have the factories here to do all of this building of everything, and the thing that it will take in order to get there is imports of components and parts and everything else in order to build those factories. But if those are all subject to very high tariffs on steel, aluminum, et cetera, and all of the components, again, you won't get there.

The other thing that it will take to get there is a lot of time, years of time. And again, will we have that if these tariffs in the interim are, are crashing the economy, you know, putting a huge downward pressure on investment. I mean, who wants to invest in the U.S. economy if it's gonna be subject to all of these fluctuations and headed into a recession?

So again, I do think it is absolutely unclear to any of our trading partners what does the United States want? What's the point of these tariffs? And what do they need to do or say in order to try to get out from under them?

Scott R. Anderson: Well, needless to say, I think it's, there's a lot of concerns and questions about this set of tariffs policies, and there's a reason why we're beginning to see some erosion around support for them, both in Congress —among members of the president's own party, although I think it's relatively slow—in the broader public, and then in particular among companies; many of whom have talked about, have raised legal concerns about the prior impositions of tariffs, particularly because they're reliant upon the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, IEEPA, kind of broad statutory authority usually used for, for sanctions most commonly, or familiarly used for sanctions at least.

And now we're beginning to see legal challenges, or at least we have one legal challenge already filed in the Northern District of Florida by Emily Ley Paper Inc., incorporated—also doing business as Simplified—specifically challenging the imposition of China tariffs. This was filed last week; we're still waiting, I think our reply briefs and the other, the litigation to really get underway, but we have a complaint seeking injunctive and declaratory relief, basically saying these tariffs are unlawful uses of IEEPA.

Peter, talk to us a little bit about why the administration turned to IEEPA in this case and not the other more conventional tariff authorities that we've expect in this case, and some of the advantages, the reasons we might have done that, and also some of the vulnerabilities that come with that, that we're beginning to see at least this plaintiff try and capitalize on.

Peter Harrell: Yeah, so, so it was interesting to see the first lawsuit against IEEPA tariffs filed last week. As you say, that lawsuit was sort of formally filed only on the China tariffs. It's not filed on the action from last week. It was filed on the China tariffs that Trump first announced in in February. I do think we're gonna see potentially both an expansion of that lawsuit to cover other tariffs as well as other lawsuits coming into court.

Let's talk about why we're seeing this litigation. So, IEEPA, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, is a 1977 statute that Congress passed post-Watergate as part of an overall package of reforms to actually reduce presidential power across a range of different vectors. It is a statute that Congress clearly intended to give the president a pretty broad and flexible authority to respond to emergencies in international relations.

So, you know, if a country invaded another country, needed to impose sanctions on them, they wanted to make sure the president had a pretty broad authority to do that. I, I actually think looking at the legislative history, it wasn't intended only for national security purposes; it was also clearly intended, the language states in, in the statute states it can also be used for economic emergencies that originate overseas.

But there too, I mean, some years ago I actually interviewed one of the staff auth-, authors of the bill and it's like, well, look, this was, you know, post oil embargo, Arab oil embargo, you know; we're thinking about sort of sudden shocks in the international economic system that maybe would need would need to be addressed and so on.

But I think what, what, what is very clear about it is that it was intended to be used to deal with emergencies—things that, you know, come up suddenly and are unexpected and probably time limited in use. IEEPA has never been used for tariffs. It's been used more than 60 times since it was passed in 1977. First used in 1979 by Jimmy Carter to impose sanctions on Iran after the Iranian Revolution, been used by presidents ever since for sanctions, as well as other purposes. For example, most of the sanctions that President Biden imposed on Russia in 2022 were done under IEEPA.

But it's never been used for tariffs. And I think there are a couple of reasons for that. First—we can get into the details—I don't think it's legally, it's, it's, it is the very most legally unclear that it can be used for tariffs. I think it does not authorize tariffs. There is debate over that very least. It's legally unclear it can be used for tariffs.

And relatedly tariffs are generally not the kind of tool that you would use to respond to an emergency. You might like freeze an adversary's assets right during an emergency, or you might decide, you know, we are going into a conflict situation, we wanna, you know, cut off exports to a particular country. But a, but a tariff by its very nature is something that is intended to have kind of a longer term impact that is not really the kind of tool that one would, would use to address actual emergencies. And so I think it's pretty clear that the framers of the statute, authors of the statute did not intend for IEEPA to be used for tariffs.

Now, why is Trump using IEEPA rather than the many tools that Congress has enacted to give the president tariff authority, like Section 301 of the Trade Act in 1974, which is what Trump used for his term one tariffs on China? Well, it is because it doesn't have any procedural, any substantial procedural requirements. Under IEEPA, the president just has to declare an emergency pursuant to the National Emergencies Act, and then he can enact, take very substantial actions, which are not really subject to detailed administrative procedures.

So, the reason the president did this is he wanted to be able to impose very high tariffs within a couple of days across many different countries. He did not want to have to do detailed country specific fact finding that, you know, country X is engaging in unfair trade practices. And then here's my proposed response and I have to notice and comment for public comment my, my proposed response before I can adopt it. He wanted a tool that lets him sort of remake the global economic order at the stroke of a Sharpie. And, and that is what in fact we've seen him, what we've seen him doing.

That is also part of why I don't think IEEPA is an appropriate statute here because the framers of IEEPA never imagined this as something that a president could use to remake the global economic order at the stroke of a, of a, of a Sharpie. But that's why he's doing it, because he thinks it is the authority that would let him do that.

Jennifer Hillman: I'll only add just a, a couple things ‘cause again, I'm in, I'm in total agreement.

Part of it is to me, if you step back and think about it, you know, the Constitution gives to the Congress, not the president, the authority to impose taxes and set tax rates and again, to charge tariffs and set tariff rates. And so to me, what is extraordinary to think about is that here we are with the single largest tax increase in more than a hundred years, without Congress. And so to me, you have to step back and say, this cannot possibly be the way the Congress intended it—that you could have this massive, massive tax increase without any gracing the doors of the Congress.

And, and to me, you know, just to add in to Peter's analysis, part of the reason why this is very clear to me is that the wording of IEEPA and the authority that is granted to the president does not include the word tariff or duty at all. Those words do not appear in the statute.

And every other place in which the Congress has clearly delegated tariff authority, it has used those words, duty or tariff, within the statute and has included a process to determine how much the tariff or the duty should be, so that you do have to go through this process of having evidence and information and data that would indicate both that the tariff is necessary, and secondly, how much.

And the, the other thing that I think is really important is that what IEEPA does do is say that there must be a direct relationship between the emergency that's been declared and then the action that you're taking in order to address it. And I think that is one of the things that the, that the lawsuit that you mentioned that's been filed in Florida tries to get at, which is, you know, kind of what is the relationship between an emergency related to fentanyl—'cause that was what the original, you know, a set of tariffs on under IEEPA was, was directed at a public health crisis over fentanyl.

And part of the underlying argument here is, you know, what does a tariff on a T-shirt or a teddy bear or something else have to do with fentanyl and a public health crisis? And yet, that is unequivocally a requirement under IEEPA, that it must be necessary to address the particular emergency that's been declared.

Scott R. Anderson: Let me break that down a bit. Peter, I'll come to you on this because you as well as Jennifer and a few other folks have written a couple of really valuable pieces for Lawfare breaking down a couple of possible arguments about how IEEPA tariffs could be challenged. Although notably, these are different tariffs than we were talking about when you wrote that piece, which were, they were a little more targeted at the time. These are much broader, which may help certain arguments or hurt other ones.

And I think it's fair to say you can break IEEPA down into three different chunks, each of which has different levels of vulnerability, or potential to attack. One is the declaration of a national emergency, technically a National Emergency Act state, saying, well, is this a national emergency? Does it meet the criterion that is required for a national emergency or for the type of national emergency under the statute? Notably, usually highly deferential there—these plaintiffs do not even challenge that.

Then you have on the other end of the spectrum, the whole array of measures that IEEPA lets a president pursue. Jennifer is a hundred percent right that it does not say tariffs or import duties or anything that specific in there, but it is also at the same time, incredibly broad. It does this redundant verbiage where we see 30 different verbs about that mean kind of the same thing where they list over and over and over again, at 50 U.S.C. § 1702, that is often interpreted suggests breadth of scope in terms of what's being authorized, although not necessarily limitless. And it is worth saying the plaintiffs do attack this here 'cause of the lack of any specific discussion of tariff authority.

And then you have this relationship between the two. This idea is, is whatever the measures that the broad authority is being used for actually responsive to this emergency? Different parts of IEEPA say it has to be necessary to address the emergency; other ones say it has to be, I think it's, in order to address the emergency. That is the big, I think arguably the big, one of the biggest focuses here—other than a constitutional issue—in this particular complaint, separate from the absence of the tariff language.

Where do you think these tariffs, particularly these more recent ones, are most vulnerable and where do you think you're gonna see, they might see the courts get the most pickup among these arguments, or we may see future plaintiffs focus the most?

Peter Harrell: Yeah, so, so I, I break down the kind of potential legal arguments against use of IEEPA for tariffs, Scott, and do exactly the sort of same three categories that you do. You could argue whatever national emergency has been declared doesn't fit the, the, the, the scope of the National Emergencies Act. You could argue IEEPA doesn't authorize tariffs.

And then you could argue, well, even if IEEPA authorized tariffs, in some circumstances in this particular, whatever the particular circumstance is in this particular circumstance, tariffs aren't kind of, tailored in a way that would address, actually address the, the national emergency.

And I do think here you see some differences between the litigation that was filed against the China tariffs and potential litigation we might see against the action last week. So the China tariffs that are currently subject of litigation, as we discussed earlier, are related to or in response to the national emergency Trump has declared on fentanyl. And the plaintiffs in the, the challenging the China case, Emily Ley Paper, doing business as Simplified, don't even really challenge that. They acknowledge that the fentanyl crisis would fit within the scope of the National Emergencies Act.

And I think that the, the, the reason they don't challenge that is that IEEPA has been used in the sanctions context to address a vast array of crises out there. So, there is an IEPA sanctions program on cyber criminals. There is an IEEPA sanctions program on other, on, on global corruption type issues. And I think that if you just look kind of factually at the seriousness of America's fentanyl crisis, it's, it's pretty clear that a, a national emergency around the fentanyl crisis fits within the kinds of national emergencies presidents have declared over at least the last 20 years or so. Whether they really fit within the initial framers view of, Congress's initial views of IEEPA, think is a different question, but, but we have, this practice is built up over decades and that's why you don't see a challenge there.

I do think that if and when we see litigation against the universal and reciprocal tariffs, we probably are going to see a challenge based on the declaration of the national emergency because the president there argued that the structural trade deficit, the ongoing trade deficit, is the national emergency.

And the idea that there is an ongoing trade deficit that has existed—as Jennifer rightly corrected me—not just for 30 years, it's actually been for 50 years is somehow now a national emergency just defies the basic logic of, of anything you might consider an emergency. So I do think you'll litigate that issue with respect to the, the more recent, recent tariffs.

Then you have this issue of tailoring, like are tariffs tailored to the national emergency that has been declared? And, and here I think the, there are really two arguments. On the one hand, you can argue as Jennifer does that like tariffs on a t-shirt from China aren't really related to the fentanyl crisis. And there's like clear logic to that. How on earth are they related? The challenge that's going to be have to be decided by the court is that we have a longstanding practice in the sanctions space of imposing sanctions and indeed embargoing trade in goods that aren't directly related to the kind of conflict the sanctions are being imposed on.

So you could, I think, equally argue, you know, how is a ban on new investment in Russian t-shirt manufacturing—which is now banned like since 2022, you can't make any new investment in Russia—how is that related to Russia's war on Ukraine?

I think there are arguments you can make there, but that's gonna be the challenge because we have historically used sanctions as negotiating leverage, and we've had a view of like, you can use these sanctions as negotiating leverage to solve your problem. The Trump administration is gonna make the same argument on the, the t-shirt tariffs. They’re gonna say, well, yes, t-shirt imports have nothing to do with fentanyl, but we're creating leverage to negotiate with China and the court's just gonna have to sort out, you know, how how do, how do we see that tailoring?

I actually think the strongest argument is the, the, the final one, which is that you read this language in IEEPA and it simply doesn't say the word tariff. There are lots of other words in it. As you know, there are lots and lots of other words; there are lots of explicit things that IEEPA authorizes, but it does not include the word tariff.

And, and the word tariff is important here because if you look at who has the authority to impose tariffs under the Constitution, it is an Article I, Section 8, which says, Congress has the authority to lay and collect excise and duties and tariffs and all the rest. So, so that's a very clear, specific congressional power, which is textually in the Constitution, which is not included in IEEPA.

Now, the legal theory that IEEPA would allow you to impose tariffs is because IEEPA does allow you to quote unquote regulate the importation of property in which a foreign national has an interest. That's how you can use it for embargo purposes. And so the argument would be, well, if you can regulate the importation of property, presumably tariff is a derivative of regulate. I don't subscribe to that. I think that if Congress intended this to be, include tariffs they would have or should have said so directly, and they, they, they simply haven't.

Scott R. Anderson: The other aspect of this legal challenge and of the debate around this is a constitutional one. They—the legal challenge in this complaint phrases it in terms of the non-delegation doctrine, a doctrine that most people assume it's been more or less dead for the last, mostly almost the last hundred years, but keeps hanging around in kind of indirectly affects about, you know, canons of interpretation, the way the courts approach different statutes, interpret them more narrowly.

The major questions doctrine, as this court has kind of revivified in a very strong way, which says essentially you know, the strongest version non-delegation doctrine would say there's certain things that Congress just can't delegate, or at least needs to do so clearly and expressly to delegate them. And you could see some version of that around, you know, Article I, Section 8 authorities or, or something else, right around, around the taxation authority or tariff authority.

A weaker version would say, well, if it, if it doesn't seem like this is within the scope of what Congress intended, that's a reason to say maybe this isn't really how we should be reading the statute, that's something closer to the major questions doctrine.

Where do you see those arguments fitting in here, Peter? And then I'll turn to you, Jennifer. Is this likely to see a constitutional pushback? Is that really gonna be a grounds on which to resolve this dispute as these plaintiffs are pushing forward? Or, or is it more of a background consideration that's hanging around over this whole debate, particularly in light of this court where the major questions doctrine is one of the things that its been most aggressive about in the last four or five years?

Peter Harrell: So I do think that at the very least, these tariffs, this, the sweeping view, the, these sweeping tariffs, which are, you know, really economically significant, raise a major questions doctrine issue. The major questions, doctrine being this kind of doctrine that the Supreme Court has either invented or revived in recent years, depending on how you look at it, that basically says where a president wants to use a statute to enact a kind of very major policy change, Congress has to have spoken clearly on it.

And this came up a couple of times during the Biden administration. It came up, for example, when the Biden administration wanted to use a 1970s statute, the Clean Air Act to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. And the, the, the Court basically said, look, you can't use this 1970 statute to regulate greenhouse gas emissions because Congress didn't speak clearly that that was part of the, the statute, and there are huge economic impacts from your doing so.

And I think actually the parallelism with using IEEPA for tariffs with using the Clean Air Act for, for greenhouse emissions—actually really kind of quite a bit of parallelism, right? Where you're seeing use of an old statute for very new and very economically dramatic purpose. So a lot of, a lot of parallelism there, and I think the major questions doctrine should clearly apply here.

I think the major questions doctrine is sort of part of this broader issue of non-delegation, right. Which is where Congress, it's going to delegate an authority to the president, it A, has to have, you know, given the president articulable principles, some limiting principles about how to do so.

And it's interesting 'cause if you go back and you look at the arguments in favor of IEEPA being, authorizing tariffs, one of the major arguments that comes up is that Nixon, President Nixon had used IEEPA's predecessor statute—the Trading with the Enemy Act in 1917— to impose 10 percent tariffs on all U.S. imports in 1971 for four months when he took the U.S. off the gold standard.

They were worried about balance payments issues, and so he used IEEPA—well, actually didn't at the time. It's interesting—in the history, he didn't actually cite IEEPA when he imposed the 10 percent tariffs, but then when litigation by a Japanese zipper manufacturer came to challenge these 10 percent tariffs that were imposed for four months, he cited TWEA, the Trading with the Enemy Act, as part of a, the, the sort of ex ante rationale for the tariffs.

And the court ended up upholding those tariffs in 1975 in a case called Yoshida. But if you read that case, that case says very clearly—and the court looks at the, and addresses the non-delegation issue quite clearly—it says there's this issue about, you know, can Congress in TWEA delegate its tariff authority to the president?

And they basically said, well, we don't have to address that in big picture, because what we actually saw is tariffs of 10 percent for four months in response to a very clear event—Nixon pulling the U.S. off the gold standard. And so there is actually dicta in that case that says, look, you know, in other circumstances there might be a non-delegation issue here, you know, if tariffs were being used for other or broader purposes.

So I would say even in the case that supporters of IEEPA cite as sort of why IEEPA authorizes tariffs, there is actually quite extensive dicta around the non delegation issue that suggests that tariffs like what we saw last week—kind of universal, open-ended and forever—would violate the non-delegation doctrine.

Jennifer Hillman: I would love, I would love to add just a little bit more because I do think the, the sort of a couple of really important historical things coming out of this Nixon's use of the Trading with the Enemy Act, just for context.

First is the actual language of what a president can do under the Trading with the Enemy Act and under IEEPA are virtually identical. So that is why there is a lot of attention on this old Nixon use of it. But I do think there's a couple, three really important distinctions between sort of then and now.

One is the original trial court in this Yoshida case said no, that the language in the Trading with the Enemy Act, the same language under IEEPA does not provide tariff authority. Just does not, because again, it doesn't use those words, doesn't have the right guardrails in terms of, you know, this notion of, of non-delegation.

It was the appeals court that then overruled and said, well, you know, again, we're not ruling in general whether or not this language really provides authority, but we note a couple of things: A) that the tariffs were temporary; B) they were not applied on all goods, so certain goods that were already duty free, they did not change those; and third, that none of the tariffs exceeded tariff rates that Congress had already enacted. And so for the court, this was really important that even in this limited temporary way, they were not exceeding congressionally authorized tariffs.

Well, again, if you then look at what the Trump administration has now done under these IEEPA tariffs, they have violated all of those. Again, there's, there's no notion that these are temporary. Secondly, they have exceeded the statutorily enacted tariffs on every country with whom we have a free trade agreement. All of our free trade, trade agreements, again, were passed by the Congress, and so the Congress has said that the appropriate level of tariffs for Korea, for Colombia, for the Dominican Republic, et cetera, is zero. I mean, that's a statutorily enacted tariff schedule. And yet these tariffs, you know, totally violate it.

And the third thing to me that was really interesting coming out of the legislative history is the Congress clearly understood and saw this Yoshida case as saying, okay, in this limited instance with respect to balance of payments problems, we can appreciate that tariffs are the right tool to address a serious balance of payments problem. So they separately enacted Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 to say if there is a serious balance of payments problem, yes, you may use tariffs up to X amount for up to 150 days.

So again, they said, we, we get it that there could be this emergency on balance of payments, but to me that's significant. That is saying that there is this limited tiny carve out of when the president has been delegated tariff authority to deal with balance of payments, which to me suggests that the rest of IEEPA is not a delegation of tariff authority.

And again, to me the last thing is just the magnitude. I mean, the notion of enacting the largest, you know, tariff and tax increase in history without the Congress to me just cannot be squared with the unequivocal constitutional language, Article I, Section 8. This is uniquely a power that is given to the Congress. You do not want one person to be able to decide everybody's taxes and everybody's tax rates.

Scott R. Anderson: So I, I think that's phenomenally useful. And I will say—I, I think I have to say out there as somebody who wrote a piece for Lawfare I think six years ago, five years ago, pointing out Yoshida as, as a case that probably supports the idea that President Trump could impose tariffs in the limited context of Mexico back when he was considering it, I will double down and say, I'm not sure that thesis holds nearly as well for what we're seeing now, unless anyone thinks I'm necessarily on the other side of this argument who's been digging into Lawfare’s archives on this stuff.

But let me turn to one other avenue of contestation that we haven't heard much about, and that is the international architecture that we have still for global trade. A focus of U.S. policy for decades, a mechanism that I, you know, for the elder millennials that certainly such myself that we grew up with, you know, grew familiar with massive protests around because it was perceived as so unpopular, as such a point of concern. But that does not seem to be playing a huge role, at least so far in the debate over these tariffs, and, and frankly, you don't hear a lot of people talking about it, anticipating playing a huge role.

Where does that fit into this? Is, is, does that global architecture still have a major role to play? And is, is it likely to yield pressure on the Trump administration? And if not, why not?

Jennifer Hillman: So I would argue that in many ways yes, it does, but whether it plays any role is really largely up to everyone else.

You know, as I've mentioned, I think, you know, the Trump administration again, has nothing—I mean, what I think you're referring to is really fundamentally the rules of the World Trade Organization.

And again, just to review the bidding, you know, what the World Trade Organization has done, and again, the problem I think for the world is that the last time there was a significant negotiation around these rules and these tariff levels was in the 1990s, the early 1990s. The WTO was established in 1995. And the tariff negotiations that that fed into that WTO were largely completed in the early 90s.

So that's the last time in which the world engaged in a significant tariff negotiation, tariff binding exercise. And we have to remember in the early 1990s, we fundamentally weren't trading with China, with India, with South Africa, even to some degree with Brazil and some of the others. I mean, it was a much more limited world that was aggressively engaged in these tariff negotiations.

But what was agreed in 1995 is that whatever the tariff levels were, you put them into a schedule and you in essence bound your tariffs to that rate and said to the rest of the world, I will not charge tariffs that are above the rate that I have put into this—I have agreed, I have put into the schedules that I am posting at the WTO. Every country that joined the WTO, every country that was a member put those schedules in and said, this is the maximum amount of tariff that I can charge on my goods. And that if I want to change those levels, I will engage in negotiations with everybody under Article 28 of the GATT.

So the United States, again, the Trump administration in doing this, in wholesale breaking all of those tariff bindings is to that sense, you know, sort of blowing up this longstanding commitment of, I will not charge tariffs in excess of my bound rates and I will charge tariffs on an MFN basis, meaning I will not discriminate. The rate for one is the rate for all. So those two fundamental principles, Article I and Article II of the GATT, I mean the very basics, have been effectively blown up.

The question for me is then what is the rest of the world gonna do about it? Because I think it puts the, you know, the rest of the world in a very significant dilemma. Most of the rest of the world still believes in the WTO; still believes that we're better off with a rules-based trading system, where everyone more or less remains committed to those fundamental non-discrimination, fundamental tariff bindings as a way of not having chaos all over the world.

So I think many countries are at least, you know, starting to just file a WTO challenge against these Trump tariffs, just to have it on the record that the tariffs are in fact a violation of the, of these fundamental principles.

The theory is also that, that by filing that case, you're indicating, I'm still wanting to behave under the rules. And, and the idea conceptually is that I, my retaliation only occurs if it's been authorized by the WTO; that at some level, this ability to push back on the United States should be also subject to the WTO rules.

And I think the third thing that you are starting to see in a way that I think we haven't seen before, is many of these countries think about banding together, getting together within the WTO to try to figure out whether there could be a collective or common pushback against the United States. Because again, many, for the many of these smaller countries, you know, standing alone, they, they have no chance of, of even getting in the queue to try to negotiate much less working now at something else.

So, and again, the, the head of the WTO has already issued her own, I mean, Ngozi has issued her own statement, sort of cautioning countries, at the same time offering assistance. Let's come and talk about this at the WTO. Let's figure out whether there is a better approach than everybody just going down their own individual lane. Trying to engage in some semblance of maintaining something other than just utter chaos in, in the trading system by saying the rules still matter and for most of the world that they do.

And whether or not, again, there could be a better collective approach to the Trump administration to try to say, you need to at least think about the degree to which you are—you, United States, have significantly benefited from the rules-based trading system, and whether you really do want to walk away from it and create the kind of chaos and lawlessness that will occur in the absence of it.

Scott R. Anderson: We will have to leave the conversation there, but something tells me this issue will be with us for a while longer. Until next time, Peter Harrell, Jennifer Hillman, thank you for joining us here today on the Lawfare Podcast.

Jennifer Hillman: Thank you very much for having me.

Scott R. Anderson: The Lawfare Podcast is produced in cooperation with the Brookings Institution. You can get an ad-free version of this and other Lawfare podcasts by becoming a Lawfare material supporter at our website, lawfaremedia.org/support. You'll also get access to special events and other content available only to our supporters.

Please rate and review us wherever you get your podcasts and look out for other podcasts, including Rational Security, Allies, The Aftermath, and Escalation, our latest Lawfare Presents podcast series about the war in Ukraine. In addition, check out our written work at lawfaremedia.org.

The podcast is edited by Jen Patja. Our theme song is from Alibi Music. As always, thank you for listening.