Learning from Islamic State-Khorasan Province’s Recent Plots

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: The Islamic State-Khorasan Province is perhaps the jihadist group most active in international terrorism. Nicolas Stockhammer of Danube University-Krems and Colin Clarke of the Soufan Group examine the group’s targets, methods, and recruiting, drawing lessons for counterterrorism from its successes and failures.

Daniel Byman

***

March 2024 marked the five-year anniversary of the collapse of the Islamic State’s physical caliphate. Since then, its core organization in Iraq and Syria has been mostly on the decline, but the global network of affiliates and branches that the Islamic State established is alive and well. Some franchises have garnered a far more prominent role, and the Afghanistan-based Islamic State in Khorasan Province, or IS-K, has assumed the mantle of the most operationally active and capable of its provinces.

IS-K cells and operatives have carried out successful attacks overseas, and still other plots have been thwarted—most recently, a planned attack targeting a Taylor Swift concert in Vienna. This record provides valuable lessons for countering the group, providing information about its tactics, techniques, and procedures for target selection, idiosyncratic plotting strategies, and command-and-control related to attack planning. Several thwarted plots in Europe since 2022 entailed joint, cross-border planning and logistics by alleged IS-K supporters (many of them Tajiks or Turkmens), suggesting a transnational network component extending the group’s external operations capabilities. These recent plots also demonstrate how the organization is changing, and counterterrorism officials should take note of IS-K’s increasing recruitment of young teenagers and new uses of social media.

The North Rhine-Westphalia Nexus

On Easter Monday 2023, German police observed a group of probable IS-K operatives conducting surveillance on several rides at a funfair in Deutz, a neighborhood of Cologne, Germany, taking selfies and photographing the surroundings. According to news reports, one of them made the “tawhid gesture”—an expression of monotheism in Islam used by Islamist extremists as a symbol of radical ideology and militancy—while riding on a merry-go-round.

On July 6, 2023, the German Federal authorities and Dutch judiciary arrested nine presumed IS-K members. Among them was an individual known as the “sheikh,” who is likely the spearhead of the German North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) terror cell; he is a suspected IS-K operations planner of Tajik origin, who was based in Breda in the nearby Netherlands. The group met an astonishing 58 times in Breda or NRW. The ringleader is alleged to have discussed possible terrorist attacks in Europe during meetings with IS-K instructors.

The cell, primarily composed of Tajik nationals, is believed to have scouted the Deutz funfair and the Ibn Rushd-Goethe Mosque in Berlin—a liberal congregation that openly supports the LGBTQ+ community—to assess their suitability as targets. The local organization apparently had extensive contacts within a transnational jihadist network. They coordinated money transfers with a IS-K financial operative in Türkiye, which has become something of a logistical hub for IS-K. According to German security authorities, the suspects attempted to procure firearms and tested a suitcase bomb. The German IS-K network even considered acquiring an infrared-guided anti-aircraft missile when a contact believed to be fighting in the Donetsk Basin offered to sell them a Stinger surface-to-air missile for $5,000. Their contacts extended to Austria, involving a transnational cell that was planning attacks on cathedrals in Cologne, Vienna, and Madrid on New Year’s Eve as revelers rang in 2024.

The NRW terror cell looked to attack a soft target, the carnival, as well as a target linked to progressive social leanings, the LGBTQ-friendly mosque. The targets demonstrate a desire to cause mass casualties and strike a symbol of liberal socio-cultural and religious values, something anathema to IS-K’s hardcore sectarian and ultraconservative agenda. The terrorists were able to move money from one country to another, and the weapons to be used would have included small arms and explosives if the jihadists had been successful in procuring the items on their wish list. The plot demonstrates a significant level of planning and commitment, evidenced by the dozens of in-person meetings conducted by the rather large cell. As with many other IS-K plots, the individuals involved were of Central Asian origin (several from Tajikistan, one from Kyrgyzstan, one from Turkmenistan), and in this particular instance, members of the German cell were in contact with IS-K operatives abroad. Seven of the nine suspects arrived in Germany via Ukraine.

As with many terrorist plots that are disrupted, this case appears to be a combination of effective counterterrorism by German security forces combined with perhaps poor tradecraft and operational security on the part of the terrorists, who met several dozen times, providing law enforcement authorities with ample opportunity to monitor their network. This high “traffic” had drawn attention and resulted in some members of the group being placed under surveillance.

Teenage Terrorism

In early 2023, the Austrian National Intelligence Service received a warning, likely from the United States, about a possible terrorist attack in Vienna involving jihadists affiliated with IS-K. A group of three teenage Austrian Islamists of Chechen and Bosnian origin—aged 14, 17, and 20—were implicated in a terrorist plot to attack the 2023 Vienna Pride Parade with an assault rifle and machete. The cell included two brothers who were radicalized by consuming videos from Islamist influencer preachers on TikTok and had begun sharing IS-K propaganda online. Police searches before the parade uncovered a large cache of cut-and-thrust-weapons, an extensive trove of extremist material, a written oath of allegiance to the Islamic State’s then-leader Abu Hussein al-Husseini al-Qurashi, an 18-page guide to fighting in urban environments, and a homophobic pamphlet defaming the LGBTQ+ community.

The 14-year-old seems to be a key figure among the suspects. It was he who had created propaganda and expressed a desire to join IS-K in Afghanistan upon turning 18. Investigators found the adolescent had initiated a Telegram channel for jihadists across Europe in which attacking an LGBTQ+ parade had been discussed. His initiative brought him to the attention of IS-K operatives, who encouraged his militancy. He is accused of possessing bomb-building instructions and raising money through a chat group to purchase weapons for IS-K. The Telegram group served as a platform for discussion with fellow jihadists across Europe—including suspects from Germany, Belgium, and the Balkans—serving as something akin to a micro virtual terror planning hub.

IS-K and its supporters are increasingly using such closed peer-to-peer encrypted chat groups to engage in virtual planning. Plotters in one location provide online instructions to supporters on how to carry out attacks in their respective target countries. These virtual entrepreneurs’ instructions can take different forms: recommendations on targeting, the modus operandi, ideological and/or logistical support. In the case of the Telegram group started by the Austrian teenager; it was discussion in the group that brought the Vienna Pride Parade to the plotters’ attention as a potential target.

The advanced plot to attack Vienna Pride was likely coordinated with a German Tajik IS-K cell, which had been penetrated beforehand. German Bundeskriminalamt (Federal Office of Criminal Investigation) reported that an undercover informer had said that the three brothers arrested in Austria had received orders from operatives in Germany. The IS-K entrepreneurs deliberately chose younger jihadists as they could expect less punishment. Terrorism scholar Peter Neumann’s analysis of all arrests related to jihadist terrorism in Western Europe since October 2023 shows that two-thirds of terror suspects are teenagers, with many of them radicalized online. All three suspects have since been released from prison, but investigations are still underway.

NRW has become somewhat of a hub for IS-K operatives because of the density of Tajik refugees given asylum in Germany after arriving in the country from Ukraine. The Tajik diaspora is the primary vector for IS-K recruiting, and IS-K’s efforts have also targeted other Central Asian diaspora communities successfully. Moreover, as the prominent case of Molenbeek in Brussels in the mid-2010s suggests, some diaspora communities (however not only Muslim) in Europe could potentially segregate from the rest of society. Under such conditions newly arrived migrants perhaps struggling with their identity, could be more vulnerable for radicalization and recruitment. Finally, the proximity of NRW to the Dutch border allows for cross-border operations, allowing networks coordinated by encrypted online communications to span multiple countries.

The New Year’s Eve Plot

Another plot involved a transnational seven-person IS-K cell of mostly Tajik origin, which planned to attack St. Stephens Cathedral in Vienna and Cologne Cathedral. German police suspected the attackers had planned to conduct a vehicle attack targeting the large crowds gathered outside Cologne Cathedral, adjacent to the central train station, around midnight on New Year’s Eve. Initial evidence also suggested additional planning for another attack in Madrid.

In early December 2023, a 30-year-old Tajik—allegedly the handler of the group—was observed filming St. Stephen's Cathedral, checking it for surveillance cameras and tapping the walls for stability. The German tabloid Bild also claims that he carried out similar scouting in Cologne, and he may have also taken photos and video of the popular amusement park in Vienna, also in preparation for a potential attack.

Like other IS-K attack plans in Europe, the New Year’s Eve plot targeted a religious institution, which conforms to the group’s sectarian ideology. And like some of the other scenarios, the New Year’s Eve plot also involved individuals from the Tajik diaspora. The jihadists planned to conduct a vehicle attack, a popular and effective tactic of Islamic State terrorists in the West during the Islamic State’s apex, when vehicle attacks in Nice (2016), Berlin (2016), Stockholm (2017), and New York City (2017) combined to kill more than 100 people and injure many others. The choice of a vehicle is opportunistic and seeks to maximize both lethality and psychological damage. The amusement park in Vienna is another soft target, similar to the IS-K plot targeting the carnival in Cologne. Security officials were able to prevent the plot from proceeding primarily because of the group’s conspicuous behavior, both online as well as during their reconnaissance. Even before scouting the sites, members of the cell were under police surveillance because of their Telegram chats.

Other European Plots

In late March 2024, French President Emmanuel Macron mentioned that there had been two IS-K plots disrupted in France in the previous months but did not reveal further details. In April 2024—again in NRW—four teenagers suspected of planning Islamist terror attacks in Dortmund, Düsseldorf, Cologne, and Iserlohn were arrested. The suspects—including two girls aged 15 and 16 and a 15-year-old boy—were planning to target churches or synagogues using Molotov cocktails and knives. More recently, police arrested a German-Moroccan-Polish man linked to IS-K at Cologne Bonn Airport. The suspect had applied to work as a security guard at stadium events during the UEFA Euro soccer tournament, but was denied when investigators found suspicious recordings and discovered that he had transferred $1,700 in cryptocurrency to IS-K. In late July, Belgian police arrested three individuals of Chechen origin believed to be part of IS-K’s broader network. The individuals did not have a specific target—the plot was broken up in its early stages—but the group was preparing to purchase the precursor chemicals for triacetone triperoxide (TATP), an explosive used in other Islamic State attacks in Europe in the past, including the March 2016 Brussels metro and airport attacks. Even without a specific target, the proximity to the Paris Olympics led authorities to quickly disrupt the network.

Most recently, on August 7, 2024, two Islamist teenagers were arrested in connection to a major terrorist plot to attack before or during Taylor Swift concerts in Vienna. The two teenagers, age 17 and 19, are accused of having prepared an attack that would have targeted the outside ring of the stadium where Swift was scheduled to perform using TATP, cut-and-thrust weapons, or possibly a car. The 19-year-old suspect—Beran A. (nicknamed “Mo” after Mohammed), who is of North Macedonian descent—quit his job at the end of July, made a statement that he had “many great plans,” and changed his appearance. The younger suspect, who has Turkish-Croatian roots, was employed for a few days by a facilities company that was supposed to provide services in the stadium on the evening of the first concert. Though Austrian authorities have said that they believe the suspects were self-radicalized and did not receive instruction from the Islamic State, they noted that Beran A. had sworn allegiance to IS-K in a Telegram chat in early July. During a raid at Beran A.’s home in Ternitz, a town 45 minutes south of Vienna, police found explosives and jihadist propaganda. According to Franz Ruf, director general for public security at the Austrian Ministry of the Interior, the findings indicated “concrete preparatory acts.”

The attackers had already begin implementing their plans, and the investigation into the plot is still ongoing. All three Taylor Swift concerts scheduled for Vienna were canceled due to the threat. As with other plots, international intelligence sharing played a key role in intercepting the attackers. U.S. intelligence agencies initially detected the threat to the concerts, and passed information to the Austrian authorities and Europol.

These recent foiled IS-K plots in Europe highlight the urgent threat of IS-K’s growing capability to inspire, organize, and coordinate attacks. Together with the most recent IS-K attempts to recruit individuals from disenfranchised communities across borders, these dynamics demonstrate the group's strategic and tactical evolution. “The danger from Islamist terrorism remains acute,” German Interior Minister Nancy Faeser warned recently, describing IS-K as “currently the biggest Islamist threat in Germany.” That threat extends beyond Germany and could encompass most of Western Europe, as the recent arrests in Belgium demonstrate. As IS-K experts have noted, the shift to focusing on external operations is a deliberate one, part of the group’s strategy as articulated by its current emir, Sanaullah Ghafari.

IS-K’s Repeat Targeting of Iran

In 2024 alone, IS-K has launched several successful external operations, two of which involved significant casualties. In early January, IS-K conducted a double suicide bombing in Kerman, Iran, that killed more than 80 people and wounded an additional 284, according to some estimates. IS-K officially claimed the attack on its Telegram channel, naming both of its operatives, who were Tajik. The attack bore all the hallmarks of an Islamic State attack, including a coordinated suicide attack aimed at a highly symbolic, sectarian target, the memorial procession of former Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force commander Qassem Soleimani.

The Kerman attack is notable because the United States intelligence community, under its duty-to-warn directive, informed the Iranians that a terrorist attack was imminent based on intelligence the United States had gleaned. Despite this, the Iranian security services were unable to prevent the attack, leading to accusations that Tehran is too involved in conflicts abroad and not focused on protecting Iranians at home from terrorist attacks.

The attack in January 2024 followed two other successful IS-K attacks in Iran, both targeting the Shah Cheragh Shrine in Shiraz and causing casualties, in October 2022 and August 2023. Both of those attacks involved Tajik members of IS-K. Iranian intelligence claimed that at least one of the attackers was trained in Afghanistan.

Targeting Iran makes sense for IS-K on account of the role of Iranian Shiite militias in defeating the Islamic State in Iraq. Shia Popular Mobilization Units, many of which were sponsored by Iran, were significant in the Battle of Mosul. Iran has long served as an attractive target for the Islamic State and its regional affiliates, particularly IS-K, given its geographic location in neighboring Afghanistan, highly sectarian agenda, and its growing capabilities to conduct external operations. As with several of the failed plots in Europe, the targets in Iran involved a sectarian element. The attackers were Tajik, as with many other IS-K external operations. The attacks on Shah Cheragh were carried out by gunmen, and the use of suicide bombs is unique to the Kerman case. If it is true that one of the attackers trained in Afghanistan, the Kerman operation is an example of a directed attack, unlike the plots in Europe.

Spillover Effects Hit Türkiye

Türkiye is both a logistical and facilitation hub for IS-K, and in January 2024, a target as well. In late January, two gunmen stormed the Santa Maria Roman Catholic Church in the Sariyer district of Istanbul, Türkiye. Hamza Amirjon Kholikov and David Tanduev, both from Tajikistan, were apprehended and charged with committing the attack. One person was killed in the attack, which likely would have been more lethal if the assailant’s weapon had not reportedly jammed. Following the attack, Turkish authorities rounded up and arrested 47 individuals of Central Asian origin. The Islamic State’s central organization claimed responsibility and attributed the attack to its “Türkiye province,” but governments have disclosed IS-K’s involvement. Given the religious affiliation, the attack would fall in line with the organization’s sectarian agenda.

Türkiye has served as a logistical hub for both the Islamic State and IS-K. In November 2021, the Turkish government froze the assets of Ismatullah Khalozai, who was accused of operating an international money transfer business in Türkiye on behalf of IS-K. More than a dozen suspected IS-K members have been detained in Türkiye over the past two years. According to an 87-page Turkish indictment reviewed by CNN, foreign fighters from Central Asia use Türkiye as a transit hub, relying on a network of safe houses in Istanbul, with some continuing on to Iran and then Afghanistan to receive training before being deployed elsewhere to conduct attacks. In recent years, Turkish intelligence has arrested IS-K militants who were planning attacks against Swedish and Dutch diplomatic buildings and religious facilities in Istanbul.

The Istanbul plot involved Tajik militants attacking a sectarian target using small arms, all standard elements of IS-K external operations. Even if Turkish authorities can prevent additional attacks on their soil, the country will likely remain an important logistical and facilitation hub for the Islamic State’s global network, including its financial networks that are used to fund the group’s organizational and operational capabilities. Some of the IS-K terrorists implicated in the March 2024 attack targeting Moscow traveled to Türkiye shortly before returning to Russia to launch their assault. Because it is a convenient country for migrant workers to renew Russian permits—and because so many migrant laborers in Russia are from Central Asia—Türkiye has also become a significant recruitment hub for IS-K.

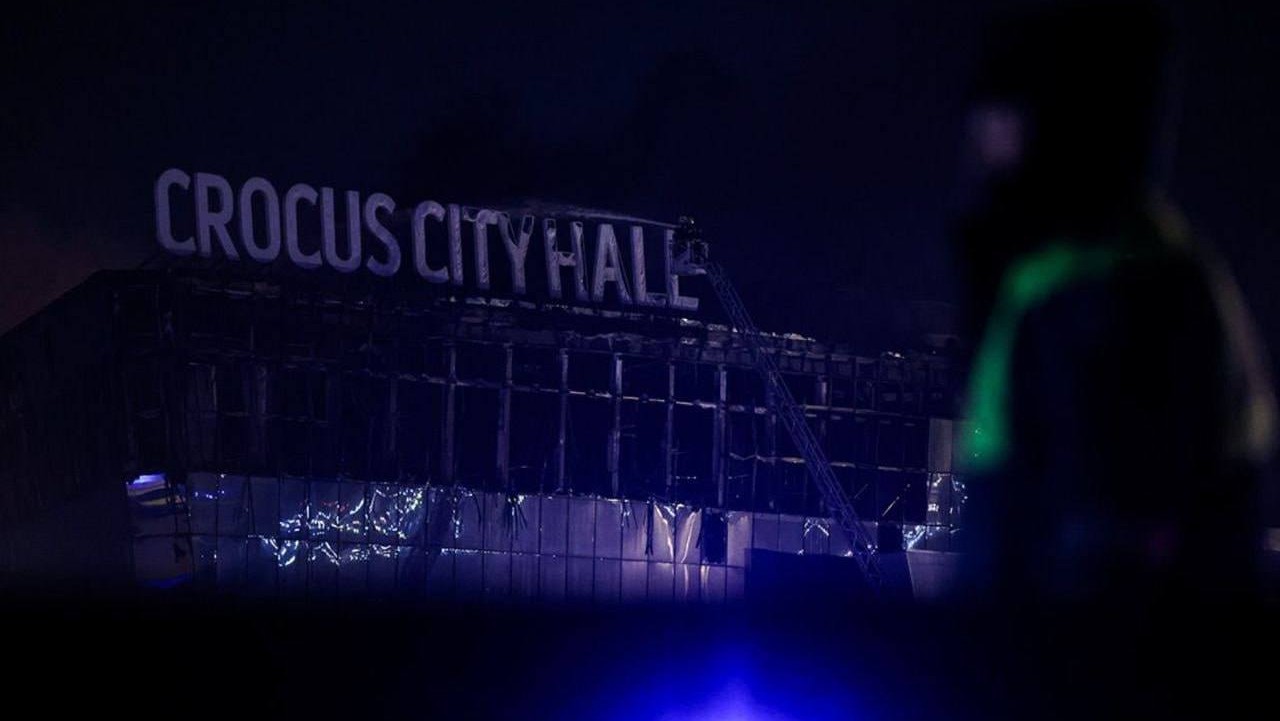

The War Comes Home to the Kremlin

That March 2024 IS-K attack on the Crocus City Music Hall in Moscow was the realization of the Islamic State’s ongoing focus on attacking Russia. IS-K propaganda had been fixated on Russia in the lead-up to the attack, criticizing Russian President Vladimir Putin and threatening revenge for Russian aggression against Muslims in Chechnya, Syria, and Afghanistan. In the Moscow attack, a four-person team of terrorists conducted a mass shooting and arson attack at a music venue, a soft target that the jihadists knew would have minimal security. Some of the victims had their throats slit—a level of extreme violence that is part of the Islamic State’s brand.

The IS-K attackers killed 145 people and wounded another 551 at the venue, making it one of the most devastating terror attacks on Russian soil, reminiscent of attacks by Chechen militants at the Moscow Theatre (2002) and Beslan School (2004). The attackers in the Crocus City Hall attack filmed the violence, and the attack was claimed by the Islamic State’s media apparatus, Amaq. And as with many of IS-K’s other recent attacks, the perpetrators were Tajiks. The Associated Press reported that one of the attackers reportedly confessed during an interrogation that he was recruited by the assistant to an Muslim preacher via a messaging app, although it is unclear if this was a forced confession.

Similar to the Kerman attack, Russian authorities were warned in advance about the attack but still failed to prevent the carnage. The Kremlin had received terror threat warnings from multiple intelligence services—from not only the United States, but apparently Iran as well.

In its claim of responsibility, the Islamic State said that it targeted Christians in its attack in Moscow, indicating a sectarian intent even if the target was a music hall, a classic soft target. The perpetrators were Tajik, another IS-K mainstay, and the weapons used included small arms, firebombs, and knives. The recording of the attack and its for propaganda is unique to the Moscow attack among IS-K operations. The Moscow attack evoked a previous Islamic State attack that targeted the Bataclan music venue in Paris in November 2015. The Crocus City Hall terror attack could be a template for future IS-K external operations, which was effective not just in terms of its lethality but also in its psychological impact.

Making Sense of IS-K’s Operations

An assessment of these IS-K plots reveals several important characteristics of the group’s operations and suggests an accelerated approach to transnational networking, both online and in the physical world.

Targets and Motivation

All of IS-K’s recent plots have been motivated by sectarianism to one extent or another. Churches, synagogues, and cathedrals have been recurring targets. The memorial procession for Qassem Soleimani also has a sectarian angle, as he was the figure most closely associated with the rise of Shiite militia groups in the Middle East. These plots have also involved various soft targets likely to yield high body counts, from amusement parks to concert venues. The focus on the LGBTQ+ community has been a distinctly European element of IS-K planning, and authorities should remain vigilant about this threat.

Capabilities and Weapons

The capabilities of the plotters have varied, with some demonstrating an understanding of operational security while others have been surveilled, arrested, and charged by law enforcement authorities after details of their plots were revealed. In the successful attacks, weapons included small arms, firebombs, knives, and suicide bombs, while unsuccessful plotters aspired to use similar means and, in one case, were ambitious enough to attempt to acquire a shoulder-fired missile. The targeting and modi operandi indicate a pattern—soft targets with symbolic value and a sectarian element attacked by small cells using vehicles, small arms, knives, or explosives. The focus on soft targets, compared to harder targets such as military or government institutions, could simply be a reflection of IS-K’s limited capacity to carry out operations, at least in the West.

Recruitment

IS-K relies on an extensive propaganda network to recruit and radicalize new followers and supporters. Local IS-K sympathizers predominantly used Telegram channels as an exchange platform and virtual planning hub for potential terrorist activities. IS-K recruiters, propagandists, and entrepreneurs frequently use codes in their internal communication via instant messaging channels. IS-K cadres intentionally appeal to teenage jihadists in Europe, like the plotters in Vienna, and seek to inspire them to conduct opportunistic attacks. The design and content of IS-K’s propaganda, including its Voice of Khorasan product, includes memes and other culturally relevant ways of connecting with younger audiences designed to resonate with the German-speaking youth demographic it targets.

Young recruits from Gen Z and Gen Alpha prefer TikTok, where influencer preachers serve as role models for a new Islamist communication strategy of content creation. Everyday topics and youth problems are deftly framed and given an Islamist basis or interpretation. This low-threshold proselytizing has been a gateway drug for radicalization, and consumers of this content have gone on to seek out more overtly extremist media. IS-K’s propaganda apparatus remains critical, and it has diversified significantly over the past several years and has extended its reach. IS-K propaganda is now available in more languages, but the messaging remains consistent, with references to “infidels,” “apostates,” and all kinds of hated minorities and enemies.

Structure

The European plots and attacks demonstrate IS-K’s various approaches. Some have been meticulously planned by smaller cells while others have been spontaneous and opportunistic, with lone perpetrators taking the lead. This is reminiscent of the Islamic State’s plots at the group’s apex, when it relied on a mixture of directed attacks in which terrorists received specific in-person training and orders, inspired attacks by sympathizers, and attacks coached by virtual entrepreneurs, who reached out to supporters in the West and provided instruction without direct, face-to-face contact.

This remote direction seems likely to continue. Before the Olympics, French intelligence identified a dozen IS-K “handlers” based in Afghanistan and throughout Central Asia who make contact with IS-K supporters in Europe and attempt to convince them to carry out attacks. If the individuals agree, IS-K terrorists then direct these individuals remotely, putting them in touch with others who can provide fake documentation, weapons, and other logistical support to conduct a terrorist attack.

Lessons for Counterterrorism

Two aspects of IS-K’s recent plots seem striking: The plotters and attackers are younger than ever—as young as just 13 years old—and their radicalization was enabled online, in some cases through TikTok. Also, their planning was augmented by special Telegram channels comprising a network of international peers. Countermeasures must adapt to the demographics of a new generation of plotters and perpetrators. Countering their radicalization will only work if the target group is properly addressed and their focus on social media is taken into account.

Disrupting these virtual networks is essential and requires a public-private partnership, with governments and policymakers working with social media and tech companies to implement an approach to content moderation and takedown. Though efforts along these lines have been ongoing for years, they have lost their urgency since the collapse of the Islamic State’s caliphate and require greater attention. Infiltrating these networks—through informers to obtain human intelligence and through monitoring and intercepts to gain signals intelligence—must be part of a broader strategy.

IS-K attacks in Afghanistan have declined. This is likely the result of several factors. U.S. and Afghan operations prior to the U.S. withdrawal decimated IS-K foot soldiers and eliminated important elements of the group’s leadership. That trend might have continued if not for the disastrous U.S. troop withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021. However, since then, the Taliban’s continued efforts targeting IS-K have also contributed to the group’s shift from conducting attacks in Afghanistan to external operations focused on targets outside of the country.

IS-K’s plots targeting Europe and other foreign countries is part of this evolving strategy. Preventing IS-K external operations and disrupting its transnational network must be a priority for U.S. and European security services. These persistent threats demonstrate that counterterrorism operations are still a necessary part of homeland security. No one wants to return to the days of the Global War on Terrorism. But a large-scale terrorist attack on U.S. or European soil could initiate another conflict and sap resources, upending the most well-intentioned efforts to compete with great powers and near-peers.