The Legal Limits on Trump’s Reprisals Against Impeachment Witnesses

If the president tries to go after career civil servants, he may trigger some significant legal consequences—including renewed scrutiny of his own conduct.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

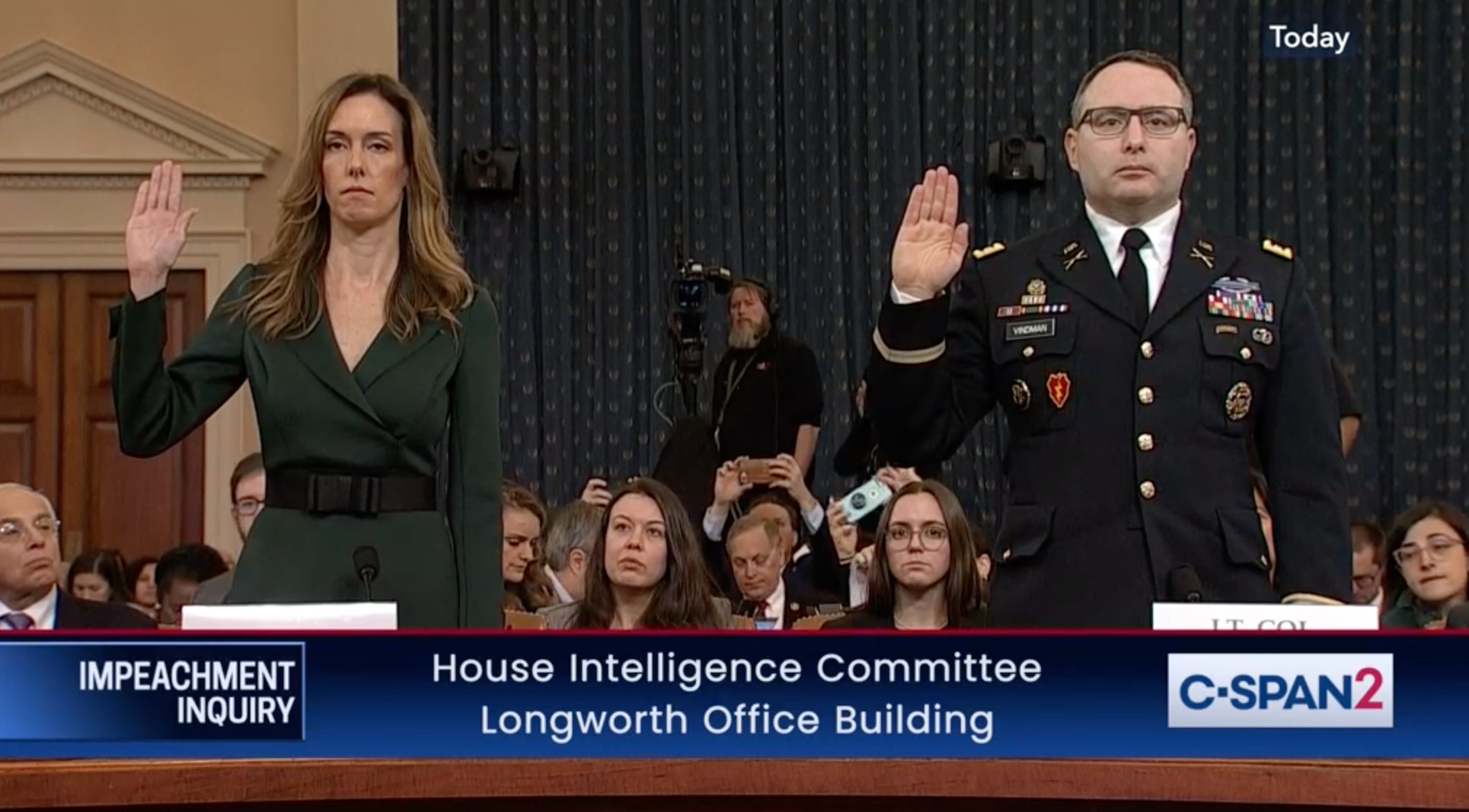

This past Friday, Feb. 7, just days after his acquittal in the Senate impeachment trial, President Trump launched what some fear may become a campaign of reprisal against those federal employees who testified against him in the House’s impeachment proceedings. Late in the afternoon, the White House ended the National Security Council (NSC) details of impeachment witness Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman and his brother Lt. Col. Yevgeny Vindman, both of whom were escorted from the building in an unmistakable signal of disrespect. Around the same time, fellow House witness and U.S. Ambassador to the European Union Gordon Sondland also received word that he was being recalled from his position. By the end of the day, no one who participated in the House’s impeachment proceedings still held a White House position or ambassadorship, though several remained in career positions in the leadership of federal agencies.

As the New York Times writes, the president “made no effort” to hide the vindictive purpose of the expulsions, which aimed to retaliate against Alexander Vindman and Sondland for their decisions to ignore the White House’s brazen directive not to cooperate with the House impeachment probe—and intimidate others who might consider similar disobedience in the future.

But the president is already pushing up against the legal and practical limits on his control over federal employees. While Trump may be able to remove officials from certain political positions with limited repercussions, there are far more constraints on what he can do to career civil servants. And pushing against those limits is likely to place Trump back in the same difficult position he only recently escaped: with his efforts to solicit political favors from Ukraine back under independent scrutiny. As a result, the president may not have much more leeway with which to continue his campaign of vengeance.

No law prohibits federal employees from testifying before Congress, at least so long as the testimony in question does not include classified or other statutorily protected information. Beginning with the 1912 Lloyd-LaFollette Act, Congress has expressly affirmed that federal employees have a “right … to furnish information to either House of Congress”—a right that has generally received bipartisan support. Congress has even enacted laws that threaten to withhold funding from officials who attempt to interfere with this right.

The executive branch, however, has long maintained that the president has the exclusive constitutional authority to “supervise and control the work of subordinate offices and employees of the Executive Branch” and to “protect national security and other privileged information”—an authority that Congress cannot interfere with through legislation like the Lloyd-LaFollette Act. So while Congress is not obligated to make unauthorized disclosures illegal, the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel maintains that Congress “may not bypass the procedures the President establishes to authorize the disclosure to Congress of classified and other privileged information by vesting lower-level employees with a right to disclose such information to Congress without authorization.”

Consistent with this position, federal agencies generally maintain policies that prohibit employees from independently communicating with Congress. Current State Department regulations, for example, direct employees to route congressional subpoenas and other information requests to the assistant secretary of state for legislative and intergovernmental affairs, who must authorize any response. Failing to follow these instructions is not a crime, but it can serve as a basis for disciplinary action. If the Trump administration were to justify its actions taken against Sondland and Alexander Vindman—the latter of whom Trump has described as “insubordinate”—it would most likely point to policies like this. (It would be harder for the administration to explain its decision to also remove Yevgeny Vindman from his position at the NSC.)

But such policies are by no means the final word on when federal employees may speak to Congress. In coordination with prior presidential administrations, Congress has also adopted a number of laws that are designed specifically to protect whistleblowers within the federal government who disclose information about possible misconduct—including those who do so to Congress. Most federal employees fall under the Whistleblower Protection Act (WPA), while members of the intelligence community fall under the separate Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act (ICWPA) and military personnel are covered by the Military Whistleblower Protection Act (MWPA). Each statute operates differently, but they accomplish similar objectives: protecting federal employees from job repercussions for pursuing protected disclosures. This makes these laws a major obstacle to any efforts by Trump to punish civil servants for cooperating with the impeachment investigation.

The MWPA arguably provides the broadest protections, as it extend to “communicat[ions] with a[ny] Member of Congress” provided they are not “unlawful,” including “[t]estimony, or otherwise participating in or assisting in an investigation or proceeding” relating to conduct “reasonably believe[d] [to] evidence[] a violation of law or regulation … [or] an abuse of authority[.]” The WPA similarly protects any disclosure—including to Congress—that the employee or applicant “reasonably believes evidences ... any violation of any law, rule, or regulation, or ... an abuse of authority,” so long as that disclosure was not specifically prohibited by law or executive order. The ICWPA, meanwhile, doesn’t protect direct communications to Congress, but it allows members of the intelligence community to forward “urgent concern[s]” relating to “[a] serious or flagrant problem, abuse, [or] violation of law … relating to the funding, administration, or operation of an intelligence activity within the responsibility and authority of the Director of National Intelligence involving classified information” to the inspector general for the intelligence community, who then initiates a process that is intended to end in disclosure to select members of Congress. This is the same process that notoriously broke down in the context of Ukraine.

In all three cases, employees who pursue protected communications and related processes are protected from prohibited personnel actions—including demotion, removal, the denial of promotions and other benefits, and even adverse consideration in future rehiring and promotion decisions. Importantly, these protections are not solely statutory but have generally been incorporated directly into agencies’ rules and regulations. This eliminates the sort of conflict between the political branches anticipated by the Justice Department’s objections to the Lloyd-LaFollette Act, and makes clear that protected disclosures are also consistent with relevant agency guidelines—meaning they should not be a basis for disciplinary action under the executive branch’s own rules.

Whistleblower laws and policies, however, are limited in scope. The MWPA applies only to members of the armed forces, while the ICWPA applies only to employees of, and contractors within, the intelligence community. The WPA applies to most civilian agencies but only to positions in the competitive service and excepted service as well as career appointments in the senior executive service. It also excludes those positions that are determined to be of a “confidential, policy-determining, policy-making, or policy-advocating character” or that the president has determined must be excluded to preserve the “conditions of good administration.” In effect, these limitations allow the president to retain control over “Schedule C” positions—a reference to the Office of Personnel Management’s classification of various hiring authorities—as well as other types of political appointments. Those who engage in protected disclosures while holding these positions will still be protected from adverse treatment if they hold or later apply for positions within the scope of the whistleblower statutes. But their ability to retain political appointments outside the WPA’s scope may not be guaranteed.

This may help explain why Trump’s reprisal campaign has thus far been limited largely to removal from White House positions and high-profile political appointments such as ambassadorships. Like other ambassadorships, Sondland’s position was a political appointment subject to Senate confirmation, which is generally outside the scope of the WPA’s protections (as well as those of the ICWPA and MWPA). Nor did Sondland have a protected government position to fall back on. Meanwhile, NSC positions, unlike many other White House positions, have generally been filled using “Schedule A” excepted service hiring authorities, which would place them within the WPA’s scope. This means that the termination of the Vindmans may well trigger WPA protections. That said, it’s also possible that Trump or his predecessors had previously determined that these positions must be excluded from the WPA’s protections under the “conditions of good administration” exception or that at-will termination was incorporated into the terms for such positions, both of which may complicate the application of WPA protections. Either way, because the Vindmans were detailed military personnel, they will return to career positions that fall within the scope of the MWPA, protecting them from further repercussions.

If the Trump administration were to attempt to pursue a prohibited personnel action against covered individuals—or has already done so in removing the Vindmans—this would almost certainly result in a legal fight. Each whistleblower statute allows protected individuals to challenge any adverse personnel action before various internal administrative procedures, where they can seek to reverse the action, receive compensation and secure sanctions against their offending supervisors. The WPA also provides an individual cause of action that protected employees can use to challenge administrative determinations in federal court. Regardless of the venue, the focus of any such debate is likely to be whether the affected employee had grounds under the WPA to “reasonably believe” that he or she was discussing evidence of an “abuse of power” or “violation of law or regulation”—requiring the adjudicating body or court to pass judgment on Trump’s own conduct and the other actions observed by the employee. This would be an ironic and potentially damaging inquiry for the Trump administration to initiate so soon after the president’s acquittal by the Senate.

Alternatively, the Trump administration could try to argue that the various whistleblower laws are unconstitutional on grounds similar to those deployed against the Lloyd-LaFollette Act. This would be a major departure from prior administrations, which largely accepted the constitutionality of whistleblower protections and even urged their adoption and reinforcement.

Of course, the Trump administration has not been shy about departing from the legal positions of its predecessors—especially when it comes to defending the president against accusations of misconduct. Yet even this position is likely to be an uphill battle. The government would first have to successfully argue that its directive not to cooperate with the impeachment inquiry superseded long-standing agency policies and regulations guaranteeing whistleblower rights—a difficult argument to make.

Even then, aside from classified information (which is not at issue in the impeachment proceedings), the executive branch’s core objection to the broad disclosures authorized by the Lloyd-LaFollette Act was that they would interfere with the president’s authority to regulate the flow of “privileged” information in the executive branch, meaning that subject to executive privilege. So constitutional objections are likely to come down to whether the disclosures protected by the whistleblower statutes fall within the scope of executive privilege. Relevant case law, however, confirms that executive privilege is a qualified privilege that has to be weighed against other public interests, and strongly suggests that it should generally yield where “there is any reason to believe government misconduct occurred”—the same basic touchstone as the whistleblower statutes. No doubt this informed prior administrations’ positions supporting the constitutionality of the current scope of the whistleblower statutes. In the case of the impeachment witnesses, this means that resolving any constitutional challenge may require the courts to rule on whether the affected employees had reason to believe misconduct had occurred, putting the conduct of the president and his allies once again at the center of the inquiry. Again, this seems like an outcome Trump and his allies would be advised to avoid.

None of this is reason to understate the fear that those federal employees who participated in the House’s impeachment proceedings may be feeling, or to look past the incredible pettiness and impropriety of Trump’s reprisals. Nor are the whistleblower statutes airtight, as there are countless small ways that Trump and his allies may be able to make witnesses’ careers in government less palatable that are difficult to prove or simply do not rise to the level of punishable conduct. And Trump may well choose to push the statutes’ limits, in spite of the possible legal and political consequences. While the law can help shield civil servants from flagrant abuses, it can’t completely insulate them from a president determined to punish them. This is why testifying as part of the House impeachment inquiry was such a brave act—and why the civil servants who did so deserve to be protected.