Legal Tetris and the FBI’s ANOM Program

It turns out that running a fake encryption company leaves a lot for the lawyers to sort out.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

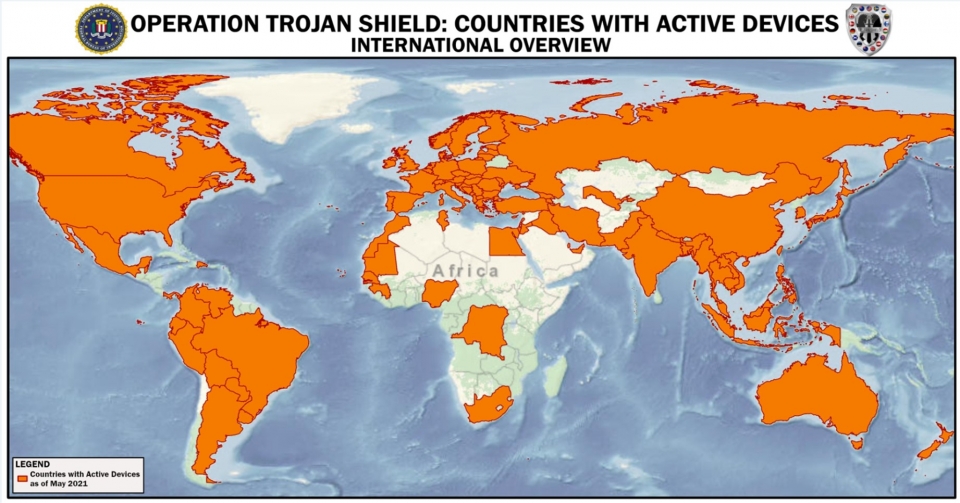

On June 8, the Department of Justice, in conjunction with the law enforcement agencies of several partner countries, announced hundreds of arrests that began in Australia and spread across Europe in what the department described as an “investigation like no other.” The arrests were the culmination of a years-long transnational operation, known to federal law enforcement as Operation Trojan Shield. As part of the operation, the FBI set up a company to offer what it billed as communications security to criminals, but actually offered the bureau a way into criminals’ phones. The company, called ANOM, distributed 12,000 encrypted phones to members of almost 300 criminal syndicates across the globe. Because every encrypted message sent from an ANOM device carried the information needed to decrypt it, the FBI and other law enforcement agencies were able to monitor all communications on ANOM’s devices.

The experiment succeeded. According to the department’s announcement, Operation Trojan Shield saw “800 arrests; and seizures of more than 8 tons of cocaine, 22 tons of marijuana, 2 tons of methamphetamine/amphetamine; six tons of precursor chemicals; 250 firearms; and more than $48 million in various world wide currencies”—not to mention dozens of newly opened public corruption cases and the closure of more than 50 drug labs. A grand jury indictment arising from the ANOM program, for example, charged 17 foreign nationals (eight of whom have been arrested) with violating both the Racketeering Conspiracy to Conduct Enterprise Affairs (RICO Conspiracy) and criminal forfeiture law.

But it turns out that running a fake encryption company leaves a lot for the lawyers to sort out. Now that the surprise of the initial arrests has worn off, we thought it worth taking time to parse through some of the legal problems that the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of California had to solve as they ran Operation Trojan Shield. It’s a complicated program that merits some untangling. On the whole, the ANOM program stands up well from a legal and policy standpoint, despite the complexity and innovativeness of its legal framework. At the same time, the features that made it successful and relatively uncontroversial, particularly the pervasive criminality of the entire customer base, put real limits on how often this tactic can be used with success.

First, the details of the operation. According to the unsealed search warrant application, Operation Trojan Shield began around 2018 after the FBI arrested Vincent Ramos. Ramos was the CEO of a company called Phantom Secure, which sold “hardened encrypted devices” to criminal organizations. The devices were essentially mobile phones with remarkably limited functionality. Users couldn’t make normal calls or browse the internet; in fact they could only communicate to a “self-selected closed group of individuals using only other Phantom Secure Devices.” In order to purchase a device, “would-be users needed to have a connection to a known distributor.” In other words, a potential buyer needed a criminal connection to “even begin the initial conversation to obtain a device.”

Ramos was ultimately arrested and pleaded guilty to RICO violations and other crimes. In pleading guilty, he admitted that Phantom Secure “(1) aided and abetted the importation, exportation, and distribution of illegal drugs throughout the world; (2) obstructed justice through the destruction and concealment of evidence from law enforcement; and (3) laundered drug trafficking proceeds.” His departure from the scene left a hole in the market, and the FBI was able to recruit a confidential source who was working on the “‘next generation’ encrypted communications product.” The source, who had distributed Phantom Secure and another company’s encrypted devices, agreed to let the FBI take control of the next generation device, called ANOM, in the hope of getting a reduced sentence for other federal crimes. The source agreed to distribute ANOM devices by tapping into an “existing network of distributors of encrypted communications distributors, all of whom have direct links to [transnational criminal organizations].” The affidavit implies that ANOM borrowed the “invitation only” distribution system of Phantom Secure, requiring the distributors of these devices to vet potential buyers, usually through “either a personal relationship or reputational access … premised on prior/current criminal dealings.”

It looks as though the FBI had settled on a marketing strategy not unlike, say, the early stages of Silicon Valley successes such as Clubhouse or even Gmail. ANOM relied on “influencers,” who played a role similar to social media influencers—except that they were “well-known crime figures” who “have a tremendous impact on users adopting specific hardened encrypted devices.” You couldn’t get the device unless you had “either a personal relationship or reputational access with a purchaser premised on prior/current criminal dealings.” From a marketing point of view, this gave the ANOM app buzz and cachet, plus it had an air of added security—presumably the police would have trouble getting invitations.

From a legal and moral point of view, this strategy paid dividends to the FBI. First, because the point of the app was to allow government surveillance of communications, having the app accidentally take off among businessmen or human rights campaigners would raise moral questions. And, as we can see from the indictment, the Justice Department used the invitations-for-criminals-only recruitment process to treat ANOM like one giant RICO enterprise—in essence, a single sprawling criminal conspiracy. RICO and conspiracy law are almost absurdly friendly to prosecutors. Criminal defendants don’t have to know the full scope of the criminal conspiracy, or most of the conspirators, to be prosecuted for joining it. They just need to agree with one other party to do something that furthers the enterprise. In the words of the Justice Department’s Criminal Resource Manual, in order to find someone guilty of violating the RICO statute under the “more expansive view” of U.S. v. Phillips:

the government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt: (1) that an enterprise existed; (2) that the enterprise affected interstate commerce; (3) that the defendant was associated or employed by the enterprise; (4) that the defendant engage in a pattern of racketeering activity; and (5) that the defendant conducted or participated in the conduct of the enterprise through a pattern of racketeering activity through the commission of at least two acts of racketeering activity as set forth in the indictment.

And as the ANOM indictment would eventually frame it, the purpose of this criminal enterprise was to “create, maintain, use, and control” a secure method of communication.

Stripped of the prosecutorial verbiage, this means that everyone who bought and used an ANOM phone was automatically a part of the criminal enterprise. This was remarkably convenient for federal law enforcement. Need probable cause to search an ANOM user? He’s a subscriber, and that’s probable cause that he’s part of the criminal conspiracy to use ANOM phones. Need a wiretap order? Most of the facts that are usually hard for police to gather—probable cause that the suspect is committing a crime, that communications about the crime can be obtained through interception, that other investigative methods are unlikely to work, that the tapped facilities are being used by the suspect—can be pulled right off the subscriber’s application form to join ANOM.

After the ANOM source agreed to cooperate, the FBI opened Operation Trojan Shield with the Australian Federal Police (AFP) and other partner law enforcement agencies. As the affidavit notes, the FBI’s confidential source “built a master key” into the ANOM device’s “existing encryption system which surreptitiously attaches to each message and enables law enforcement to decrypt and store the message as it is transmitted.” This meant that law enforcement was essentially blind carbon-copied (BCC’d) on each message sent from an ANOM device.

Perhaps not wanting to deal with the U.S. privacy laws during a proof-of-concept round, the FBI and the AFP carried out a “beta test” of ANOM devices. For the AFP, this was apparently an opportunity to try out a controversial new Australian authority. The Australian Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment (Assistance and Access) Act 2018 (TOLA) allows government agencies to issue “technical assistance” and “technical capability” notices to providers of communications services. The notices require that the providers give the authorities help in conducting criminal enforcement intercepts, and that they make changes in their systems to ensure that they can give that help. The law has significance outside Australia as law enforcement agencies in Western democracies have been seeking authority to set limits on end-to-end encryption services. And TOLA represents a high-water mark for those efforts.

In future cases, most private communications providers in Australia will perhaps seek to fight over the scope of their obligations under TOLA. But here, the human source, who was distributing ANOM devices, did not have any incentive to fight such notices. Using ANOM for an early TOLA order was the law enforcement equivalent of opening a Broadway show in New Haven for a night. The commissioner of the AFP, Reece Kershaw, has confirmed that Australian police used authorities under TOLA for the ANOM operation, but it is not clear precisely what authorities the AFP used. At an initial guess, based on publicly available documents, it appears that this was a technical capability notice that justified modification of the existing ANOM system so that a master encryption key was surreptitiously transmitted with each message. If so, the AFP may need to brace for tough reviews in New Haven. They’ll have to explain why adding a master key to every message comports with TOLA’s ban on “build[ing] a systemic weakness, or a systemic vulnerability, into a form of electronic protection.”

For the test round in October 2018, the confidential source distributed about 50 ANOM devices to “three former Phantom distributors with connections to criminal organizations, primarily in Australia.” The AFP secured a court order to monitor the devices, an order that “did not allow for the sharing of the content with foreign partners.”

The initial beta test was a resounding success. As the affidavit notes, Australian law enforcement reported that “100% of Anom users in the test phase used Anom to engage in criminal activity,” thus bolstering the “ANOM is a criminal enterprise” narrative. Using the tool, the AFP was able to penetrate “two of the most sophisticated criminal networks in Australia.” The source also saw an increased demand for ANOM devices “inside and outside of Australia.” Following the beta test, the number of devices grew steadily as the distributors continued to market the devices as, in the words of the indictment, “designed by criminals for criminals.”

Despite this initial success in Australia, the FBI was “not yet reviewing any of the decrypted content of ANOM’s criminal users,” probably because the Australian intercept order didn’t allow for sharing with foreign agencies. In any event, the FBI chose a curiously roundabout way of getting access to ANOM messages. For ANOM devices operating outside of the United States, “an encrypted [blind carbon copy or BCC]” of each message that a user sent was transmitted to a server located outside of the United States, which then decrypted and reencrypted the message with an encryption key known to the FBI. Those reencrypted messages were sent to another server that was owned by the FBI, outside of the United States.

In the summer of 2019, the FBI started negotiating to build the legal structure that would make this technical architecture work. In essence, the FBI went looking for a third country that would host the BCC server and could lawfully accept all of the decrypted messages and send the copies to the FBI. As the affidavit notes, “Unlike the Australian beta test, the third country would not review the content in the first instance.” This would have been a fascinating negotiation. Both participants wanted to make criminal cases and avoid privacy scandals. The U.S. would want to be sure that the third country had full legal authority to intercept the contents of every ANOM message, and that the country was also willing to share the full ANOM take with the U.S. in something like real time. It’s fair to assume that the third country had the authority for an intercept. (We’d argue that the U.S. did too, but it might have had to get separate orders for every phone and every suspect; finding a country with a less cumbersome process would be a big time saver.)

It wouldn’t be hard for the U.S. to persuade a third country that it wanted the full take from the ANOM criminal phone system. For any country, sharing personal data, even the data of crooks, with the U.S. is a guaranteed privacy flap, and most countries would not be willing to get creative about how to do that. But one thing makes this situation different: Without the FBI’s decryption assistance, the third country had no access to the system, ANOM was literally a black box, and communications on ANOM phones were as unreadable to the third country as those on WhatsApp or Signal. The FBI had the high card. It could hand the third country a massive criminal intelligence windfall if that country found a way to share the intelligence back to the FBI. And in the end, the FBI found a third country that was able to get creative, agreeing to get a court order to send intercepted and decrypted messages to a server where they’d be copied and sent to the FBI without prior review under a mutual legal assistance treaty, or MLAT. MLATs usually entail the assisting country collecting and turning over evidence that it has vetted, so the decision not to review the contents of the server beforehand shows just how strong the FBI’s hand was.

To make sure that it could not be accused of laundering the intercept of U.S. person communications through a third country’s legal regime, the FBI “geo-fenced” U.S. users, so that any ANOM device with a U.S. mobile country code (MCC) was routed away from the server to which the FBI had access. But to make sure the FBI was not blinding itself to imminent criminal activity inside the U.S., messages sent from inside the U.S. were reviewed by the AFP “for threats to life based on their normal policies and procedures.” According to the Justice Department’s press release, throughout Operation Trojan Shield, “over 150 unique threats to human life were mitigated.” The “threat to life” standard echoes the provision of U.S. law that allows communications providers to share user data with law enforcement without legal process under 18 U.S.C. § 2702. Whether the AFP was relying on this provision of U.S. law or a more general moral imperative to take action to prevent imminent threats is not clear.

The main operation ran from October 2019, when the third country began providing the FBI with data from its server until that country’s string of court orders expired on June 7, 2021. In total, the FBI catalogued more than 20 million messages from about 12,000 devices in more than 90 countries. The eight U.S. defendants already arrested are probably enough to ensure that there will be a legal challenge to the operation and a stream of further details as the proceedings wear on. But based on what we’ve seen so far, we like the Justice Department’s chances in court.

If the program succeeds, perhaps the Justice Department and the FBI will take what seems to have been the brainchild of a few San Diego lawyers and agents and turn it into a long-term program, guaranteeing that crooks can never again trust even the most expensive and exclusive phone security system.

They’ll have to rely on Signal and WhatsApp like the rest of us.

-(1)-(1).png?sfvrsn=1bc11cd_4)

_-_flickr_-_the_central_intelligence_agency_(2).jpeg?sfvrsn=c1fa09a8_5)