Life and Times of a Guantanamo Detainee

Guantanamo Diary

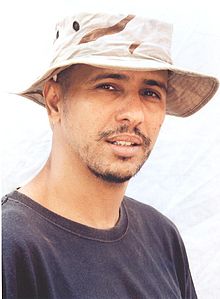

By Mohamedou Ould Slahi (edited by Larry Siems)

Published by Hatchette Book Group (2015)

Reviewed by Zoe Bedell

It's rare that quotes on the back of a book tell you anything genuinely useful about the book, but the blurbs for Guantánamo Diary are, in fact, remarkably revealing.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Guantanamo Diary

By Mohamedou Ould Slahi (edited by Larry Siems)

Published by Hatchette Book Group (2015)

Reviewed by Zoe Bedell

It's rare that quotes on the back of a book tell you anything genuinely useful about the book, but the blurbs for Guantánamo Diary are, in fact, remarkably revealing. Glenn Greenwald kicks off the show with a vaguely hysterical warning about “the future of our democracy.” Anthony Romero of the ACLU makes a thoughtful comment about the book's disturbing story, the resilience of the human spirit, and the importance of human rights. Fiction writer John le Carré compares the book to the works of Orwell and Kafka. And reporter Carol Rosenberg of the Miami Herald offers a cold recitation of the facts.

And in fact, the “diary” of Guantánamo detainee Mohamedou Ould Slahi is all of these things at different times (and occasionally at the same time): vaguely hysterical, oddly touching, and a sometimes confusing blend of fact and fiction. The only thing missing from the back of the book is an unrelenting assertion of the author’s innocence. Maybe the blurb writers thought Slahi had that more than adequately covered on his own. Or perhaps even Glenn Greenwald was not prepared to go that far.

Guantánamo Diary is Gitmo detainee Slahi’s version of his story, with a little help from journalist/activist Larry Siems. Slahi (though of course he maintains his own innocence) has been accused of recruiting the individuals responsible for the September 11 terrorist attacks. I put “diary” in quotes above because Slahi wrote the story by hand from his cell in Guantánamo (where he remains today) after his detention situation had improved markedly, rather than as the story was unfolding. (Slahi explains his improved situation as the Americans finally realizing that he was innocent all along. That’s one explanation. The American government has a different one.) But even if the story isn’t pure “in-the-moment” insight (and not just because the U.S. government has redacted some of the potentially most interesting parts), it’s still one of the only first-hand accounts we have from Gitmo, and a highly engaging one at that.

Siems starts the book off with a brief introduction in his own voice, and then Slahi’s story begins with his rendition from Jordan to Afghanistan in July 2002, and on to Guantánamo Bay. This is almost a teaser, letting us know what’s to come: Slahi introduces us to his story and some of the basics of what he experienced in American detention. It is also our introduction to Slahi’s voice, which is almost without fail thoughtful and funny.

The story then jumps back in time to Slahi’s first arrest in Mauritania and his progression through the Mauritanian, Jordanian, and ultimately American detention systems. According to Slahi, the Americans have apparently accused him of a variety of crimes, none of which is supported by evidence. The U.S. government’s story here would no doubt be a bit different: the government has maintained that Slahi helped recruit the 9/11 hijackers and provided al-Qaeda with other material support. Slahi reminds us (repeatedly) that he turned himself in to the Mauritanian authorities for questioning; though he claims they eventually came to believe he was innocent, they had no choice, he says, but to cooperate with the Americans. Same story with the Jordanians — and although his encounters with their detention and interrogation system were noticeably less voluntary, he still believes the experience vindicates his innocence. Though the Jordanians were known (and really, selected by the Americans) for their harsh interrogation techniques, Slahi never alleges he was tortured in their hands, because, according to his account, the Americans never provided the Jordanians with enough evidence to justify it.

Eventually, according to Slahi, the Americans realize they’re going to have to do the job themselves, and so Slahi is shipped to Bagram and ultimately on to Gitmo, where he arrives in August 2002. While the trip to Cuba was clearly physically and psychologically unpleasant, his initial experience in Gitmo is primarily one of endless and repetitive interrogation. As Slahi refuses to tell the interrogators what they wanted to hear (again, according to him), they begin to use tactics like leaving Slahi in an extremely cold cell and sleep deprivation; as they use harsher tactics, Slahi becomes more uncooperative, refusing to speak at all during his sessions. At various points, Slahi attempts to negotiate for his cooperation, promising he will cooperate fully if the interrogators will just tell him what charges they’re holding him on. According to Slahi, the interrogators were never able to answer.

Eventually, around June 2003, Slahi is moved into total isolation, and his treatment starts to worsen significantly. His cell is kept consistently cold, and he is provided only a thin iso-mat and blanket; all other possessions, from his Koran to his soap, are taken away. During interrogation, Slahi is knocked off his chair when he doesn’t answer questions appropriately and is forced to stand hunched over because his hands are chained to the floor, a position that is all the more difficult because of his sleep deprivation and sciatic nerve pain. The guards beat him at every opportunity between interrogations.

I’ve probably said enough times by now that these bits of the story are Slahi’s version. So, continuing: Slahi claims he is interrogated 24 hours a day; whether this is technically true, he is apparently questioned at irregular intervals throughout the day to ensure he is kept off schedule and sleep-deprived. Even when he is not in interrogation, the guards are tasked with keeping him awake. Sometimes they do this by playing “games” like requiring him to clean out his entire cell for inspection; other times, they require him to drink water constantly, so that he has to urinate regularly. This last tactic was apparently designed so that the sleep deprivation is his own doing; apparently the psychological impact of his own body keeping him awake is even greater than if the guards had achieved the same result.

This period is also allegedly when the sexual molestation begins. Slahi’s descriptions here are brief, lacking his normal descriptive detail and clarity, but he describes female military personnel rubbing their bodies on his, touching him inappropriately through his clothes, talking dirty, and apparently even forcing Slahi to “take part in a sexual threesome.” Though the military has been previously alleged to have used sexual situations and harassment to get detainees to talk, this appears to be the first time that allegations have emerged of actual sex (to my knowledge, at least; Lawfare would be grateful for input from knowledgeable readers).

Things ramp up again in August 2003 (according to the commentary provided by Siems, this was after a special interrogation plan had worked its way through the system and had been signed off on by Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld). Slahi is “kidnapped,” or made to believe he is taken to a new, faraway, and secret location. He claims he knew all along he was just on a round-trip boat ride out to sea and then back to Guantanamo, but that likely eased the pain only a little. He is forced to drink salt water, and his clothes are stuffed with ice first to keep him cold, as well as to more quickly heal the bruises from the beatings. Slahi is eventually deposited in another cold cell, and the interrogations and beatings continue. He is told his mother was captured; he is starved, then given food but no time to eat; he is deprived of water, then forced to drink until he vomits.

It is in these sections, describing the worst interrogation techniques and the torture, that Slahi’s writing is the least clear and the most muddled and difficult to follow. His humor is gone, as are the keen observations. It’s not clear whether he has done this purposely, but it certainly appears that Slahi’s experience was so traumatizing that he has trouble writing about it even in retrospect.

Finally, he can’t take it any more. Slahi starts to cooperate, or by his telling, starts to tell the Americans the fanciful stories they want to hear. By his own admission, he provides reams and reams of information and details; the interrogators even give him a laptop so he can write faster. In Slahi’s version, these stories are entirely made up; as the Americans check them out, they realize they are false and conclude that he has been telling the truth from the beginning when he said he was innocent. Once the interrogators realize they have made a terrible mistake, Slahi’s situation starts to improve, and he is allowed to live a life of relative luxury. This is when he writes his manuscript. (Again, the U.S. government’s explanation for this change in circumstances is that Slahi finally began telling the truth, and was rewarded accordingly.)

But as Slahi’s life arc improves, so does the quality of his story, returning to the wit and charisma he displayed at the beginning. He transitions easily from detailed accounts of his experience, to wry observations on his situation, to broader ruminations on justice and human nature. This can be difficult for anyone to do well, and given that Slahi is in some ways an unreliable narrator (not to mention an accused recruiter of the 9/11 hijackers) and writing in his fourth language, the odds don’t seem to stack up in his favor. But for the most part, he keeps his observations short, sharp, and devastatingly insightful.

For example, in recounting how he dealt with cruel guards in Bagram by pretending he didn’t understand English, Slahi summarizes his situation this way: “People with hatred always have something to get off their chests, but I wasn’t ready to be that drain.” It’s a resiliently wry line – so much so, I half expect it to show up one of these days in an anti-bullying video for teenagers on YouTube. In another passage, discussing persecution and false arrests in America, Slahi quotes a German proverb: “Today Them, Tomorrow You!”

Some of his attempts at this sort of commentary fall short. At one point, Slahi asserts with doe-eyed innocence that he “believe[s] simply that an innocent suspect should be released.” Of course, the reader can’t disagree, and that is the point; nonetheless, the implication that he is that innocent suspect deserving release is a bit tough to swallow. But despite the occasional miscues, I often found myself nodding along in rueful agreement with some of his keener observations.

After the section recounting his torture, Slahi devotes an entire section to discussing and describing his guards and interrogators. As might be expected, the U.S. government took its shot at (inconsistently, and often bizarrely) redacting the manuscript before it was handed over to Slahi’s lawyers, and those redactions make this part a bit hard to follow; it is nonetheless one of the most compelling parts of the book. Though Slahi describes jerks and cruelty, he also describes kind people with whom he apparently formed genuine bonds. His description of his relationship with one female interrogator in particular depicts apparent mutual respect and affection, such that both are deeply saddened when she is transferred at the end of her assignment. Slahi asks himself the questions that no doubt go through the readers’ minds, wondering how he could develop compassionate feelings for these people who made his life hell. His answer is an extended comparison between himself and a slave:

Slaves were taken forcibly from Africa, and so was I. Slaves were sold a couple of times on their way to their final destination, and so was I. Slaves suddenly were assigned to somebody they didn’t choose, and so was I. And when I looked at the history of slaves, I noticed that slaves sometimes ended up an integral part of the master’s house.

It’s not clear if these touching descriptions should be considered more or less reliable than any other part of the book. Sometimes they are harder to believe.

Slahi is also funny. He opens Chapter two with a Mauritian folktale about a mentally ill man who is deeply afraid of roosters:

“Why are you so afraid of the rooster?” the psychiatrist asks him.

“The rooster thinks I’m corn.”

“You’re not corn. You are a very big man. Nobody can mistake you for a tiny ear of corn,” the psychiatrist said.

“I know that, Doctor. But the rooster doesn’t. Your job is to go to him and convince him that I am not corn.”

The man was never healed, since talking with a rooster is impossible. End of story.

For years, I’ve been trying to convince the U.S. government that I am not corn.

Whether or not you think Slahi is corn (or just plain corny), it’s a great chapter opener.

Siems’s work on the book should be mentioned as well. He provides line-by-line edits to clean up Slahi’s grammar and has occasionally consolidated text. He also made more substantive changes that re-ordered parts of the “diary,” including incorporating flashbacks into the rest of the story and otherwise streamlining Slahi’s original manuscript from 122,000 words to 100,000 words.

But most helpfully, Siems has annotated the manuscript. Sometimes these annotations are to guide the reader through the story and the characters, which is sometimes difficult to follow given the redactions. These annotations are generally very helpful; though the book is surprisingly readable even with the redactions, when Slahi starts relating conversations, or describing all of his guards, the black boxes would be more confusing without Siems’ help.

Siems has also added some footnotes that apparently verify elements of Slahi’s story, often by pointing the reader to external sources that either confirm time-frames or fact patterns. Many of the footnotes point us to external reports prepared by agencies such as the Senate Armed Services Committee, DOD, or the DOJ that verify various aspects of the story. These are helpful; it’s impossible to forget first, that you are reading one person’s version of his own story and second, that he is somewhat suspect (and that’s a generous assessment) as a reliable narrator. These references serve as small confirmations of instances where Slahi’s account has been externally verified, and help drive home what for many is and should be one of the main takeaways of this book: the vivid portrait of the interrogation techniques practiced at Guantánamo Bay.

What’s missing, though, are the footnotes telling us where we should take the story with a grain of salt. Siems tells us in the introduction that a D.C. district court ordered Slahi released — but does not mention that the D.C. Circuit vacated that opinion. Siems mentions that the military prosecutor assigned to Slahi’s case declined to bring charges and withdrew from the case on moral grounds — but does not mention that the prosecutor also fully believed that Slahi was guilty. Ben Wittes has provided a helpful summary of the alternate view of who Slahi is, and anyone looking to form a balanced view will need to read it, or some other external report. Siems’s annotations are helpful, but only as far as they go and, as noted, are less than the full story.

So what the book offers is a fascinating, but definitely one-sided, account of American detention and interrogation operations from a particular and very controversial period following 9/11. The book is not the full Guantánamo story, but it’s one of the more interesting representations of this side of the story that you’re going to find. This was one of the two roughest interrogations conducted at Guantánamo, so it should not be extrapolated that this is how everyone was treated. But it’s nonetheless a side of the story that should be understood and internalized for Americans to begin to understand what the cost of the war on terror really is.

Again, the back cover provides the insights we need to summarize the book. I’m not sure if he meant to be positive, negative, or purposely ambiguous, but the vagueness of 60 Minutes correspondent Steve Kroft’s blurb perhaps provides the best snapshot: “This is an incredible document, and one hell of a story.”

(Zoe Bedell is a student at Harvard Law School and a Lawfare Contributor.)