L.M.-M. v. Cuccinelli: Trump’s Preference for Acting Officials Hits A Wall

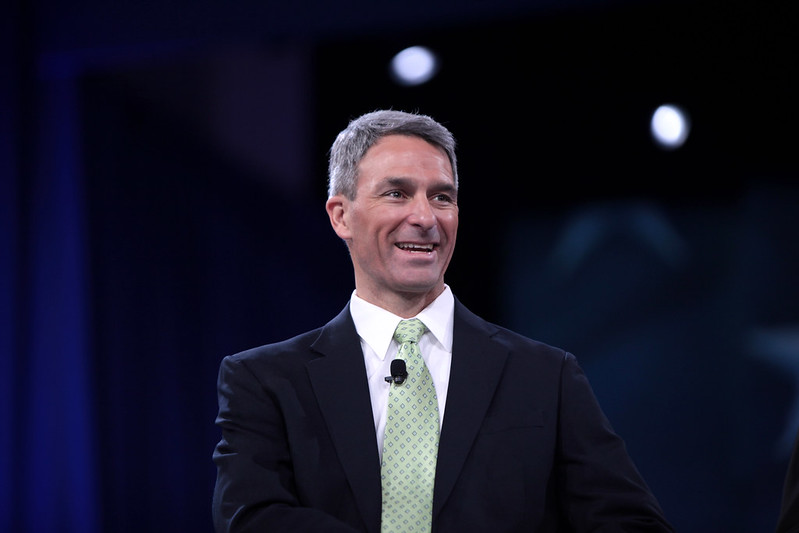

A recent challenge to a set of directives issued by then-Principal Deputy Director of USCIS Ken Cuccinelli led a federal district judge to hold that Cuccinelli’s appointment violated the Federal Vacancies Reform Act.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

For the better part of a year, the Trump administration tried without success to install the controversial former attorney general of Virginia, Ken Cuccinelli, in a high-ranking position at the Department of Homeland Security, even though the president’s allies in the Senate signaled that Cuccinelli would not be confirmed if nominated. In June 2019, the administration thought it had finally found a way. Then-Acting Secretary of Homeland Security Kevin McAleenan first created an entirely new position at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the “principal deputy director.” He simultaneously changed USCIS’s line of succession to provide that the new principal deputy director—rather than the existing deputy director, a career senior executive named Mark Koumans—would serve as the second-in-command, or “first assistant,” to the director. And finally, he appointed Cuccinelli to serve as the principal deputy director (without even nominating anyone as director).

The upshot of all these procedural machinations was that Cuccinelli purported to ascend immediately to become the acting director of USCIS under the Federal Vacancies Reform Act (FVRA)—the law that generally determines who may serve as an acting official—even though he’d never served in the federal government, in any capacity, not even for a day.

On March 1, however, a challenge by asylum-seekers and a legal services organization to a set of directives issued by Cuccinelli led a federal district judge to hold in L.M.-M. v. Cuccinelli that Cuccinelli’s appointment as acting director “cannot be squared with the text, structure, or purpose of the FVRA” and thus was invalid, as were the directives he ordered. And the court’s decision most likely means that other policies issued with Cuccinelli’s involvement are similarly invalid.

Yet Cuccinelli is far from the only acting official that the Trump administration has tried to install in the federal bureaucracy. According to the New York Times, “[o]f the 75 senior positions at the Department of Homeland Security, 20 are either vacant or filled by acting officials, including Chad F. Wolf, the [current] acting secretary.” To the extent any of these acting officials are similarly serving unlawfully under the FVRA, any policies in which they have been involved could also be rendered invalid. Such a result would have major ramifications for the Trump administration’s policy agenda, all because it chose to abuse the FVRA in order to bypass the Senate.

Background on the Lawsuit

On Sept. 6, 2019, seven asylum-seekers and the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services filed suit to challenge three directives issued by Cuccinelli that limit asylum-seekers’ rights: a directive cutting the amount of time asylum-seekers have to consult with their attorneys before their critically important “credible-fear” interviews from 48 to 24 hours or less, a directive preventing asylum-seekers from obtaining continuances of that time except in the most extreme of circumstances, and a directive ending an in-person legal orientation program used at some detention facilities to ensure asylum applicants were aware of their legal rights.

Alongside other claims, the plaintiffs challenged Cuccinelli’s appointment under the FVRA. Enacted in 1998, the FVRA provides the president with limited authority to appoint acting officials while preserving the Senate’s advice-and-consent power—a power that serves as “a critical ‘structural safeguard [] of the constitutional scheme.’” The act stipulates that an individual may serve as an acting official in a position requiring Senate confirmation only if they’re the “first assistant” to the vacant position, they’ve been confirmed by the Senate for another position or they’ve served in the federal government for a sufficient period of time. The FVRA contains a powerful enforcement mechanism: Any actions taken by an improperly appointed acting official in the performance of the functions or duties of the office “shall have no force and effect” and “may not be ratified.”

The plaintiffs’ primary argument under the FVRA was that an individual can serve as an acting official in a position only if they were named first assistant before that position became vacant. This is consistent with the FVRA’s text, which says that, if an officer “dies, resigns, or is otherwise unable to perform the functions and duties of the office,” then “the first assistant … shall perform” the duties of the office, and thereby provides what the Supreme Court characterized in Southwest General as a “mandatory and self-executing” procedure for immediately filling a vacancy with the first assistant at the moment the office becomes vacant. If the president or an agency head could name a first assistant after the vacancy arose, as in Cuccinelli’s case, they could effectively hand-pick anybody they wanted, regardless of whether that person has been confirmed by the Senate or served in the federal government for any length of time—rendering those other provisions of the FVRA meaningless. It would also vitiate the Senate’s advice-and-consent powers and cannot be squared with Congress’s ultimate goal in passing the FVRA: to limit the president’s power in making acting appointments.

During oral argument on the plaintiffs’ preliminary injunction motion, the court asked probing questions about why it wouldn’t “eviscerate” the FVRA for an agency to, as happened here, “create a new position of super first assistant” in order to skip over the official who would have otherwise filled the position. As the court noted, “[i]f you can do that, then it seems like the [FVRA] was a waste of an effort.” By consent of the parties, the court converted the preliminary injunction briefing to cross-motions for summary judgment.

The Court’s Decision

On March 1, the court granted in part and denied in part both sides’ cross-motions for summary judgment. On the merits, the court held that Cuccinelli’s appointment as acting director of USCIS was unlawful but did not address whether, in general, a first assistant must be appointed before a vacancy to fill it on an acting basis. Instead, the court relied on a somewhat narrower version of the plaintiffs’ argument—one grounded in precisely how radical and flimsy the government’s attempt to appoint Cuccinelli was. Specifically, the court explained that the fact that the position of principal deputy director was slated to dissolve as soon as a USCIS director was confirmed by the Senate meant that Cuccinelli’s “appointment fails to comply with the FVRA for a more fundamental and clear-cut reason: He never did and never will serve in a subordinate role—that is, as an ‘assistant’—to any other USCIS official.” He therefore could not serve as the acting director under Section 3345(a)(1).

In reaching that conclusion, the court focused on “the essential meaning of the word ‘assistant,’ which under any plausible construction comprehends a role that is, in some manner and at some time, subordinate to the principal.” The court was persuaded, in part, by the unprecedented steps undertaken here to install Cuccinelli and found

no evidence that at any time prior to Cuccinelli’s appointment did Congress or the Executive Branch imagine that an agency could create a new position after a vacancy arose; could then alter the agency’s order of succession to treat that new position as the “first assistant” to the vacant office; and could further specify that all would return to its original state once the … vacancy was filled.

The court also reasoned that “[d]efendants’ reading of the FVRA would decimate [its] carefully crafted framework,” under which the president alone can select acting officials and only if they possess the qualifications required by the FVRA.

Turning to the proper remedy, the court explained, quoting the FVRA, that “[u]nder the FVRA’s vacant-office provision, if a person is not lawfully serving in conformity with the FVRA, ‘[a]n action taken’ by that person ‘in the performance of any function or duty of [the] vacant office … shall have no force or effect’ and ‘may not be ratified.’” The court noted that defendants did not dispute that the power to establish policies for the nation’s lawful immigration system is specifically vested in the director. Instead, defendants claimed that there were effectively no functions or duties specifically vested in the USCIS director—or anybody else at Homeland Security—because the department’s organic statute vests all functions in the secretary, who may then delegate them to subordinates. The court rejected that extraordinary position, explaining that it did not merely conflict with parts of the FVRA’s enforcement scheme but would nullify that scheme completely, given that virtually every agency has a similar provision in their organic statute. The court also identified a further reason to set aside policies enacted by unlawful acting officials: Such policies aren’t issued “in accordance with law,” as the Administrative Procedure Act requires.

The court therefore held that the reduced-time and extension-limiting directives were unlawful and had to be set aside. (The court held that the third directive had not been reduced to writing and therefore was not reviewable under the expedited removal statute.) The ruling had immediate impact: Because the asylum-seeker plaintiffs had been subjected to unlawful procedures during their credible-fear interviews, their resulting negative credible-fear determinations and removal orders had to be set aside, providing them with an opportunity to reinterview under the former procedures. In addition, the court’s order means USCIS may not use those directives moving forward. And the FVRA’s prohibition on ratification means USCIS cannot simply readopt them.

The morning after the court issued its order, Cuccinelli gave an interview on one of the president’s favorite television shows, “Fox & Friends,” where he asserted that the directives would be “effectively reissued and validated … as a precautionary measure while an appeal goes forward.” As of this writing, and as far as we’re aware, the government has not attempted to ratify or reissue the directives that were set aside. Nor has it filed an appeal. However, the court recently entered partial final judgment on the FVRA claim as to the individual plaintiffs, so an appeal may be forthcoming.

Potential Implications

The court’s reasoning necessarily calls into question other actions taken by Cuccinelli, USCIS and Homeland Security as a whole, although the court did not have occasion to address the effect of its FVRA holding on any other policies. Nor did the court have occasion to consider whether the administration could adopt again any of Cuccinelli’s now-suspect actions. Nevertheless, the underlying legal problem identified by the court could pose an issue for other USCIS policies.

First and foremost, any asylum-seeker processed and ordered removed under the directives invalidated by the court could potentially seek to set aside their orders of removal and obtain a rehearing. If the directives were unlawful as to some asylum-seekers, they should be unlawful as to all. That said, the court’s order did not by its own force set aside orders of removal for anybody but the named plaintiffs, and some such claims may have to overcome jurisdictional or other procedural arguments seeking to limit the extent to which an order of removal may be challenged.

The implication of the court’s order seems equally clear for other policies implemented by Cuccinelli pursuant to the “functions and duties” of the USCIS director position. One of those “functions” is the director’s authority to craft policies for the nation’s lawful immigration system. By extension, then, any rules, policy directives, guidance documents, or other actions or decisions made by Cuccinelli could be subject to challenge and might, for the reasons articulated by the court, be “of no force and effect.” Moreover, plaintiffs could seek to challenge policies promulgated by USCIS or Homeland Security that lack Cuccinelli’s signature but were presumably subject to his approval or issued with his involvement or oversight. At least two pending cases—a challenge to Homeland Security’s public charge rule and a challenge to USCIS policies governing fee waivers—have raised Cuccinelli’s involvement in policymaking as a possible legal issue. Advocates have already begun looking for other policies that could be vulnerable.

But what if USCIS or Homeland Security preemptively move to ratify these now-suspect actions to try and clear the taint conferred by their connection to Cuccinelli? The FVRA is crystal clear on this point: Actions taken pursuant to the “functions and duties” of the USCIS director are not only “of no force and effect” but also “may not be ratified.” To the extent USCIS can reissue the policies at all, it could do so only if it commenced an entirely new administrative process—one lacking any involvement by Cuccinelli whatsoever.

More broadly, the court’s decision shows that there are real teeth to the FVRA and that advocates should consider the FVRA when attempting to hold the administration in check. The Trump administration has repeatedly used acting officials to circumvent the Senate’s advice-and-consent role and push its policy agenda—even when doing so risks hampering the nation’s response to once-in-a-generation crises, like the current pandemic. This cavalier approach to staffing the top positions in the federal government, which has long been understood to undermine the federal government’s effectiveness and accountability, can also render the administration’s actions vulnerable to legal challenge. To the extent other acting officials claim authority using the same procedural maneuver as Cuccinelli, the court’s reasoning as to the merits would apply with equal force to them. But even if they use some other gimmick to qualify under the FVRA, the court’s reasoning as to remedy may still apply to call a broad range of their actions into question. In sum, FVRA violations—and the brinkmanship the Trump administration has engaged in with acting appointments—can carry real legal consequences.

.jpg?sfvrsn=5a43131e_9)