Making Sense of Iran and al-Qaeda’s Relationship

The arrangement can be tense and transactional, but has provided benefits for both sides.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: Al-Qaeda and Iran are strange bedfellows. Iran’s allies and proxies are often at war with al-Qaeda affiliates, but at the same time Iran hosts senior al-Qaeda leaders. Colin Clarke of The Soufan Group and Stanford’s Asfandyar Mir unpack this odd relationship, tracing its history and identifying the advantages for Tehran and al-Qaeda.

Daniel Byman

***

The nature of the relationship between al-Qaeda and Iran is one of the most contentious debates in the counterterrorism community, dividing analysts, policymakers and government officials. The stakes of establishing or disproving the relationship are considerable—meaningful state support is immensely useful to terrorist organizations, especially one being hunted by the U.S. government. Current analytic disagreements are not necessarily about whether al-Qaeda and Iran have a relationship; on that point, there is little room for doubt. But some observers argue that ideological differences and deep distrust affect the relationship to the point that it is little more than an “insurance policy” for both sides. Others swing to the opposite extreme, arguing the relationship is more akin to a deep, strategic partnership. Still others argue that the relationship is mostly tactical and falls well short of having any strategic value.

It is important to frame the relationship in its historical context with attention to its trajectory and political implications. Such an analysis suggests that al-Qaeda and Iran’s relationship has overcome conflict to generate strategic benefits to both actors.

Al-Qaeda and Iran’s Ties Under bin Laden

The relationship between al-Qaeda and Iran is neither novel nor recent; on the contrary, it is well documented through a combination of publicly available U.S. intelligence assessments, declassified al-Qaeda documents and their detailed analysis, statements and clarifications by al-Qaeda’s own leadership, and interview-based historiography. Taken together, these materials are rich and informative on the granularities of their interaction as well as on broader political questions. The overall picture that emerges is that Iran provided critical life support to al-Qaeda, especially in times of crisis for the organization, but Iranian help came with numerous strings attached. For its part, al-Qaeda has become less ambivalent about its levels of both cooperation and conflict with Iran.

The roots of the relationship can be traced to the early 1990s. At the time, al-Qaeda and Iran struck a pact that included al-Qaeda members training with Iranian intelligence operatives in Iran and Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. In the mid-1990s, after al-Qaeda moved from Sudan to Afghanistan, Iran provided al-Qaeda operatives logistical and travel support. As per the 9/11 Commission Report, “Iran facilitated the transit of al Qaeda members into and out of Afghanistan before 9/11, and … some of these were future 9/11 hijackers.” Immediately after 9/11, Iran offered to open its borders for Arab fighters wanting to travel to Afghanistan.

Following 9/11, bin Laden’s emissaries Mustafa Hamid and Abu Hafs al-Mauritani were able to negotiate a deal with Iranian authorities. (Hamid has denied being sent by al-Qaeda.) Iran provided al-Qaeda with a passageway for its fighters fleeing Afghanistan to return to their respective countries or to move on to third-party countries. Iran also provided a permissive sanctuary for al-Qaeda leaders and their families within its borders. Amid America’s intensifying worldwide counterterrorism campaign, the Iranian sanctuary enabled al-Qaeda to constitute a military council and revive important operations, though it remains unclear to what extent this facilitated al-Qaeda’s broader international terrorism campaign.

By 2003, the relationship had grown turbulent. Iran cracked down on al-Qaeda’s presence in the country. Al-Qaeda’s top leadership in Iran was moved into the controlled custody of Iranian intelligence. As per Hamid, Iran “arrested or deported around 98 percent” of Arab fighters, and according to top al-Qaeda leader Saif al-Adel, Iranian authorities “foiled 75% of [al-Qaeda] plans.” The reasons for this break are not clear from the available materials. One possible explanation is that Tehran grew perturbed by al-Qaeda’s expanding footprint in the country, which al-Qaeda operatives made little effort to conceal and which drew unwanted attention to the Iranian regime. Another possibility is that Iran was acting in support of the brief 2002 U.S.-Iran rapprochement, though that was soon scuttled.

The U.S. invasion of Iraq created valuable incentives for al-Qaeda and Iran to form an alliance, but there was no meaningful shift in cooperation between the two. Instead, sporadic low-level hostilities, occasional tactical adjustments, and constant bargaining persisted. For instance, al-Qaeda in Iraq’s anti-Shiite campaign prompted Iran to approach al-Qaeda’s top leadership for security of Shiite sites in Iraq as well as the possibility of broader cooperation. In response, bin Laden sought accommodation for al-Qaeda militants in Iran in exchange for discussion of al-Qaeda’s overall strategy in Iraq. Some level of accommodation appears to have been secured during these years, facilitating a growing logistical role of Iranian territory for transiting fighters to Waziristan.

Iran began easing some restrictions on al-Qaeda by 2007. Senior al-Qaeda leadership entrenched in Waziristan came to view Iran as a crucial passageway for “funds, personnel, and communication,” especially as U.S. drone strikes intensified. According to journalists Adrian Levy and Catherine Scott-Clark, the head of Iran’s Quds Force, Qassem Soleimani, even reached out to al-Qaeda leadership and their families and had “regular discussions” with Saif al-Adel; in one instance, Soleimani “turned up in person” to celebrate Eid with bin Laden’s sons. Yet there remained restrictions on the leadership and their families—an issue that caused bitterness among bin Laden and his senior lieutenants. This led al-Qaeda to kidnap an Iranian diplomat in Pakistan in November 2008. Through 2009, complex bargaining between al-Qaeda and Iran ensued with ample confusion and misperception about the release of prisoners. At one point in late 2009, Iran expressed interest in learning about al-Qaeda’s strategy.

By 2010—through hard diplomacy, including the release of the Iranian diplomat, assurances of nonaggression, and threats of ratcheting up anti-Iran rhetoric—al-Qaeda successfully secured the release of key members and their families in detention.

Cooperation and Conflict After bin Laden

By the time of bin Laden’s killing in May 2011, al-Qaeda’s relationship with Iran had grown less cumbersome along tactical and, to an extent, strategic lines. For one, Iran began to formalize a logistics infrastructure for the group, with active transit facilitation for its leaders, members and recruits. This significant improvement in ties was observed by the U.S. government in 2011. Then-Undersecretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence and current Deputy CIA Director David Cohen described it as “Iran’s secret deal with al-Qa’ida,” and the following year the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Iran’s Ministry of Internal Security for providing documents, identification cards and passports to al-Qaeda. In 2013, Canadian police thwarted a terrorism plot linked to al-Qaeda operatives in Iran.

The improved transit facilitation in Iran did not preclude conflict. Both sides continued to jockey for leverage. Iran sought to coerce al-Qaeda by detaining key leaders and operatives, which frustrated al-Qaeda’s leadership. In 2013, al-Qaeda kidnapped an Iranian diplomat in Yemen, and tensions escalated further when al-Qaeda carried out a bomb attack at the home of the Iranian ambassador in Yemen in 2014.

In 2015, Iran released six al-Qaeda leaders, including Abu al-Khayr al-Masri, Abu Muhammad al-Masri, Saif al-Adel, and Abu al-Qassam, in exchange for the kidnapped Iranian diplomat. Abu al-Khayr and three others traveled to Syria, where al-Qaeda’s local leadership was publicly distancing itself from al-Qaeda’s anti-U.S. agenda to prioritize its campaign against the Iran-backed Assad regime. The remaining al-Qaeda leadership in Iran was able to finesse more latitude to operate and to participate in major political decisions. Analyst Cole Bunzel observes that in the discussion over the future of al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate, which proceeded to break away from al-Qaeda, Abu al-Qassam noted that their Iran-based leaders were important to the group’s direction and that they were not in detention but were restricted from traveling out of Iran.

As per U.S. reporting in 2016, Iran continued to allow al-Qaeda’s organization to move money via Iran, as well as to shuttle personnel and resources across major conflict zones, such as Syria and Afghanistan. This appears to have continued until at least 2020, when the U.S. State Department’s country terrorism report observed: “Tehran also continued to permit an [al-Qaeda] facilitation network to operate in Iran, sending money and fighters to conflict zones in Afghanistan and Syria, and it still allowed [al-Qaeda] members to reside in the country.”

The Relationship Today

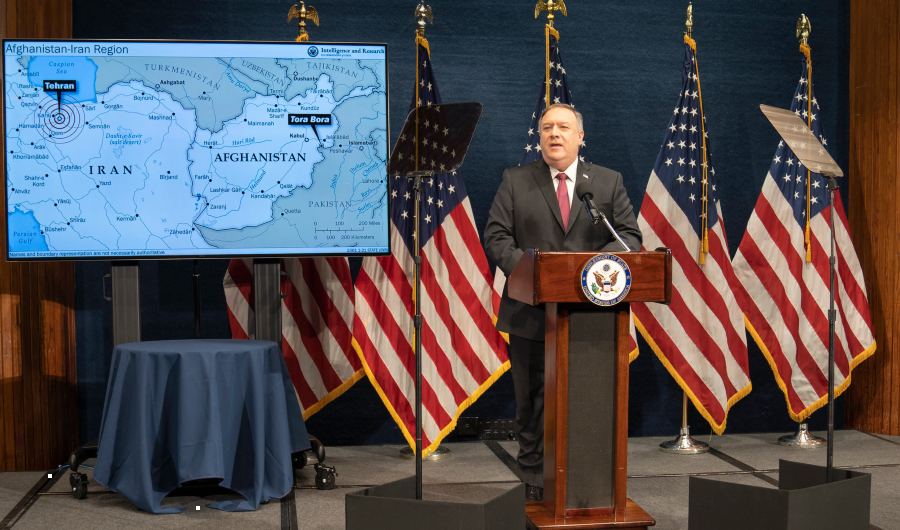

In a speech just before leaving office, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo claimed that under the guidance of deputies Saif al-Adel and Abu Muhammad al-Masri, al-Qaeda has placed new emphasis on plotting attacks from Iran. Such support would constitute a real change in Iranian behavior and ties between Iran and al-Qaeda. Pompeo went on to claim that Iran is the “new Afghanistan,” comparing it to the safe haven that al-Qaeda enjoyed in Afghanistan before 9/11, which provided it with the operational space to plan and prepare for the attacks. But Pompeo’s speech provided no evidence of operational planning in Iran, let alone a bustling infrastructure of multiple military camps with thousands of foreign fighters in training, which was the case in Afghanistan until 2001. Moreover, recent U.S. government and U.N. terrorism monitoring reports suggest that areas along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border and al-Qaeda’s powerful regional affiliates, like its East Africa branch, al-Shabab, and not Iran, are the more critical sources of threat posed by al-Qaeda.

However, Pompeo provided one crucial and novel bit of information: Senior al-Qaeda operative Abd al-Rahman al-Maghribi is alive in Iran, and in charge of coordinating with regional affiliates. Maghribi’s status is crucial. He studied software engineering in Germany before moving to al-Qaeda’s al-Farooq camp in Afghanistan in 1999; he is also the son-in-law of al-Qaeda chief Ayman al-Zawahiri and was reportedly involved in the 2006 plot to destroy multiple transatlantic aircraft. In 2010, Maghribi was based in Waziristan and in charge of al-Qaeda’s important media operation as-Sahab. At one point, al-Qaeda’s Afghanistan-Pakistan commander Atiya Abd al-Rahman wrote to bin Laden recommending his promotion as his deputy in place of Abu Yahya al-Libi due to his intellect.

Maghribi has the bona fides to assume a future leadership role, as well as more involvement in the group’s external operations. After disappearing from the battlefield of Waziristan more than a decade ago, his reappearance in Iran indicates how key al-Qaeda members have been able to survive for much longer than they would have if not for Iranian protection.

Mutual Benefit

Despite recurring friction, the relationship al-Qaeda and Iran have forged has enough cooperative dimensions to be highly beneficial for both. From the perspective of Iran, the most obvious benefit of enabling al-Qaeda to stay alive and function is that al-Qaeda refrains from attacking Iran or the Shiite populations that Iran cares about most. Al-Qaeda’s resilience helps Iran maintain equity in the global jihadist movement—without this calibration, al-Qaeda might be subsumed by the Islamic State. In a sense, this is a delicate balancing act orchestrated by Iran to prevent al-Qaeda from growing so weak that it might feel compelled into a marriage of convenience with the Islamic State. This is important for Iran on account of the Islamic State’s relentless targeting of Shiites in the region, as well as Iran’s self-image as the vanguard of Shiite Muslims worldwide.

In addition, Iran’s help to al-Qaeda to sustain its top leadership and command structure has enabled the group to continuously challenge the United States and some of its anti-Iran allies, especially Saudi Arabia. It is difficult to say whether this was the rationale for why Iran started supporting al-Qaeda and has continued to do so at various junctures since 9/11. Nevertheless, Iran reaps the benefits of al-Qaeda and its affiliates’ persistence across Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, which keeps the United States engaged and less focused on countering Iran and its expansive alliance network.

Al-Qaeda, for its part, is able to extract important and consistent material benefits from Iran, ranging from Iran’s noncooperation with the international counterterrorism regime against al-Qaeda, to documentation for transit, to facilitation of financing. These benefits are less than what Iran provides its proxies and probably resulted from sustained bargaining. But importantly, from al-Qaeda’s perspective, it would be even more challenged without the calibrated Iranian support of the past two decades, particularly given the relentless pressure of American counterterrorism outside Iran and deep hostility of Middle Eastern states to al-Qaeda. Iran’s geographic contiguity to Afghanistan and Pakistan also critically helped al-Qaeda in moving invaluable organization capital across key battlefields under direct U.S. pressure.

The most significant benefit for al-Qaeda was the safety and sanctuary of its top leaders. Despite constraints like detention during certain periods, Iranian sanctuary facilitated al-Qaeda’s longevity—and, in the process, reduced strains on overall group cohesion. If not for Iranian territory, key senior al-Qaeda operatives like Saif al-Adel, Abu Muhammad al-Masri, Abd al-Rahman al-Maghribi and Abu Khayr al-Masri would have been far more vulnerable, making their killing or capture more likely and al-Qaeda’s leadership vacuum more damaging for the group.

Implications for the Biden Administration

The Biden administration needs to be clear-eyed about al-Qaeda and Iran. Each, and the relationship between them, presents major challenges for U.S. foreign policy and national security. The relationship between al-Qaeda and Iran is complex, but its implications are highly consequential. The Biden administration should tread cautiously when weighing claims that al-Qaeda serves as a proxy for Iran, but it should also avoid discounting the support Iran has provided to the organization. As the administration works to reverse the damage of the Trump administration’s Iran policies, it will be under pressure to minimize Iran’s relationship with al-Qaeda, but policymakers must understand the mutually beneficial relationship between the two.

Al-Qaeda and Iran’s relationship is another reminder of why the Biden administration must prioritize the depoliticization of intelligence assessments and frame threats based on facts and empirical evidence. It should bring to light recent information on both al-Qaeda and Iran, and offer regular transparency on these critical issues to the American public—including through the timely presentation of the Worldwide Threat Assessment report, withheld by the Trump administration in 2020.

Most importantly, the Biden administration should clarify its stance on al-Qaeda and Iran’s relationship. This has implications not just for overall U.S. policy toward Iran but also for U.S counterterrorism policy and critical U.S. relationships in the region, including in Iraq and Afghanistan, where Washington is reassessing force posture and the nature of ongoing military commitments to both countries.