Marriage of Convenience? Liberals and the Intelligence Community Come Together Over the Russia Connection

As Americans gathered to watch James Comey testify before the Senate Intelligence Committee, a meme emerged on certain corners of the left-leaning internet: people had a crush on the former FBI director. It was his patriotism, his scrupulousness, his integrity that did it. “Get you a man who loves you like [C]omey loves the FBI,” wrote one commenter.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

As Americans gathered to watch James Comey testify before the Senate Intelligence Committee, a meme emerged on certain corners of the left-leaning internet: people had a crush on the former FBI director. It was his patriotism, his scrupulousness, his integrity that did it. “Get you a man who loves you like [C]omey loves the FBI,” wrote one commenter. “Is COMEY … attractive?” asked another. Declared one: “Comey should be the next Bachelor.”

The trend may have started with Comey, but it hasn’t ended with him. Earlier this month, Vogue reported that special counsel Robert Mueller, too, has been transformed into an unlikely object of adoration.

The point of these outbursts of affection—whatever level of queasiness or amusement they might inspire—is not actually that anyone finds the former FBI director or the special counsel attractive. In the odd parlance of the internet, this kind of language is a way to express intense emotional involvement with an issue. Half-jokingly and with some degree of self-awareness, the many people who profess their admiration are projecting their swirling anxiety and anticipation over the Russia investigation and the fate of the Trump presidency onto Mueller and Comey. Facetious admissions of crushes are only one manifestation of this emotional entanglement. Benjamin Wittes, who has been open about his friendship with Comey, has told me that his Twitter feed and email inbox have been “flooded” with expressions of support and appreciation for the former FBI director.

But even among the president’s most aggressive opponents on the left, the admiration is far from universal. As the Democratic Party and more radical lefties grapple with the new shape of politics under the Trump administration, one of the fiercest debates has focused on how to approach the Russia investigation: whether it’s an effective means by which to oppose the president and a worthwhile focus for the emotional energy of those adrift in Trump’s America or whether it’s not.

“The FBI Is Not Your Friend,” ran a headline in the far-left Jacobin magazine following Comey’s firing. “This is going to be the Democrats’ version of the Benghazi hearings,” wrote a despondent commenter on a forum for fans of the popular left-wing podcast, Chapo Trap House, the day Comey testified.

If the major story in the intellectual life of the nation over the past year has been the ideological chaos that has engulfed Americans to the right of center under Trump, the American left has its own story of chaos as well. There are a number of different American lefts. And while some have embraced the Russia investigation, others remain deeply skeptical of the investigation’s likelihood of success or even of its merit—sometimes to the point of active hostility. The story of the American left under Trump, as in the larger story, is one of bifurcation and polarization. It’s a story of a profound emerging divide over the role of patriotism and the intelligence community in the left’s political life. To put the matter simply, some on the left are actively revisiting their long-held distrust of the security organs of the American state; and some are rebelling against that rapprochement.

***

The divide within the left on the question of the Russia investigation is hard to pin down precisely, because the left, like any broad political current, is diverse. But it runs roughly along the same line as that which more generally splits the harder left—which is sharply critical of capitalism and existing institutions more broadly—from the center-left, which is more comfortable with the market and tends to advocate more incrementalist solutions to societal problems.

To be sure, the center left is itself divided on how much energy to devote to Russia. Politico reported recently that Democrats are becoming nervous that an over-focus on the Russia probe to the detriment of bread-and-butter economic issues may harm their chances in the upcoming 2018 election. Senator Chris Murphy (D-CT) has been a major voice for this view within Congress, going so far as to call the probe a “distraction” and suggesting that “regular folks” care about “jobs, wages, schools” over L’Affaire Russe.

A growing group of those on the center-left agree with Murphy: Russia is important, they argue, but shouldn’t be allowed to distract focus from more pressing issues at hand. During the recent debate over the repeal of the Affordable Care Act, reminders from prominent voices not to forget about the health care debate amidst the constant stream of news about Russia often took the tone of a parent reminding a child to eat their vegetables before turning to dessert. In a typical example, the former Obama aides of the popular Pod Save America podcast expressed concern that they’d allowed the show’s discussion of Russia to outpace its healh care coverage—even though, they admitted, the “pod” receives greater traffic when Russia is in the news.

But there are also those on the center-left who consider L’Affaire Russe to be a matter of predominant importance. They tend to be less affiliated with the institutional Democratic Party and more in the camp of concerned citizens voicing their anxieties online. They are also more likely to express love or admiration for James Comey or Robert Mueller and use language like “patriot” and “treason.” Much has been written about the phenomenon of anti-Trump misinformation spreading virally on Twitter and elsewhere, where participants tend to view the Russia investigation as a master narrative of the Trump administration subsuming all other concerns. This approach—heavy on the conspiratorial implications, light on substance—isn’t shared by all those who prioritize the Russia investigation, though it has certainly drawn the most attention.

The broad point, however, is that within the center-left, the question of the Trump-Russia scandal is a question of emphasis relative to other priorities. Its importance, not to mention the reality of a serious problem, is on its own terms largely accepted.

This is not the case further to the left, where for a variety of reasons, many commentators believe the matter warrants no energy or attention at all—and some even spend energy emphasizing how little attention and energy it warrants. The most common reason is agreement with an extreme version of Senator Murphy’s belief that the investigation is a “distraction” from policy debates. While mainstream Democratic hosts of Pod Save America took an apologetic tone in suggesting to their listeners that focusing on health care might be a better use of their time than tracking Mueller’s movements, the hosts of the Chapo Trap House podcast actively dismiss those who closely follow the latest news on Russia.

The Chapo team is happy to acknowledge that there may well be something to these ongoing investigations; they just don’t really care. “I find it amusing and am for anything that stitches up Trump and Republicans,” said Chapo host Will Menaker after Comey’s firing, “but I can’t muster anything too substantial to say about it.” The other hosts exploded with mockery of the Twitter users who expressed admiration for Comey. The former FBI director was “probably the greatest patriot of all time, of any country, and the new leader of the resistance,” host Felix Biederman declared sarcastically.

Some writers take a more actively hostile attitude. The Intercept’s Glenn Greenwald and numerous writers at The Nation have described the public focus on the investigation as a revived McCarthyism or “Kremlin-baiting,” with Americans newly suspicious of even benign connections to Russia. In this view, whether or not there is substance to the Russia investigation, the political and media reaction to the available facts has been unduly “hysterical”; Americans are primarily reacting not to the news itself, but to their prejudices against Russia. A small minority even goes so far as to deny even widely accepted, publicly available information, such as Russia’s involvement in the hacking of the Democratic National Committee or even whether the DNC was hacked at all.

The legacy of the Cold War is hard to disentangle from this position. Within the pages of The Nation, Stephen Cohen, Victor Navasky, and Patrick Lawrence have made the case that Americans’ “McCarthyite” paranoia is pushing the country closer and closer to a dangerous and unnecessary confrontation with Russia. Others, including Greenwald, activist Max Blumenthal, and Noam Chomsky have voiced similar concerns over rising tensions between Washington and the Kremlin over election interference. Their worries are strikingly similar to those voiced by American leftists advocating against a confrontational posture toward the Soviet Union. “It’s one of the few decent things Trump has been doing,” Noam Chomsky said of the alleged contacts between Trump associates and representatives of the Russian government.

As Peter Beinart has written in the Atlantic, these thinkers “loathe Trump … but they loathe hawkish foreign policy more”—and they see the Russia investigation as a tool of that familiar imperialism. To a limited extent, there is probably also an affirmative pull toward the Kremlin in particular. Paul Berman, who has written extensively on the intellectual life of the left, described this as to me as a “living sympathy” as a result of the long shadow of the Cold War and despite Vladimir Putin’s shift toward far-right government. Some of the writers in question, after all, took the extreme dovish position with respect to the Soviet Union in its day as well.

There is some justification in pointing to sloppy reporting in the American press on Russia and more widespread misunderstandings of the Russian government within the United States: Joshua Yaffa has extensively discussed the tendencies of American journalists to assume an unrealistic level of organization and strategic coherence in the Kremlin’s activities. But these critics on the left are apt to jump from instances of journalistic exaggeration—even errors—to the conclusion that there is little to the Russia story at all, despite the mounting volume of evidence that, at a minimum, the Russians actively intervened in the election and had a variety of relationships with people involved in the Trump campaign. Similarly, these leftist critics often blur the line between their skepticism of fevered speculation and the increasing pile of substantive and unrebutted reporting on the subject in order to cast doubt on even the reputable journalism on the matter.

There’s another stream of thought too, from voices who tend to be younger and more focused on left-wing domestic policy, rather than Cold War-inflected foreign policy—people whose formative political experience dates to the Iraq War, rather than anything to do with the Soviet Union. This stream tends toward isolationism.

These commentators are deeply skeptical—even hostile—to aggressive U.S. actions toward Russia in response to election interference, such as the recent sanctions legislation, because they are hostile to confrontations overseas in general. “Many (including me) assumed that [Clinton] was going to win and get us mired deeper in Syria” as a component of a proxy war against Russia, David Klion, a freelance journalist who writes about U.S.-Russia relations, wrote to me. “And so we were prepared to advocate against that, and when people who would have wanted [intervention] lead the Russia charge, some see them as warmongers.”

Instead of an affinity toward Russia or a rejection of U.S. activities abroad, this group is motivated primarily by domestic politics, particularly by a desire to shape the future direction of the Democratic Party. There is a strong sense that Hillary Clinton’s electoral defeat represented a failure of centrist liberalism and an opportunity for those further to the left—many of whom supported Bernie Sanders during the Democratic primary—to recreate the party in their image. In a fashion that sounds a lot like Trump himself, these commentators argue that Democratic politicians’ focus on the Russia investigation is a cop-out, a means by which to insist that the Kremlin, and not the moral emptiness of center-left liberalism in America, lost Clinton the election. “[F]ixating on Russia allows establishment Democrats to avoid asking any hard questions about why Hillary Clinton lost,” writer and activist Chip Gibbons argued in Jacobin. “The Russia framing helps them justify staying the course rather than finding fault with the party … [which] is fundamentally a capitalist one with deep ties to Wall Street.”

These factors have pushed both wings of the hard left—those concerned over supposed McCarthyism and for a soft line on Russia and those advocating for a redirection of the Democratic Party domestically—away from any kind of enthusiasm for the Russia investigation.

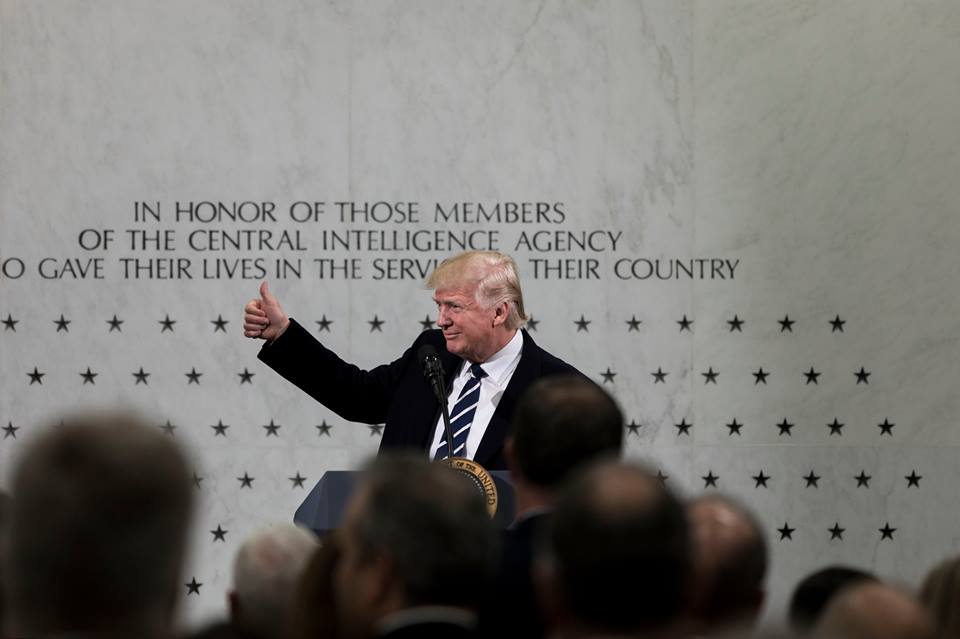

But these arguments have taken place against the backdrop of a much greater and more visible embrace of the investigation on the part of the center-left—and a concurrent embrace by many center-left commentators of actively patriotic vocabulary that is traditionally the province of the right, along with a skepticism about Russia that has not been in fashion in Democratic circles since the Scoop Jackson wing of the party bolted. As Trump has attacked and belittled the intelligence community’s assessment of Russian election interference, the center-left has embraced not only the report but also the intelligence community itself. And it has done so with the kind of sudden and intense affection that leads Vogue to run an article on Robert Mueller as “America’s new crush.”

***

Prior to the Trump presidency, left of center Americans tended to hold the intelligence community at arms’ length. Revelations of government misconduct in the Watergate and Vietnam eras still cast a long shadow—especially given that a significant portion of this misconduct was directed toward the left in the first place. The Snowden disclosures only exacerbated the distrust of those not reassured by what Jack Goldsmith and Benjamin Wittes have described as the “grand bargain” of increased intelligence oversight in response to the overreaches of Watergate and COINTELPRO. On the other side of the political spectrum, Americans on the right—though not always the libertarian right—have tended to regard the intelligence community as a crucial component of the country’s national security apparatus. Political leaders of the center-left always had a quiet peace with the national security apparatus. But the peace was a quiet one, generally speaking, one without overly demonstrative displays of affection or support.

Trump has flipped this dynamic. His sustained antagonism to what his allies call the “deep state” has generated the odd spectacle of a Republican White House and its allies engaging in partisan attacks on the intelligence community while Democratic politicians gain political points for defending it. Yes, there are exceptions: Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) has shown no sign of letting up in his critique of the government’s use of FISA Section 702, for example, though he has aggressively pursued the Russia investigation in his public appearances on the Senate Intelligence Committee. But broadly speaking, the center-left these days sounds a lot like the mainstream right of the last few decades before Trump came along: hawkish towards Russia and enthusiastic about the U.S. intelligence apparatus as one of the country’s key lines of defense. And the mainstream right sounds a lot like the center-left on the subject—which is to say very quiet.

This new posture for the center-left, to some degree anyway, has politicians speaking the language of the intelligence world: the language of active patriotism. Testifying before the House Intelligence Committee on Russian election interference a month before his firing, Comey declared: “I truly believe we are a shining city on a hill, to quote a great American. And one of the things we radiate to the world is the importance of our wonderful, often messy, but free and fair democratic system.” In a previous world, many left-of-center hearts might have been unmoved by Comey’s sincerity and deliberateness in praising the unique power of American democracy; he was, after all, quoting Reagan. But with the center-left newly admiring of Comey following his dismissal, this sort of language seems suddenly normal and attractive to left-of-center communities.

But this embrace both of the national security state and of demonstrative expressions of uncomplicated love of country is profoundly unappealing to the harder left, which has not abandoned the suspicion of the both America as a project and its intelligence services. Whether because of Cold War-inflected, foreign policy-focused anxieties or the domestic policy-focused concerns of the younger lefties, the harder left resists remains skeptical of the idea of American goodness at home or abroad—and that makes the embrace of patriotism hard.

For these analysts, and particularly among younger leftists, whose politics are steeped in ironic detachment (the Chapo podcast has been dubbed emblematic of a new “ironic left”), Comey’s case for the importance of protecting American democracy as Reagan’s “shining city on the hill” reads as naive at best and shamefully hypocritical at worst. “Hacking emails and supporting parties? This is stuff we do to [Russia], and have done to them for decades, and still continue to do,” Greenwald argued recently in an interview with Slate’s Isaac Chotiner.

“This burst of righteous indignation [in response to Russian election interference] would be easier to swallow if the United States had not itself made a chronic habit of interfering in foreign elections,” Stephen Kinzer argued in the Boston Globe, citing a variety of covert action campaigns undertaken by the intelligence community. (Kinzer had previously written that “we should drop our Cold War hostility and work with Russia” to assist the Assad regime in Syria.)

Some writers have voiced concerns that the intelligence community is engaged in an antidemocratic effort to undermine the Trump administration using what Greenwald calls “classic Cold War dirty tactics.” “Mark my words,” Max Blumenthal said recently on Fox News host Tucker Carlson’s show, “when Trump is gone … this Russia hysteria will be repurposed by the political establishment to attack the left and anyone on the left.”

If the Cold War looms over this conversation, so too does the war in Iraq. Those on the left are deeply skeptical of “Never Trump” voices on the right, many of whose most prominent members are linked to the George W. Bush administration and the push to topple Saddam Hussein. American leftists have watched with trepidation as an uneasy alliance has emerged in recent months between the center-left and those who have held firm on the Never Trump right, which many see as an irresponsible “rehabilitation” by the center-left of neoconservatives responsible for the Iraq War.

To some extent, this stems from a discomfort with hawkishness on either side of the political spectrum and a particular discomfort with hawkish language used against Russia from both left and right. But there is also a strong belief on the left that Trump is the responsibility of the Republican Party and should be treated as such: not an anomaly but nothing more or less egregious than the GOP’s natural standard-bearer. Attacking Trump on the basis of the Russia Connection is fundamentally misguided, in this argument, because it leaves the rest of the party—including Never Trumpers who have since distanced themselves from the institutional GOP—untouched. “The thing that annoys me about all of this constitutional crisis stuff is that the crisis is the Republican Party,” Menaker exclaimed on Chapo Trap House immediately following James Comey’s firing. “The crisis is right-wing governance in America.” Emmett Rensin has made this point extensively in the left-leaning new media outlet The Outline, writing, “For the masters of the American empire … [Trump’s] cardinal sin ... is only being so stupid and malicious that he might crash the whole long con into the ground.”

In the end, both the center-left and those further to the left are reacting less to the work of Robert Mueller and the House and Senate Intelligence Committees than to the set of images and concepts that have come to stand in for the investigations in the public mind. The concepts associated with the investigations in the minds of those who invest hope in them—patriotism, the bravery and integrity of the intelligence community, and the restoration of the American project—cut against the grain of the hard left’s sense of self.

***

As with so many things about our current era, the question is whether and how the dramatic changes Donald Trump has wrought will continue outside the very specific context of his presidency. We might find that this realignment of the center-left toward the intelligence community falls apart as soon as real policy stakes are on the table once again. The work of the intelligence community, after all, is far larger than L’Affaire Russe, which is one of the reasons Trump’s attacks on it are so troubling. Mainstream Democrats have not yet had to place their newfound alliance with the intelligence community in the context of the host of policy issues on which they’ve historically had anxieties about intelligence community authorities. The looming reauthorization of Section 702 in December 2017 will serve as an interesting test case here given the discomfort with which many on the center-left view large-scale surveillance.

Alternately, perhaps the center-left’s realignment will hold through the rest of the Trump administration as the Russia investigation continues and as the left and center-left dig in on their newly different approaches to opposing the president. Policy concerns may play second fiddle to “resistance” understood more broadly; in fact, that’s exactly what concerns those on the left who criticize the center-left’s new bedfellows. After the Trump presidency draws to a close, those closer to the center may drift back closer to those on the further left in terms of their distaste for the language of patriotism and the county’s hard-power agencies.

The final possibility, however, is that this is a more lasting shift with implications beyond Trump and his presidency: a sea change in how the center-left relates to the intelligence community and a deeper cleavage between the hard left and center-left on national security. This strikes me as the least likely scenario but also the most interesting. It would, of course, be one of the great ironies of Trump’s tenure if one of its lasting intellectual impacts were a rediscovery on the part of the mainstream left of the dangers posed byRussia and the need for strong and capable intelligence agencies.

But there is something troubling to this possibility as well. Several times, Lawfare’s own “handmaiden of power” Benjamin Wittes has cautioned his newfound admirers on the left that they will find plenty to dislike about him for once the sturm und drang of the Trump administration has passed. There’s solace in this idea: the notion that this, too, shall pass and we’ll return to the world we knew before, when our main disagreements were about things like the appropriate scope of surveillance authorities and the Authorization for the Use of Military Force. On the other hand, if this shift in alignment of the center-left endures and those disageements fail to reemerge, then our previous world—whatever its irrationalities and failures—will be gone, in some small way, for good. Whatever the merits of a permanent change in the center-left’s attitude toward the intelligence community, it is also discomfiting to think that Trump’s most egregious excesses might have such lasting power over the intellectual life of the nation.

-(1).jpg?sfvrsn=b91ff6a6_7)