The Media Has Overcorrected on Foreign Influence

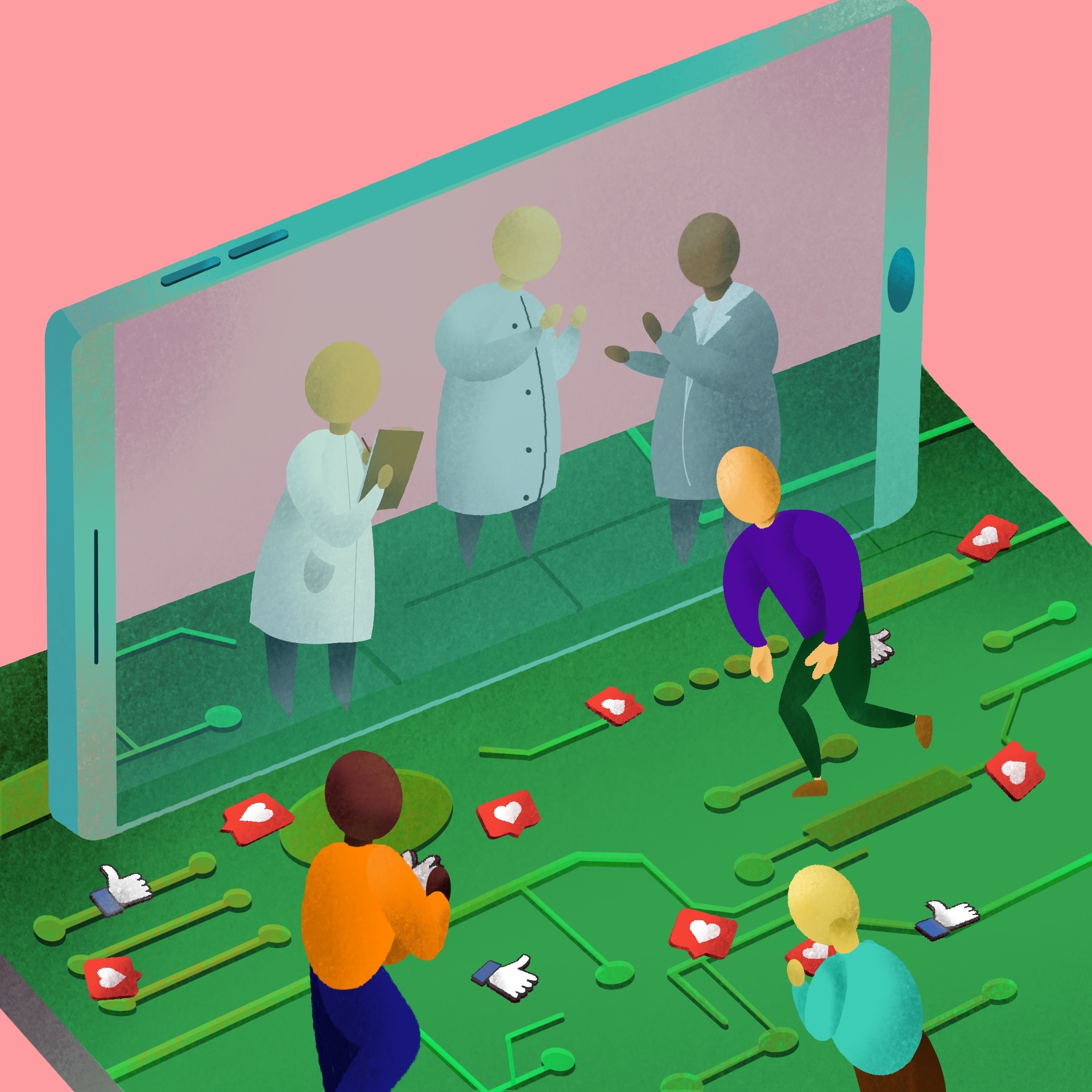

The continued focus on Russia, at the expense of domestic threats, is significant and dangerous.

In partnership with the Stanford Internet Observatory, Lawfare is publishing a series assessing the threat of foreign influence operations targeting the United States. Contributors debate whether the threat of such operations is overblown, voicing a range of views on the issue. For more information on the series, click here.

To describe the past four years as a roller coaster seems inadequate. A bungee jump into a ravine would be more appropriate. Four years ago, even as evidence of foreign meddling in the U.S. presidential election piled up, skeptical journalists remained unconvinced. But since then, many members of the press have overcorrected. Now, the challenge is trying to persuade journalists that it’s not the Russians that are the biggest problem.

It’s hard to remember when that journalistic skepticism of foreign interference morphed into a zealous belief that Russians were under every bed. But over time too many headlines included words straight off an election meddling bingo card—“bot networks,” “sock puppet accounts,” “hacking,” “the Russians.” This headline from NPR encapsulates the pattern: “How Russian Twitter Bots Pumped Out Fake News During the 2016 Election.” And once these stories arrived, they continued ad nauseam. There are lots of possible explanations for the explosion in coverage. Maybe it was the traffic. As journalists became aware of the events of 2016, so did the public. Every story raised awareness and got a whole lot of clicks. Rinse and repeat.

Around the same time, a disinformation industrial complex was established. New tools were built (Botometer, Bot Sentinel), new nonprofits founded, conference after conference organized, documentary after documentary (“After Truth,” “Operation Infektion,” “Agents of Chaos”) produced, funding opportunity after funding opportunity explored. While the focus on disinformation in general was welcomed, the continued focus on Russia, at the expense of domestic threats, was and continues to be significant and dangerous.

That’s because a number of different domestic actors warrant serious attention.

First are sources who come from institutions whose members used to be presumptively reliable. This most notably includes elected officials and other government actors. Of course, the majority of the people remain vital for providing information and context, but a small but growing number are now learning to lie and deny. Behavior that would have been unthinkable even five years ago has become normalized because of the absence of any social or reputational penalty for lying. It’s hard to describe their actions as anything other than disinformation—deliberately propagating false information with the intention of causing harm to others, whether that’s political opponents, members of the public or different communities that they are meant to represent.

Second are those who aren’t elected members of Congress but who do want to create trouble for the sake of it. They are deliberately trying to manipulate the media ecosystem, often by fooling the media into covering a false story, even trying to convince the media that it’s “the Russians”. They aim to decay trust in news organizations; their aim is to be able to say, “We told you that we can’t trust the lamestream media.” They also try to manipulate the platforms. They hijack Twitter trending topics and edit Wikipedia entries so that they show up on the front page of Google and overwhelm recommendation engines. Again, this might be another technique to fool the media into covering something bogus or devoting major attention to something wildly obscure. That oxygen and amplification provided by the mainstream media is frequently the desired ambition of these domestic actors.

Third are those who have been radicalized—often with the help of people in either of the first two categories—into believing increasingly outlandish claims, all designed to undermine trust in democractic institutions such as universities, public health authorities, the media, the government and the electoral system. Fringe positions and beliefs have exploded in communities online over the past six months. These communities emphasize radical skepticism—a refusal to accept official advice or expertise. They also mix previously disparate and separate campaigns. In Facebook Groups devoted to complaining about “Excessive Quarantine” there are also QAnon believers, anti-vaxxers and Second Amendment enthusiasts coming together. They all view themselves as fighting for the ideals of liberty and freedom, all the while being told to fear and mistrust anyone who doesn’t agree with them. It’s hard to know whether people sharing this content know that it’s misleading, and it’s tough to decide whether to classify it as disinformation or misinformation. Many of these people really do believe everything they post online, and they evangelize during conversations they have with friends and family around dinner tables. Others care less about the substance and more about feeling connected to a community, about feeling heard. Either way, these individuals become vectors for misinformation—far more destabilizing than a gaggle of “Russian troll bot accounts.”

The divisions within American society, and many others, are now so deeply ingrained that there’s no need for foreign influence in order to amplify and inflame. From the cellphone-captured footage of Americans screaming in supermarkets about masks, to family members having to disown loved ones because of outlandish beliefs, to a neutered Centers for Disease Control and Prevention whose downfall was fueled by and consequently fueled misinformation, to university lecturers terrified of being filmed by students looking for evidence of liberal bias, to a weakened news media falling almost on a daily basis in the trust ratings, the evidence of our divided society is all around us.

The fissure between left and right, between the religious and atheists, between the coastal elites and those who live in the “flyover states” emerged decades ago, and the canyon continues to widen today at an ever-faster rate. Foreign actors can do whatever they want to speed things along, but there’s little they can do that America isn’t already doing to itself. Ultimately, historians of Russian disinformation campaigns taught us that this was always the objective, but the warning was not heeded. We need to recognize that a myopic focus on “Russian meddling” is preventing a much deeper analysis of what is happening right here at home.