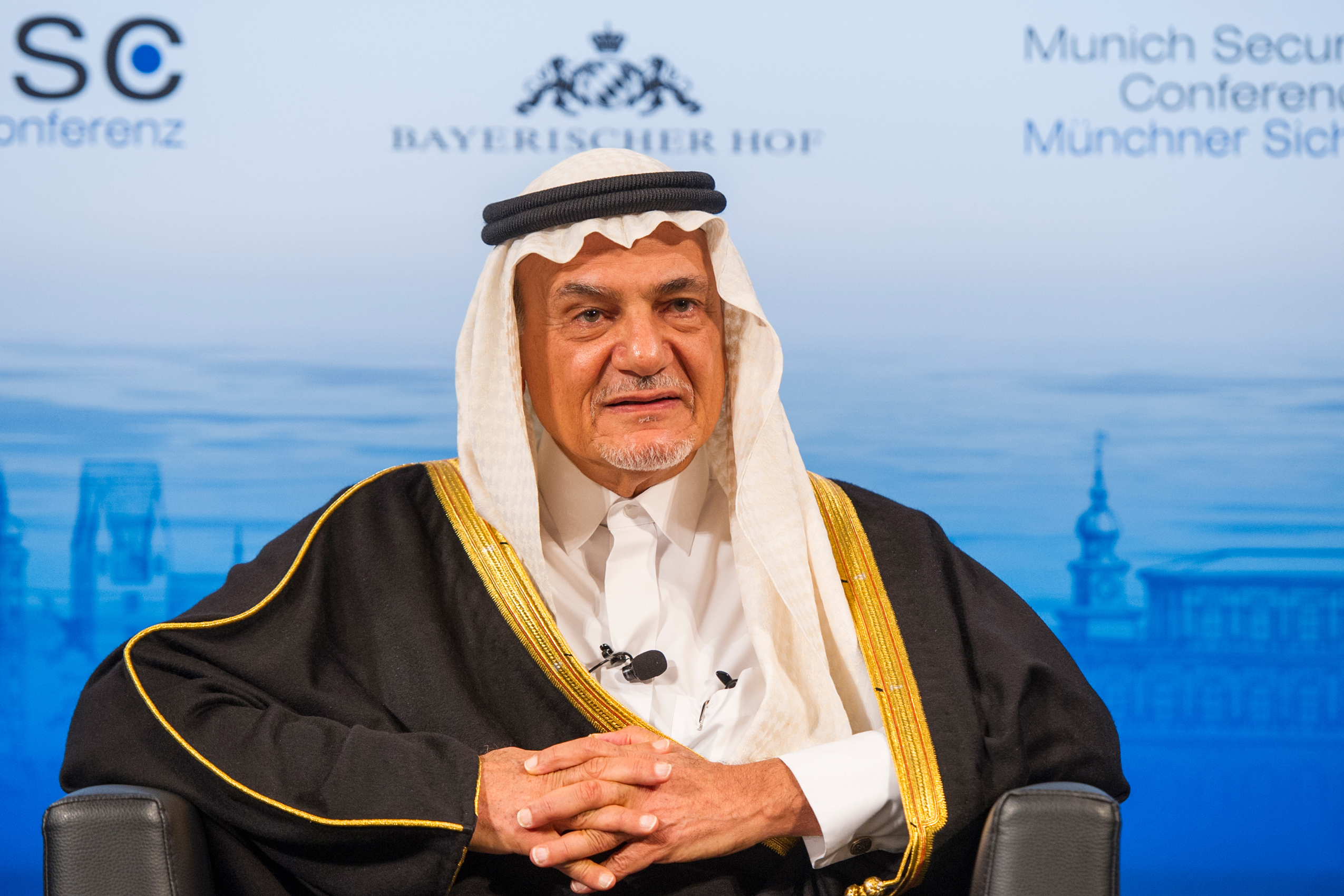

A Memoir From the Head of Saudi Intelligence

A review of Turki AlFaisal Al Saud, “The Afghanistan File” (Arabian Publishing, 2021).

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

A review of Turki AlFaisal Al Saud, “The Afghanistan File” (Arabian Publishing, 2021).

***

Prince Turki AlFaisal Al Saud has produced an insightful and engaging memoir of his 24 years as head of the Saudi General Intelligence Directorate (GID). His focus is on Afghanistan, where he was a central figure. He provides much new information on the Saudi role between the Soviet invasion in 1979 and the start of the American war in 2001.

Half of the book is devoted to the war against the Soviets. After the invasion, President Carter quickly organized the coalition to support the Afghan mujaheddin fighting against the Russians and their Afghan communist allies. Saudi Arabia and the United States would fund the Pakistani intelligence service (ISI), which would provide sanctuary, weapons, advice and other assistance to the rebels. The British also helped, sending commandos into Afghanistan to help the mujaheddin (no Americans crossed the border). The CIA bought arms for the mujaheddin, chiefly from China and Egypt.

Turki had just become GID chief two years earlier. He got the job because his predecessor had failed to predict and prevent Egyptian President Anwar Sadat from making his historic trip to Jerusalem in November 1977, a trip the Saudis regarded as gravely weakening the Arab coalition against Israel and its occupation of Arab territory, including East Jerusalem.

The prince provides facts and figures for the extent of the Saudis’ aid to the war effort. Between 1977 and 1991, the Saudi GID, working through the ISI, spent $2.71 billion for the mujaheddin. (The CIA matched the Saudi contribution.) Saudi private sources—including members of the royal family, clerics and average citizens—provided $4.5 billion more in aid to the mujaheddin or to help the millions of Afghan refugees in Pakistan. The private-sector money was crucial to the war, especially in the years before Ronald Reagan increased annual aid to $500 million in 1985. And at the center of the private fundraising was current Saudi King Salman, then the governor of Riyadh.

Turki reports that about 15,000 Saudi citizens went to Pakistan during the war on their own initiative to help the war and relief efforts. Only a handful actually fought in the war, and none died in combat. Of course the most famous was Osama bin Laden, who according to Turki (and consistent with other accounts) greatly exaggerated his role and that of the Arab fighters.

Turki recounts that, in late 1988 and at the request of the Soviets, he convened in Taif, Saudi Arabia, a secret meeting of the Soviets, the mujaheddin and Pakistan. The Russians secured a promise from the mujaheddin that their withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan would not be a bloody retreat but instead an orderly, peaceful withdrawal. And a trouble-free retreat is indeed what happened. Turki’s account of the meeting is the most in-depth account that has ever been made public.

The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait provides a break from the Afghan story and introduces the second half of the book. By coincidence, Turki was in Washington on Aug. 2, 1990, the date of the invasion, and was the first Saudi official to meet with the Americans to discuss a response. National security adviser Brent Scowcroft promised Turki full and immediate American support and proposed sending American troops to defend the kingdom, a campaign that became Operation Desert Shield.

Returning to Afghanistan, Turki describes how, after the Soviet withdrawal, the United States rapidly lost interest in Afghanistan, leaving the ISI and GID to cope with the chaos that followed, including the endless infighting in the mujaheddin movement and the rise of the Taliban. Turki categorically denies that the Saudis gave any money to the Taliban, who he claims were Pakistan’s ally.

He also recounts his two meetings in 1998 with Mullah Omar, the Taliban’s reclusive leader, intended to get him to turn over bin Laden to Saudi Arabia. In between the two meetings, al-Qaeda had attacked the American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. Washington responded with a cruise missile strike on a camp in Afghanistan. According to what the Taliban told the Saudis, bin Laden had left the camp just 10 minutes before the missiles landed. Omar refused Turki’s request to hand over the terrorist leader, and the second meeting ended in a shouting match, with Turki angrily walking out.

Turki also sheds light on the founding of al-Qaeda, reporting that bin Laden left the kingdom in 1992 for the Sudan with as much as $50 million of his wealthy family’s money to set up al-Qaeda and that Bin Laden was very much under the influence of his deputy, the Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahri.

After leaving the GID in 2001, Turki went on to be the Saudi ambassador to the United Kingdom and then to the United States. I recall meeting him in London in 2002 (we had known each other for years) and his strong but private opposition to the idea of invading Iraq, which he predicted would be an expensive quagmire. British Prime Minister Tony Blair and President George W. Bush ignored his prescient warning.

Saudi princes rarely write memoirs. This is a very useful one. The timing of its publication just after the disastrous American withdrawal from Kabul and the return of Taliban rule makes this a particularly important book. Afghanistan is far away from America, but two of the most consequential events in recent U.S. history happened there. First was the defeat of the Soviet army by the mujaheddin in the 1980s, followed shortly by the collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the liberation of Eastern Europe. Second was the rise of al-Qaeda and the attack of Sept. 11, 2001. This book is essential reading for those wishing to understand both events.