The Mexican-American War and Constitutional War Powers

The outcome of the war—and the means necessary to achieve it—led to the war’s most noteworthy constitutional precedents.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On this day in 1848, the United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending a two-year war. The treaty set the southern Texas border at the Rio Grande and ceded Mexico’s northern provinces (which now include California and large parts of New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah and Colorado) to the United States in return for $15 million. In July of that year, the Senate approved the treaty’s ratification.

In discussions of constitutional war powers, it’s the start of the Mexican-American War that gets most of the attention. Congress’s move in 1845 to annex and grant statehood to Texas probably set the countries on a path toward eventual war. Nevertheless, the main constitutional controversy in most accounts of the war is that President James Polk pretextually manufactured a border crisis to pull Congress into declaring war over American blood spilled in the disputed region between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande (which the United States and Mexico, respectively, regarded as the proper national boundary). Polk had sent Army units into the contested territory, essentially baiting Mexican forces into firing the first shot. Polk had also already drafted a war declaration for Congress before word of the skirmish reached Washington in May 1846. When Polk told Congress that Mexico had killed American troops, his allies rushed the declaration through Congress.

The start of the Mexican-American War is only one of many important constitutional dimensions of the conflict, though, and I don’t think it’s the most interesting. I’m writing about this conflict on the anniversary of its end because its outcome—and the means necessary to achieve it—led to the war’s most noteworthy constitutional precedents.

True, this is probably the clearest early example of a president unilaterally starting a war (an especially hot issue now with regard to Iran). Although Congress declared war, the House of Representatives in 1848 passed a resolution pronouncing the war “unnecessarily and unconstitutionally begun” because Polk had deliberately induced it. But American history is replete with examples of presidents wielding their military and diplomatic powers to set the United States on a path toward conflict and using their control of information to press Congress to authorize it. For example, Thomas Jefferson went to Congress for authorization to fight the Barbary States after first sending to the Mediterranean a squadron, which was predictably attacked. In 1818, Congress mustered no formal response when the Monroe administration defended General Andrew Jackson’s “defensive” campaign across Spanish Florida.

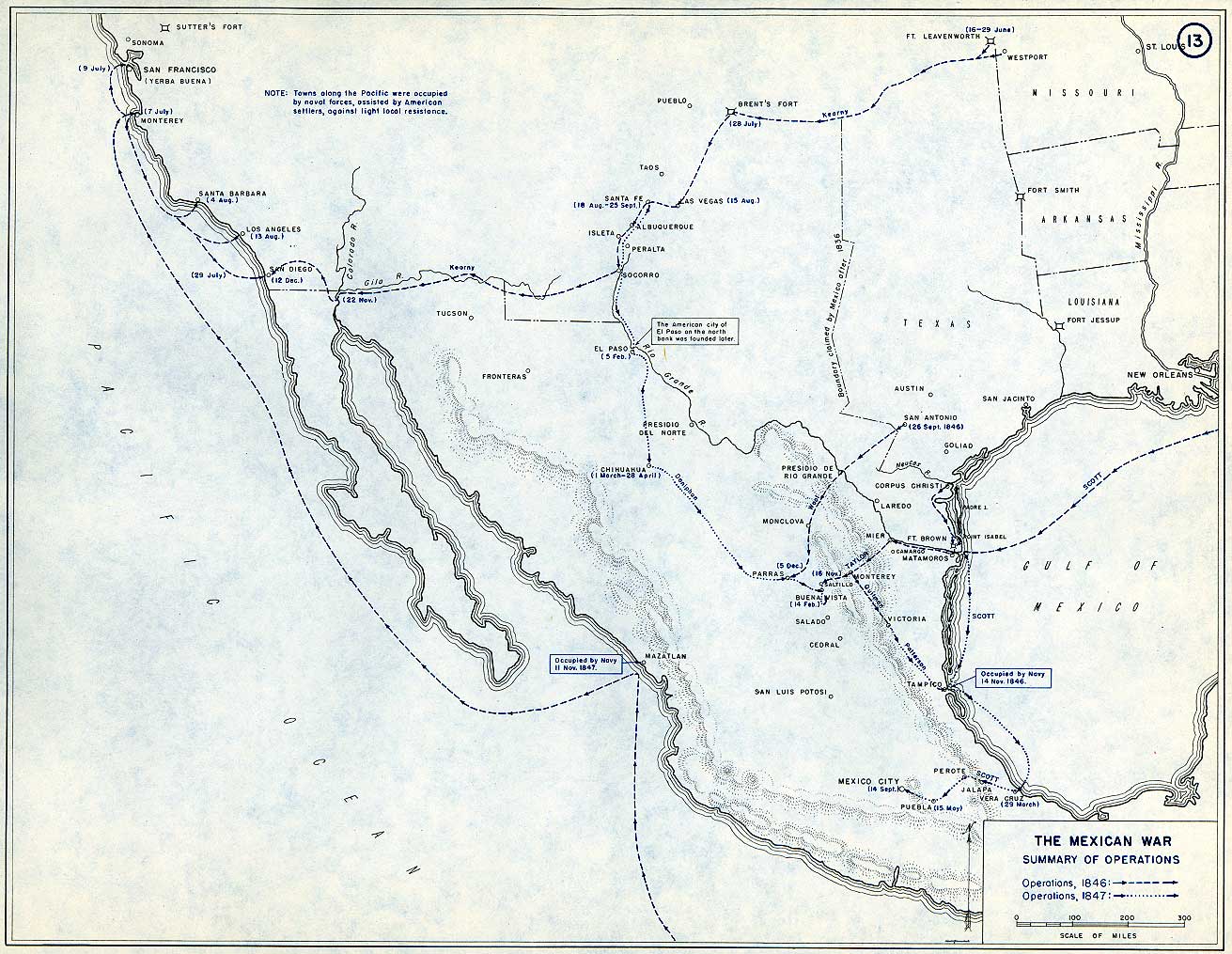

Focusing on the end of the conflict helps bring into sharper focus many other important constitutional dimensions. This was the republic’s first major war of conquest. Polk’s strategy was to seize quickly Mexico’s northern provinces and areas to the west and south of Texas, in combination with blockading Mexico’s eastern ports, to compel Mexico to give up its northern provinces. If Polk had only sought to grab militarily the disputed Texas border region, even his aggressive moves that provoked war would surely have been viewed in much less negative constitutional light. Polk’s ambitious territorial war aims and strategy for achieving them, however, raised four other big constitutional issues that are at least as significant as how the war began.

Who Controls War Objectives and Termination?

One lesson—still relevant today—is that Congress’s control over war declaration does not ensure careful, interbranch deliberation about war ends. One remarkable aspect of Congress’s debate over Polk’s proposed war declaration is how little attention is devoted to desired goals. Polk had long coveted California, and the debates were infused with the expansionist spirit of Manifest Destiny, so many members of Congress who voted for war surely approved implicitly of Polk’s ambitious objectives. But, reading the war resolution itself, one might think that the desired end-state was confined to resolution of the Texas border and restoration of American honor. Even some members of Polk’s own cabinet seemed caught off guard by his unilateral decision to dramatically expand war aims to include the entire northern provinces.

Although Congress failed to involve itself much in setting war aims at the outset, it began to assert itself as the war dragged on. Wars at that time customarily ended through peace treaties, which meant that the president ultimately needed two-thirds of the Senate to approve a negotiated settlement. Some opposition senators sought to use this leverage to constrain the president’s war objectives, which they believed should not include new territory. That issue of territorial expansion was inextricably bound up in the divisive issue of slavery, since the addition of new states would likely upset a precarious balance between slave and nonslave ones.

Polk and Congress had assumed it would be a quick war, but after a year of fighting, and therefore needing much more funding from Congress, Polk found himself squeezed between political opposition to annexing any new territory beyond Texas and political opposition to settling for anything short of “all Mexico.” In the end, Polk’s military success in occupying Mexico’s northern provinces and taking Mexico’s capital helped beat back efforts by Daniel Webster and others to forego major territorial acquisition, but congressional pressure to bring an end to the war compelled Polk to hastily accept treaty terms that he considered imperfect. Polk may not have worried much about Congress in starting the war, but he eventually needed to heed Congress on war aims in waging and ending it.

What Is a Commander in Chief?

As a matter of constitutional war powers, equally notable to the way the United States went to war were ways Polk filled out through his wartime actions a much more capacious role as commander in chief than any previous president. Polk personally exercised wartime military command, diplomacy, legislative advocacy and administration like none of his predecessors.

Polk’s vigorous White House micromanagement was driven partly by his desire to coordinate military pressure with diplomatic efforts in wresting from Mexico its northern territory: Because for Polk this war was a violent negotiation, he wanted personally to control the pressure on the Mexican leadership. After securing legislation and financing to support the war, and overseeing speedy military recruiting efforts, he stayed in as close contact with field commanders as was possible at that time (telegraphs were just coming online, so this mostly meant by combinations of railroad, steamboat and horseback). He even involved himself in minute details of the planning and execution of military operations, despite his lack of much military experience compared to other presidents of the era. Some of Polk’s tight and direct war management was for purely political reasons as well, and Polk more than any other president before or after managed the wartime military with partisanship and patronage in mind.

Despite Polk’s unprecedented efforts to control the war from the White House, as the war went on, top military commanders and diplomats outrightly disobeyed him. In their march through Mexico, for example, American generals agreed to temporary cease-fires when Polk wanted them to press their advantage. His commanders viewed the moves as military decisions while Polk viewed them in terms of coercive bargaining.

In the most ironic twist, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was negotiated and signed by an insubordinate envoy—the chief State Department clerk, Nicholas Trist—whom the president had ordered recalled. Trist ignored the recall order, negotiated treaty terms with the Mexican leadership and presented the furious Polk with a fait accompli. Politically, Polk had little choice at that point but to take the text to the Senate for approval. He achieved almost everything that he wanted for a relatively cheap financial price, but this most consequential American treaty of conquest was not truly his.

This was a war in which the executive branch was in some ways more unitary than ever but in other ways, by the end of the war, more untethered.

Who Wages War?

The Mexican-American War was waged mostly by federal Army “volunteers.” Although this may not seem like a constitutional issue, it reflected debates about military power that were baked into the Constitution and the interaction of Article I’s Army and Militia clauses.

Since the Founding, American military policy (such as it was) reflected competition between two main ideas: that effective defense and warfare required regular, standing national military forces and that those purposes could be achieved—with less threat to liberty—by local, part-time citizen-soldiers. The Constitution gives Congress the power the create the former while expressly preserving the latter in the form of state militias. In its first major war, the War of 1812, the United States tried to take on the world’s greatest military power by relying on state militia forces for the bulk of its manpower. As predicted by those favoring a standing, regular army, state militia forces mostly performed terribly.

State militias in the War of 1812 performed especially badly in ways that would render state militias unsuited for Polk’s war ambitions: Besides being poorly trained, militia forces were generally limited statutorily to three months’ service at a time (too short for expeditionary warfare into Mexico, even after Congress extended the limit to six months), selection of most of their officers was constitutionally guaranteed to states (undermining Polk’s desire for control), and their federal responsibilities were constitutionally limited to “execut[ing] the laws of the Union, suppress[ing] insurrections, and repel[ling] invasions” (unworkable for offensive campaigns in Mexico). At the same time, Polk and many in Congress opposed large standing armies. The year prior to the war, Polk called them “contrary to the genius of our free institutions” and “dangerous to public liberty.”

Polk and Congress solved this dilemma by filling Army ranks with volunteers, who fought alongside a core of regular officers and who agreed to serve for one year or the duration of the war. This category lay somewhere between federal regulars and state militias; it avoided the unsuitable legal and practical restrictions on militia forces, though like other mythologized citizen-soldiers they suffered from poor discipline. This category also dated back to the early years of the republic, when for many years efforts by Congress to create volunteer forces faced constitutional criticism from advocates of both a federal army and state militias.

Volunteers’ ill-preparation for complex military expeditions, and friction and mutual suspicion between them and federal regulars, undoubtedly undermined combat effectiveness, but Polk and Congress’s reliance on them for the majority of forces reflected a Jacksonian-Democratic approach to war: resistance to large, national-government establishments and (white) western egalitarianism over eastern elitism. The Mexican-American War most clearly established volunteers in constitutional practice, and the federal government later relied on them heavily in the Civil War and Spanish-American War, after which the institutional pendulum swung sharply and permanently—though not completely—toward the regular, national military.

What Are the President’s Constitutional Occupation Powers?

As U.S. forces advanced through Mexican territory, they needed to provide for governance of territory they controlled—especially since Polk’s strategy relied on staving off anti-U.S. insurgencies in those zones. In the case of General Taylor’s offensive south of Texas, this involved occupied Mexican territory that Polk did not intend for the United States to keep, and the War Department gave Taylor specific guidance for militarily administering it. By contrast, Polk intended to seize and keep New Mexico and California. In sending brevetted Brig. Gen. Stephen Kearny on a westward offensive to take those northern provinces, the War Department provided only the barest, most general guidance about governing.

Exercising that discretion upon entering New Mexico, Kearny stunningly proclaimed not only that it was now U.S. territory but that its inhabitants who were loyal to the United States would be treated as citizens (those who were disloyal could be tried and hanged). He went on to issue new legal codes and to appoint civilian officials, including the governor and supreme court justices. Kearny and other commanders were a bit more restrained in establishing a military occupational government in California.

In his December 1846 annual message to Congress, Polk explained that, by virtue of the international laws of war, American commanders had established temporary governments in New Mexico and California, pending the war’s outcome and peace treaty. The territorial and citizenship proclamations by Kearny with respect to New Mexico certainly sounded permanent, though, and the Constitution clearly grants Congress in Article IV the power to enact laws for U.S. territories. Congress demanded clearer explanations from the executive branch, and some House Whigs criticized Polk for exercising unconstitutional, dictatorial powers. Answering Congress, Polk distanced himself from some of Kearny’s purportedly permanent actions as unauthorized, but he defended generally the establishment of temporary military government by virtue of the rights of war under the law of nations.

The constitutional debate over Polk’s commander-in-chief authority to govern occupied territories was eventually superseded, after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, by Congress’s subsequent legislation for newly acquired territories. The Supreme Court also validated a few years after the treaty that the president, as constitutional commander-in-chief, could “authorize[] the military and naval commander of our forces in California to exercise the belligerent rights of a conqueror, and to form a civil government for the conquered country.” In practice, the New Mexico and California actions stand out as dramatic examples of how presidents can assert expansive commander-in-chief powers by pegging them to international law.

* * *

Following ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in his 1848 annual address to Congress, Polk extolled the virtues of the American constitutional system for waging war: “The war with Mexico has thus fully developed the capacity of republican governments to prosecute successfully a just and necessary foreign war with all the vigor usually attributed to more arbitrary forms of government.” While understandable as political rhetoric, this was an overstatement. The United States had defeated not a major power but one that had suffered since its independence from decades of instability. That said, Polk was successful in his war in part because he was able to adapt the constitutional system to match his offensive strategy.

An irony of Polk’s claims of proving the American constitutional system’s wisdom and virtue is that the war was also part of the system’s undoing. As many critics had forewarned, over the next decade the war’s territorial spoils upset the precarious balance between free and slave states and thus contributed to the Civil War.