The Military Justice Improvement and Increasing Prevention Act: Are the Solutions Commensurate with the Problem?

The bill in its current form reshapes military justice far beyond the context of sexual assault. Congress should take care to fashion a solution commensurate with the problem at hand, and not go too far.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The Military Justice Improvement and Increasing Prevention Act of 2021 is legislation pending in Congress to reshape the manner in which the U.S. military prosecutes sexual assault within its ranks. This is reform that is much needed and long overdue. Notably, however, the bill in its current form reshapes military justice far beyond the context of sexual assault. Congress should take care to fashion a solution commensurate with the problem at hand, and not go too far.

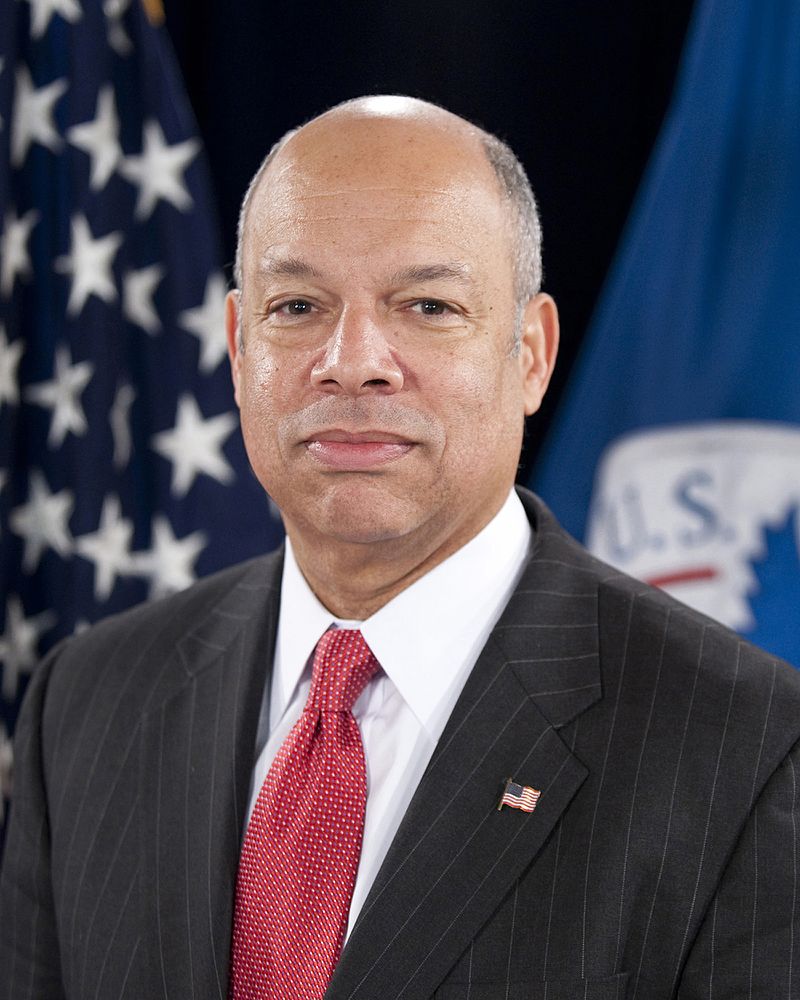

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), the principal sponsor of the bill, S. 1520, deserves credit for her heroic and persistent campaign over the years to highlight the problem of sexual assault in the military. Few others in Congress today could have assembled such a broad bipartisan coalition of 64 co-sponsors behind such an important, substantive piece of legislation, while moving (or, to put it more appropriately, dragging) the top brass at the Pentagon to the same place. From my experience 10 years ago preparing the military for the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, I know how resistant to change that community can be.

I support Senator Gillibrand’s effort to move charging decisions for sex offenses in the military to an independent, trained group of military lawyers. I said as much publicly in 2013. Likewise, almost all retired general and flag officers I speak with today agree that the male-dominated chain of command has failed the victims of sexual assault in the military. They accept the need for change.

But, in its current form, the changes contemplated by S. 1520 are not limited to sex-related offenses. The bill would create an independent body of lawyers, outside the chain of command, to make charging decisions for a broad range of offenses punishable by more than a year’s confinement. These include murder, manslaughter, child endangerment, larceny, robbery, fraudulent use of a credit card, kidnapping, arson, housebreaking, extortion, bribery, perjury, subornation of perjury and obstruction of justice. (Notably, other offenses such as receipt of stolen property, forgery and conduct unbecoming an officer are excluded from the bill’s reach, but the logic for the distinction is unclear.) In all, if enacted, the legislation would constitute the largest change to military justice since the enactment of the Uniform Code of Military Justice in 1950.

Why are offenses ranging from murder, arson to perjury included in the bill’s reach? What is the justification for so large an overhaul? Where is the congressional finding that, when it comes to the broader range of offenses, the chain of command in the U.S. military has failed in its duty to carry out military justice?

Supporters of the bill argue that, once Congress goes down the road of creating an independent body to make charging decisions for sex crimes, it cannot stop; that to limit the creation of an independent body for sex crimes would also create the stigma of “pink courts” that appear to exist for the benefit of women. In my view, the exception is warranted, perceptions can be addressed, and the exception should not swallow the rule. In both civilian and military life, the reality is the sex offenses are different, in the manner in which they are reported, investigated, and prosecuted. It should also be noted that victims of sexual assault are both men and women.

Here are several other considerations:

First, as written the bill appears to require a whole new bureaucracy to implement and execute the changes contemplated. No one should be under the illusion that the broad mission contemplated by the bill can be carried by a small band of elite JAGs in a suite someplace in northern Virginia. The bill would require that an independent group of lawyers make charging decisions for a vast range of offenses—from murder to perjury—across the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps and Coast Guard. This is no small undertaking. Realistically, it would mean standing up a new, centralized Department of Justice within the Department of Defense and the Coast Guard. Recent examples of similar undertakings by DoD do not inspire confidence: the military commissions at Guantanamo Bay created over 15 years ago, intended for a much smaller and discrete body of criminal defendants, has been the subject of numerous embarrassing legal and logistical setbacks, and the 9/11 defendants are still awaiting trial.

Second, the bill contemplates that a group of lawyers make all the charging decisions. Lawyers (and I am one) do not have a monopoly on wisdom. In the current system commanders make charging decisions, advised at all stages by lawyers. A charging decision involves two considerations: what charge fits the crime, and whether the charge is supported by the available evidence. Only the latter is a legal analysis; the former is not. The former is a matter of justice and fairness given the need to maintain good order and discipline in a unit. A retired Air Force JAG I admire much told me the following story: years ago an airman in his unit was involved in a bad traffic accident that led to the death of another airman. The JAG recommended to his base commander that the airman be charged with negligent homicide. The commander had another idea: promptly remove the airman from the Air Force by administrative action, and display the mangled, wrecked vehicle at the entrance to the base with a sign: “this is what happens when we fail to take care of another airman.” Car accidents in the command declined sharply after that.

Third, and most important, the bill in its current form would, for all sorts of misconduct, strip commanders of an essential tool in the tool box for maintaining good order and discipline in a unit. I know Congress has heard this argument, in these words, over and over again. But, consider what that means in practical, everyday terms.

A military commander must have legal authority over those in a unit. In the military, a commander can order a subordinate to take an action that may result in his or her own death. With the responsibility to prepare and send troops into battle must come the authority. The two must be inseparable. To strip a commander of the authority to make a disciplinary decision undermines the very ability to command. This should not be done lightly.

A retired four-star Marine reminded me that units vary in size, shape, mission and maturity, and as part of establishing control, he would routinely declare to his subordinates: “Here are the three things I will not tolerate in this unit.” But, if a lawyer of lesser rank and without command responsibility can overrule him and say, “well, I just didn’t see it that way,” this creates an intolerable situation, as it compromises the commander in the eyes of the troops. In their own writing on the subject, three military justice experts, Tim MacDonnell, Chris Jenks, and Geoffrey Corn, put it this way:

The strongest argument in favor of command prosecutorial discretion is that commanders are better informed and in touch with the needs of military society. This is particularly relevant when the unique needs of specific command are taken into consideration. For example, the commander of a training unit may choose to punish fraternization more severely than the commander of an infantry unit recently returned from a combat deployment. The training unit commander may make such a determination because the unique power dynamics present in a training command demands a more severe punishment than a recently redeployed combat unit. Similarly, the commander of a recently returned combat unit may make their determination based on a host of factors related to the unit’s combat deployment. The prosecutorial decision is best crafted to the needs of military society and the particular community of that society. Commanders, more than lawyers, are necessarily more aware of these various needs and competing interests.

This comports with my own experience as the senior legal and ethics official of the Department of Defense. During overseas deployments, I have seen one offense inflicted on a member of the local population threaten to undermine the entire mission in that country. In cases of detainee abuse, it is imperative that the disciplinary action by a commander send a swift and stern message to the offender and all others in the unit. More recently, in 2020, when someone at the Air Force Academy scrawled racial slurs outside the dorm rooms of five black students, it was the Superintendent, not his JAG, who delivered the forceful message “you need to get out.” In these types of instances, commanders, not an independent body of lawyers, must have the full authority to meet the moment.

No system of justice in this country, civilian or military, is perfect. They are all far from perfect, prone to basic human shortcomings. In considering S. 1520, Congress should be careful to legislate solutions limited to the problem, and remember that many institutions are broken because someone tried to fix them.