Mind the Gap: America Needs an Office of Technology Net Assessment

After costly misses on semiconductors and 5G, the United States needs to level up its analysis of long-term technology trends to better anticipate threats and secure its leadership.

Just over 50 years ago, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger stood up an independent body within the Pentagon called the Office of Net Assessment. It was 1973, and the Cold War had entered a period of detente. The previous year, President Nixon had made a historic visit to Moscow, and the two superpowers signed the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) I treaty to reduce their strategic nuclear arsenals. Amid the shifting geopolitical landscape, the ONA was empowered to step back, look ahead, and soberly assess the U.S. military’s “net” strengths vis-a-vis its competitors. A half-century after its founding, the ONA has its admirers and its detractors, but few would dispute the value of creating space within government for long-term, strategic analysis.

Today, there is a grave and growing gap in Washington’s long-term analysis: technology competition. Although the ONA has done laudable analyses of key technology trends, its focus on how those trends specifically affect the U.S. military misses the ever-expanding role technology plays in national and economic security. And within the ONA, technology competes with many other analytic priorities, even as technology leadership becomes more central to national power and the U.S.-China strategic competition in particular.

The analytic gap within the U.S. government for long-term technology trends is not a matter of speculation. It is painfully clear from three recent examples: semiconductors, 5G networks, and biotechnology.

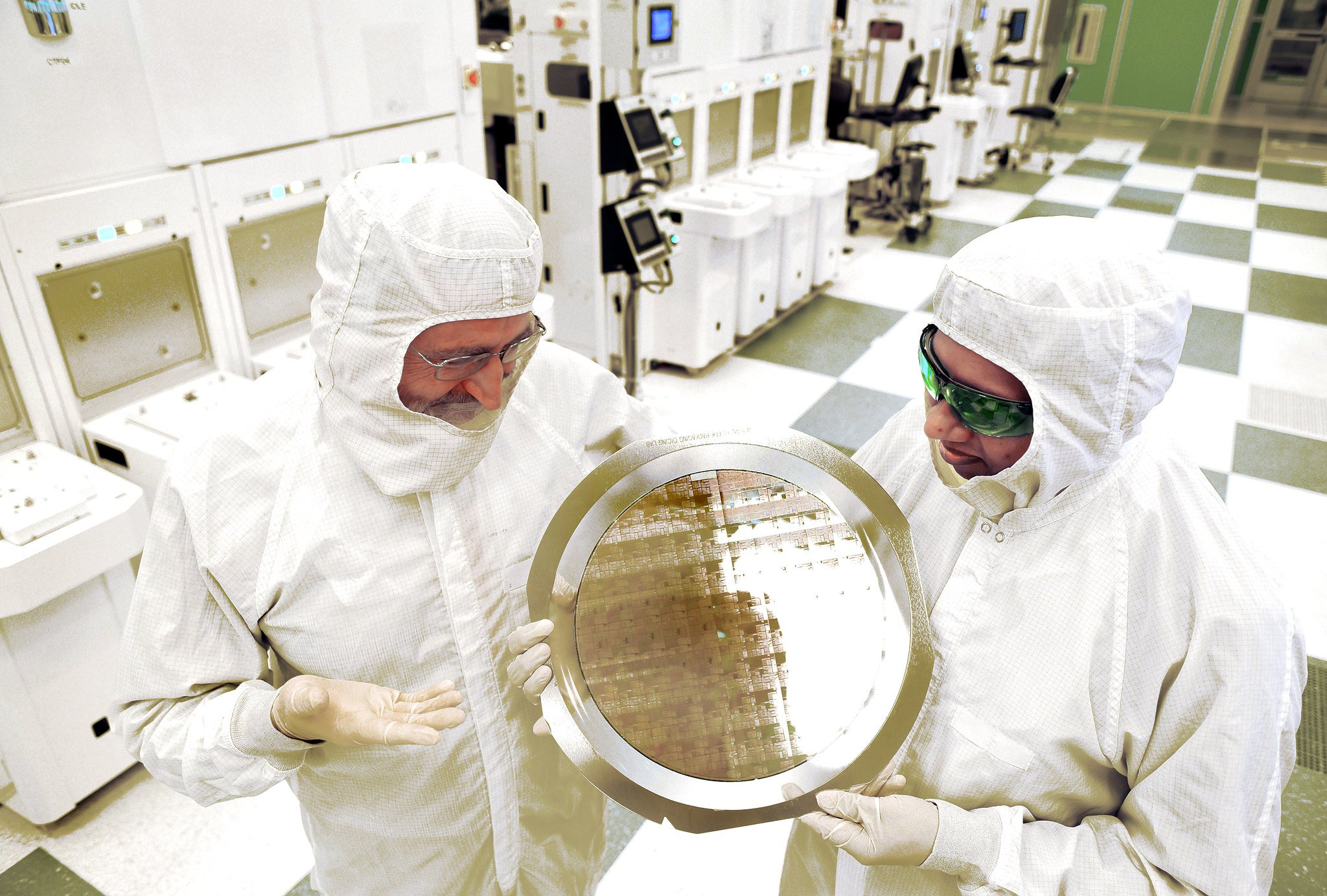

Although semiconductors have recently vaulted to the top of Washington’s agenda, they languished on the margins for decades. Over the past 30 years, Washington failed to anticipate the danger of hemorrhaging America’s chip manufacturing abroad, even as they assumed an indispensable role in the modern economy and military. Since 1990, the U.S. share of global chip manufacturing collapsed from 37 percent to 12 percent. At the same time, global chip supply chains grew dangerously concentrated, with the Taiwanese firm TSMC fabricating 90 percent of the world’s most advanced chips, while a single Dutch company, ASML, became the the only company on Earth to make the extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV) machines required to fabricate them. As this unfolded, few in Washington rang the alarm until America was already critically dependent. Once Washington recognized the danger, it rushed to throw $53 billion in subsidies to shore up domestic semiconductor manufacturing and research in the CHIPS and Science Act, which President Biden signed into law in 2022. Success is far from assured.

A similar story played out with 5G telecommunications networks. For years, Chinese firms Huawei and ZTE lapped Western carriers in deploying 5G across the globe in countries like Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia, and South Africa. This not only ceded global market share to China, whose firms are now foundational to the telecommunications architecture across much of the Global South; it also ceded leadership to Beijing in writing international 5G standards, creating data security risks for U.S. government and commercial activity. As with chips, Washington scrambled to improvise out of a crisis it had failed to anticipate. And if not for an all-out diplomatic push from Washington, Huawei and ZTE might have succeeded at deploying networks in key U.S. allies like the United Kingdom and Australia, gravely compromising data security within the Five Eyes alliance. Last year, Washington mustered $1.5 billion to support Open-RAN—a decentralized, virtualized approach to 5G deployment—as an alternative to Huawei and ZTE. Again, only time will tell if the U.S. can catch up. And 6G looms on the horizon.

Also lingering over the horizon is the biorevolution—a future in which scientists can design, manipulate, and even create life with greater power and precision. Propelled by breakthroughs in areas like synthetic biology and gene editing, the biorevolution could transform everything from agriculture to manufacturing to medicine, with up to $4 trillion in annual economic impact over the next decade. Although the White House issued an executive order on biotechnology in September 2022, which set priorities and directed agency coordination around the technology, government funding and policy remain woefully inadequate to secure America’s biotech leadership. China has made no such mistake; Beijing has set out to dominate the global biotech sector with an aggressive strategy of amassing biodata and, by some estimates, investing up to $100 billion in life sciences.

All three examples point to an obvious question—how has Washington missed such important, and seemingly obvious, technology trends? And if the ONA lacks the mandate and bandwidth to study these trends beyond their relevance to the U.S. military, whose job is it?

As it turns out, the responsibility lies in part with many agencies and fully with none. The Office of Technology Assessment once provided Congress with technical expertise and advice, but House Republicans defunded it in 1995. Today, the intelligence community surveys the technology landscape abroad in its Annual Threat Assessment, but it does not analyze domestic trends. The Department of Commerce, by contrast, focuses mostly inward but does not have the culture or capacity for long-term, relative technology assessments. Similarly, White House staff at the National Security Council and the Office of Science and Technology Policy lack the bandwidth, resources, and political independence these assessments require. Ad hoc advisory boards and congressionally mandated commissions, like the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, have occasionally filled this gap, but they are reactive, subject to policymakers’ interest in a particular technology, and therefore limited in anticipating emerging challenges. And again, the ONA looks at technology through the lens of the U.S. military—alongside a host of competing priorities.

If you want a job done in government, you have to assign someone to do it. To that end, a bipartisan group of senators have proposed an Office of Technology Net Assessment. This new office would fill a critical gap in U.S. technology policy by having the resources, independence, and mandate to look ahead and identify which technologies will matter most to U.S. national security and the economy, and assess where the nation stands relative to competitors. For example, the office could conduct in-depth analyses of America’s relative position on biotechnology by fusing analysis of the domestic bio-innovation and investment landscape, the domestic workforce of biologists, geneticists, and engineers, existing research capacity across universities, labs, and firms, and potential supply chain vulnerabilities. The Office of Technology Net Assessment could then fuse this domestic analysis with classified information about biotechnology trends abroad to provide policymakers an integrated picture of where the United States stands relative to competitors like China.

Policymakers have begun to recognize the need for this type of long-term technology analysis. Last year, the Senate Intelligence Committee unanimously approved a bill creating the Office of Technology Net Assessment as part of the Intelligence Authorization Act. Although Congress has yet to pass the bill, the White House could use its executive authority to stand up the office immediately.

Of course, no new office in Washington can guarantee America’s technology leadership. Government experts, like any other, often make the wrong forecasts, or miss tectonic shifts entirely. But that is no reason to continue navigating the digital age aimlessly, improvising from behind as we have on semiconductors and 5G at great cost, and with no assurance of success.

No one can perfectly predict which technologies will transform the 21st century, and how, but the United States won’t have a chance of anticipating future threats if it never looks for them.