More Justice Department Precedent in Support of Mueller’s Obstruction Theory

An important debate is happening at Lawfare and elsewhere about Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s application of the obstruction of justice statutes to conduct by President Trump. Jack Goldsmith argues that Mueller’s analysis of the obstruction statutes does not stand up to close scrutiny. Benjamin Wittes argues that it does.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

An important debate is happening at Lawfare and elsewhere about Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s application of the obstruction of justice statutes to conduct by President Trump. Jack Goldsmith argues that Mueller’s analysis of the obstruction statutes does not stand up to close scrutiny. Benjamin Wittes argues that it does.

By way of background, the obstruction of justice statutes do not expressly state that they apply to the president. The most relevant statute, 18 U.S.C. § 1512(c), applies to “[w]hoever” corruptly interferes with an ongoing proceeding. The Mueller report concluded that this statute applied to Trump’s actions, and marshalled significant evidence that it was violated several times by the president.

Goldsmith, William Barr (while a private citizen) and others have made the argument that statutes like § 1512, which do not expressly apply to the president, must be construed as not constraining the president if such application would involve a possible conflict with the president’s constitutional prerogatives. They trace this clear statement rule primarily to a 1992 Supreme Court case—Franklin v. Massachusetts, which concluded that the president is not an “agency” under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA)—and several opinions by the Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel (OLC), including one issued in 1995. The purpose of this clear statement rule is to protect the constitutional prerogatives of the presidency.

Applying the clear statement rule is not tantamount to stating that it would be unconstitutional to prosecute a president for obstruction based on official acts facially authorized by Article II—though Barr and Trump’s private lawyers appear to believe this too. Rather, the point of the clear statement rule is that Congress, if it wants to cover the president with statutes like § 1512, needs to amend them to expressly cover the president. (If that occurred, then any future application of the amended statutes to the president would need to be evaluated case-by-case for constitutionality.)

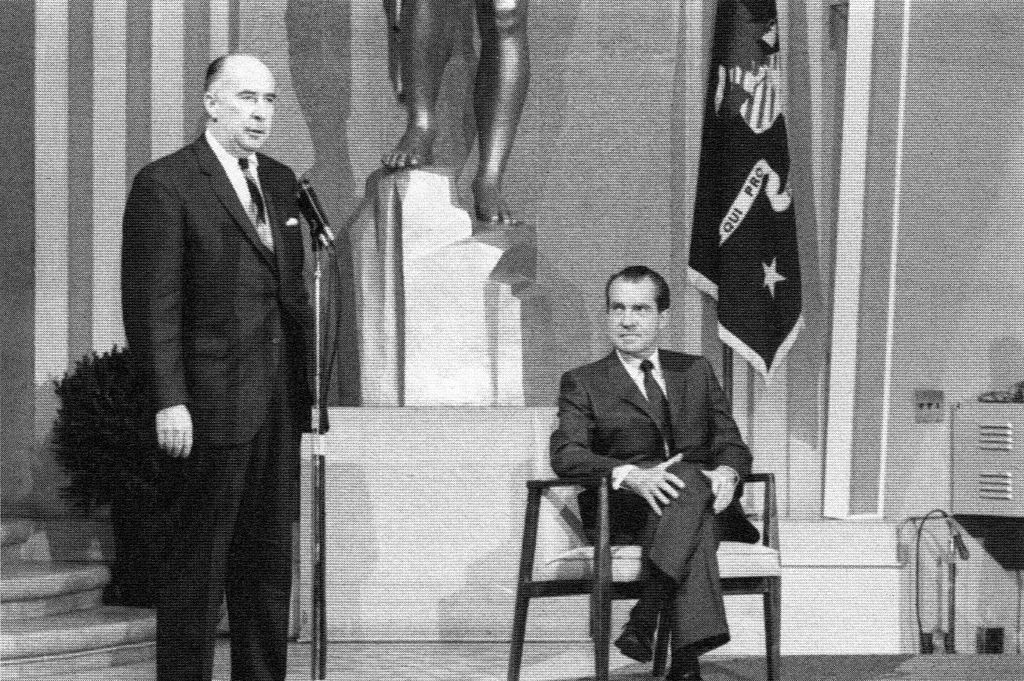

Wittes recently contested the view that Justice Department precedent uniformly cuts against Mueller’s view of the obstruction statutes. Wittes shows that previous investigators of potential obstruction by sitting presidents—Leon Jaworski investigating President Nixon, Lawrence Walsh investigating President Reagan and Kenneth Starr investigating President Clinton—did not appear to view their investigations as hampered by a clear statement rule:

[A]ll three investigated the presidents then in office for obstruction of justice in situations in which the matters in question touched their Article II management of the executive branch at least in some significant part. None, to my knowledge, took the view that the presidential plain statement rule precluded application of the obstruction statutes to presidential conduct.

Wittes argues persuasively that the OLC opinions relied upon by Goldsmith and Barr should be read alongside and in light of this other line of Justice Department precedent, which did not apply a clear statement rule to obstruction statutes. But additional Justice Department precedent supports Wittes in this debate.

After Clinton was impeached by the House for perjury and obstruction of justice, he was acquitted by the Senate in February 1999. As Clinton’s second term was approaching its end, in August 2000, OLC wrote an opinion for the attorney general entitled “Whether a Former President May Be Indicted and Tried for the Same Offenses for Which He Was Impeached by the House and Acquitted by the Senate.” OLC concluded that a president acquitted by the Senate in an impeachment trial may nevertheless be criminally prosecuted for the same conduct once he leaves office. Although clearly written on the backdrop of Clinton’s Senate acquittal for obstruction and perjury, the OLC opinion never mentioned that a clear statement rule would in fact prevent the indictment of former President Clinton for crimes such as obstruction of justice under 18 U.S.C. §§ 1503 or 1505, perjury under 18 U.S.C. § 1621, or witness tampering under 18 U.S.C. § 1512(b)—statutes that, like almost all federal crimes, do not specifically provide that they cover presidential misconduct. (The § 1512(c) obstruction provision was only enacted in 2002.) If OLC thought the clear statement rule would definitely or possibly bar prosecution of a former president, it seems odd that the office did not mention it.

Similarly, in October 2000, OLC issued an opinion on whether a sitting president may be criminally charged. In answering “no,” OLC reiterated the view that the Justice Department had earlier expressed during the Nixon crisis in 1973—in an OLC opinion and a brief filed by Solicitor General Robert Bork in the Spiro Agnew grand jury case—that a former president may be criminally prosecuted after leaving office for acts committed while in office. (Recall that the House Committee on the Judiciary approved articles of impeachment for Nixon that charged obstruction of justice.) Although the Franklin case and the 1995 OLC memo were already on the books, the 2000 OLC opinion, covering 39 pages, never suggested that a clear statement rule would require Congress to amend the criminal code expressly naming presidents as potential defendants before prosecution of a former president could occur.

Of course, pointing to a dog that didn’t bark can prove only so much. But the silence does seem notable here given the salience of presidential obstruction of justice, both with regard to Nixon and during Clinton’s second term when the two OLC opinions were written.

It makes good sense to exempt federal criminal statutes from the application of this clear statement rule. First, application of federal criminal law to in-office actions of a former president is under the total control of the Justice Department, arguably reducing the need for a clear statement rule. Only the department is legally authorized to bring such charges, and it is famously protective of the prerogatives of the presidency. This makes criminal law very different than, for example, application of the APA discussed by Franklin. If the APA applied to presidential action, private litigants and the federal judiciary would have the power to probe the inner workings of the White House, without any veto by the executive branch.

Second, criminal conduct by a sitting president is uniquely harmful to core constitutional values such as the rule of law, and only very strong reasons should justify putting the president above the law (unless reenacted by Congress with a clear statement, and thus subject to a veto). And third, as Daniel Hemel and Eric Posner have pointed out, the Supreme Court did not apply a clear statement in United States v. Nixon, the Oval Office tapes case. There the court unanimously upheld a subpoena from the Watergate special prosecutor to the president under Rule 17 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, a statute that applied to “person[s]” and did not specifically name the president. Nixon was decided prior to Franklin, however.

Fourth and finally, there are strong arguments that conduct by a president exercising Article II authorities that nevertheless violates certain core federal criminal statutes should in fact be viewed as ultra vires, unauthorized by Article II—and therefore not in need of a clear statement rule to protect it. OLC has taken this position with regard to bribery. The Mueller report, Wittes, Quinta Jurecic and others have made versions of this argument with regard to obstruction of justice.

I agree with both Goldsmith and Wittes that the Mueller report could have and should have said more about its statutory analysis, given the stakes and given the OLC and Supreme Court precedents on the clear statement rule. But I am not convinced at this point that Mueller committed any error beyond failing to offer a more detailed explanation. Similarly, the Mueller report could also have said more about the constitutional issues raised by applying obstruction of justice statutes to facially valid actions by the president—actions seemingly authorized by Article II that would be unlawful only if done with a corrupt intent. My view, which I hope to contribute soon to the public debate, is that Mueller was again correct and could have said much more in his own behalf.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to include more details about the specific obstruction statutes at issue.

-(1).png?sfvrsn=dd820f87_5)