The Mueller Report and ‘National Security Investigations and Prosecutions’

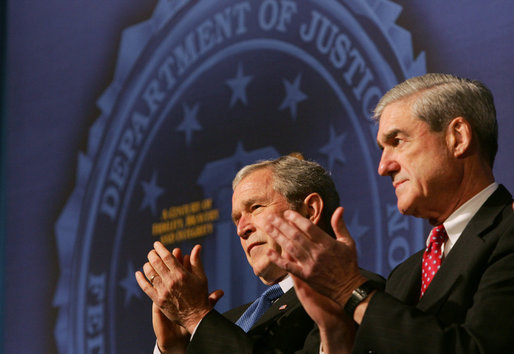

When Doug Wilson and I set out to write the first edition of “National Security Investigations and Prosecutions” (NSIP), the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, were still recent, George W. Bush was in his first term as president of the United States, Vladimir Putin was in his first term as the leader of Russia, Robert Mueller was director of the FBI and Lawfare was not even a gleam in its founders’ eyes.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

When Doug Wilson and I set out to write the first edition of “National Security Investigations and Prosecutions” (NSIP), the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, were still recent, George W. Bush was in his first term as president of the United States, Vladimir Putin was in his first term as the leader of Russia, Robert Mueller was director of the FBI and Lawfare was not even a gleam in its founders’ eyes.

Times have changed. As the third edition of our treatise goes on sale, al-Qaeda has proliferated but declined, the Islamic State has gained and lost control over vast territory in Syria and Iraq (and its leader has been killed by U.S. forces), domestic terrorism is on the rise, and new challenges and threats are now posed by nation-states including Russia, China, Iran and North Korea. The United States has chosen both Barack Obama and Donald Trump as president—the latter in an election aggressively attacked by Putin, who remains the leader of Russia. The Russian election attacks, and related misconduct, were investigated by Mueller—now in a new role as special counsel—whose last major public act may have been congressional testimony describing his report as “a signal, a flag to those of us who have responsibility to exercise that responsibility, not to let this kind of thing happen again.”

Recently, Lawfare’s editor in chief, Benjamin Wittes, asked me to unpack some of the material in NSIP that is relevant to L’Affaire Russe and the Mueller probe. Although we wrote the treatise in the thick of what used to be called the global war on terror, its descriptions and analyses apply broadly to national security investigations and prosecutions of all kinds. And the extended period of prepublication review required for the third edition is, I hope, a testament to our efforts to keep it current. All of the following material is drawn from different parts of the treatise.

Intelligence and Law Enforcement Investigations

When Robert Mueller was appointed as the special counsel, he was ordered to conduct “the investigation confirmed by then-FBI Director James B. Comey in testimony before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence on March 20, 2017.” This was an investigation that Comey described as follows (emphasis added):

I have been authorized by the Department of Justice to confirm that the FBI, as part of our counterintelligence mission, is investigating the Russian government’s efforts to interfere in the 2016 presidential election and that includes investigating the nature of any links between individuals associated with the Trump campaign and the Russian government and whether there was any coordination between the campaign and Russia’s efforts. As with any counterintelligence investigation, this will also include an assessment of whether any crimes were committed.

Unless you lived through the changes that made it true, you might not understand how significant it was for Comey to say that “any counterintelligence investigation” includes criminal law enforcement. Before 9/11, such a statement would have been impossible to make. This was due to the so-called Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) “wall” that kept intelligence and law enforcement personnel at arms’ length from one another, sometimes requiring two separate investigations of the same suspect—one by a squad of FBI intelligence agents, and the other by a squad of FBI law enforcement agents—with limited coordination between them. Two chapters of NSIP are devoted to how the FISA wall was built and then dismantled, and the constitutional questions raised by that dismantling. The treatise makes the case that the FISA wall was bad not only for national security but also for civil liberties and privacy. In other words, the fall of the wall was a rare win-win event, an escape from the traditional view that privacy and security are locked into a zero-sum game.

The treatise addresses in depth the FBI’s current internal guidelines for domestic activity that were made possible by the lowering of the FISA wall. These guidelines express the logic of what might be termed a post-9/11 mindset, in which three ideas are paramount.

First, the FBI is a security service, with combined law enforcement and intelligence/counterintelligence functions. Criminal prosecution is only one way that the bureau fulfills its mission. The FBI is not limited to “investigation” in the narrow sense of focusing on solving a particular crime, but it may also conduct proactive assessments and collect information for broader analytic purposes. Among the non-law enforcement remedies mentioned in the FBI guidelines, and discussed in NSIP, are “‘excluding or removing persons from the United States; recruitment of double agents; freezing assets[,] ... securing targets[,] ... providing threat information and warnings[, and] ... diplomatic or military actions; and actions by other intelligence agencies.’” One chapter of the treatise compares in extensive detail the main characteristics of civilian law enforcement, prosecution before a military commission and detention under the law of war, and assesses the use of civilian prosecution as an intelligence-collection platform.

Second, “to a degree that is notable even for the FBI”—as NSIP affectionately puts it—the guidelines “repeatedly assert” the bureau’s “authority and status as the lead federal agency in the fields of federal law enforcement, counterintelligence, and (within the United States) affirmative foreign intelligence.” And the guidelines make clear that these individual “strands of authority” are “braided,” meaning that the FBI’s “‘information gathering activities’ need not be ‘differentially labeled’ as law enforcement, counterintelligence, or affirmative foreign intelligence, and its personnel need not be ‘segregated from each other based on the subject areas in which they operate.’” NSIP explains how the FBI’s concerns about possible loss of autonomy to the director of national intelligence (DNI), and interagency competition with the Department of Homeland Security, significantly improved the relationship with its parent agency, the Department of Justice, which had been significantly tense in years past.

Indeed, the third major idea reflected in the FBI guidelines is a greater degree of connection between the FBI and the Justice Department, including through oversight of the former by the latter. NSIP explains how, even after the revelation of abuses and reforms in the mid-1970s, the FBI’s national security elements continued successfully to resist almost all efforts at supervision by the department. Although agents and prosecutors began to work more closely together in increasingly complex criminal matters during the 1970s—many of them involving organized crime—the FBI remained largely independent in its counterintelligence work, conducting investigations without the same level of involvement by Justice Department attorneys. This was a handicap, because agents in general were “trained with the expectation that they would work cooperatively with lawyers” in complex investigations. Over time, however, FBI agents and lawyers in the Justice Department’s National Security Division have developed much stronger relationships, improving the effectiveness of their work in counterintelligence as well as law enforcement.

Ironically, although Mueller was charged with conducting a hybrid investigation of the sort made possible by the demise of the FISA wall, he focused almost exclusively on law enforcement and left the traditional counterintelligence work to others. That is why, for example, he emphasized “conspiracy” rather than “collusion” between the Trump campaign and Russia. It is also why his report explains (Vol. 1, p. 13) that his office met “regularly” with the “FBI’s Counterintelligence Division” to pass any “foreign intelligence and counterintelligence information relevant to the FBI’s broader national security mission.” For some observers, Mueller’s focus on criminal law was a significant flaw in his undertaking. For him, it may have seemed the only way to manage the workload, particularly given what he described as the ongoing nature of Russian efforts. The Justice Department regulations governing special counsels, many of which applied to Mueller, may also have exerted some influence on his approach: They are clearly written without reference to counterintelligence concerns, considering possible presidential misconduct solely through the lens of domestic law enforcement.

Investigative Tools: Wiretapping and More

Mueller’s report (Vol. 1, p. 13) describes the use of several law enforcement investigative tools, including “more than 2,800 subpoenas under the auspices of a grand jury[,] ... nearly 500 search-and-seizure warrants[,] ... more than 230 orders for communications records” under the criminal Stored Communications Act, and “almost 50 orders authorizing use of pen registers.” And NSIP has chapters addressing each of these investigative tools, as well as others, including mail covers, national security letters, tangible things orders and material witness warrants. The treatise is designed authoritatively to cover every tool in the toolbox for national security investigations in this country.

Although Mueller’s report does not describe the use of any foreign intelligence investigative authorities, such as FISA, it cites prior work by the intelligence community, including the January 2017 assessment discussed below. We also know, from the disclosures concerning former Trump campaign official Carter Page, that FISA was used before Mueller took over, and Mueller’s report has a section devoted to Page and his interactions with Russia (Vol. 1, pp. 95-103). But few readers of the Mueller report will have a significant understanding of how the United States regulates national security wiretaps that might have been useful in discovering Russian election interference. This is important as the Justice Department inspector general gets ready to issue a major investigative report focused, in part, on the handling of the Carter Page FISA application.

The treatise has chapters on the history of electronic surveillance going back to the U.S. Civil War, when telegraph wires were tapped to learn military plans; an overview of FISA; a description of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISA Court) and Court of Review, which review applications for FISA wiretaps; a deep dive into the nuts and bolts of FISA applications; a really deep dive into FISA’s definitions of “electronic surveillance” and “physical search” and other key terms in the law; an explanation of FISA “minimization,” the set of rules that requires the government to balance its need for intelligence against the privacy rights of Americans in the conduct of wiretaps and searches; and an extensive discussion of congressional oversight, including the challenges of conducting secret intelligence work in a democracy dependent on the rule of law and public debate. It also has a chapter on FISA’s criminal and civil provisions that focus on certain violations of the statute when committed “under color of law”—for example, violations committed by government personnel acting in their official capacities.

Reviewing these materials in NSIP allows for an informed evaluation of disputes about contemporary topics related to the Mueller investigation, including the minimization (known as masking) of U.S. person information in FISA wiretaps that acquired conversations between Russian officials and former Trump National Security Adviser Michael Flynn. Likewise, the treatise provides the background necessary to assess the shenanigans of former House Intelligence Committee Chairman Devin Nunes and how the FISA Court likely reviewed the FISA applications on Page.

The treatise also addresses the “modernization” of FISA, which, along with the lowering of the FISA wall, is one of the most significant changes in national security law in the past 20 years. Three chapters of NSIP are devoted to the story of FISA modernization, the updating of the statute that culminated in the FISA Amendments Act of 2008 (FAA). These chapters review President Bush’s decision, immediately after the Sept. 11 attacks, to authorize foreign intelligence surveillance outside of FISA, the political and legal firestorm that created, and the eventual enactment of the FAA by Congress.

Political scientists, as well as lawyers, may find it interesting to compare the lowering of the FISA wall to the modernization of FISA, and to focus on what the comparison reveals about how law changes. The FISA wall was a known problem in the Department of Justice for many years, albeit one without any conceptual, legal or politically viable solution. After 9/11, the problem was solved by a combination of coordinated legislative, executive, and judicial action, with Congress passing a law, the executive adopting procedures implementing that law, and the courts first rejecting and then accepting the government’s procedures in a published judicial decision in November 2002.

The path to FISA modernization, by contrast, was first addressed by the executive branch in secret, through the Terrorist Surveillance Program (TSP). The TSP was conducted by the National Security Agency (NSA) with presidential authorization and subject to limited congressional briefings and notice to (but not request for approval from) the presiding judge of the FISA Court. When it was discovered and revealed publicly by the New York Times in late 2005, the TSP ignited a firestorm of controversy. Later, the government tried to bring the TSP collection under FISA by making an application to the FISA Court. The court briefly approved, but then forcefully disapproved, the collection. Having pursued executive and judicial solutions in sequence, the Bush administration decided to engage with the third and final branch of government—Congress—resulting in a legislative solution in 2007 that turned out to be a failure and had to be rewritten the following year but has endured since then. Again, for those who want to understand how major legal change takes place in government, these two case studies make an interesting contrast.

The U.S. Intelligence Community

For many people who followed the Russia story, the first exposure to an authoritative description of Russian election interference came from the Intelligence Community Assessment, released in January 2017, just before President Trump’s inauguration. The assessment’s headline was, and remains, stark:

We assess Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered an influence campaign in 2016 aimed at the US presidential election. Russia’s goals were to undermine public faith in the US democratic process, denigrate Secretary Clinton, and harm her electability and potential presidency. We further assess Putin and the Russian Government developed a clear preference for President-elect Trump. We have high confidence in these judgments.

The assessment described itself as including “an analytic assessment drafted and coordinated among The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and The National Security Agency (NSA), which draws on intelligence information collected and disseminated by those three agencies …. When we use the term ‘we’ it refers to an assessment by all three agencies.”

Pause a minute over the “we” in the intelligence community’s assessment. While the National Security Act of 1947 combined the Army, Navy, and Air Force under a single cabinet officer—the secretary of Defense—there remain many other federal agencies and officials with significant roles relating to national security. For reasons historical, political and legal, there is no U.S. “Department of National Security” or “Department of Intelligence.” Instead, the U.S. has a “community” of 17 separate elements in the government that are responsible for various aspects of intelligence and national security, each of which is discussed and assessed in NSIP. This large intelligence community is nominally led by a DNI and superintended by a National Security Council (NSC) at the White House.

The DNI position is currently vacant due to the departure of Dan Coats and his principal deputy, but NSIP describes the position in detail, including how it has evolved from its immediate predecessor, the director of central intelligence. The treatise observes that the “first DNI, John Negroponte, relinquished the position in early 2007 to become Deputy Secretary of State—a move which may have reflected his preference for a diplomatic posting, but which nonetheless suggested that the DNI position was less attractive than a second tier posting at another agency.” The treatise raises hard questions about the position, including whether “the DNI, as one of many cabinet-level officers, can effectively coordinate and control the actions of other cabinet-level officers,” such as the secretary of defense, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, and the director of the FBI, or “whether as a practical matter the major functions envisioned for the DNI can only be exercised from the White House itself and the NSC, which stands above the Departments and Agencies.”

NSIP also reviews the origins and evolution of the NSC, describing how it has been a “flexible” institution, “responding to the preferences of individual Presidents.” Reviewing the organization and function of the NSC from Presidents Truman to Trump, the treatise allows readers to assess more recent developments, including Trump’s short-lived effort to include his political chief strategist, Steve Bannon, as part of the council. It also provides context and background necessary to understand exactly why Trump’s decision was so radical.

Another vitally important aspect of the U.S. intelligence community that shows up repeatedly in discussions of the Mueller investigation is how and why the community is regulated. The treatise takes a historical approach to this question, beginning with the 30-year period in which the intelligence community was effectively not regulated at all, and the truly horrific abuses that ensued. We describe those abuses unstintingly: “Beginning after World War II, the Intelligence Community conducted investigations, and otherwise gathered information, in ways that systematically broke the law. Abuses included routine opening and reading of vast amounts of first-class mail and telegrams and drug experiments conducted on unwitting American subjects.”

The treatise also explores the vitally important question of why these abuses occurred (footnotes omitted):

A modern reader may reasonably ask what motivated the abuses. Were hundreds or thousands of U.S. Government employees simply arrant sadists? Were they petty tyrants drunk on power? A review of the historical record suggests that their excesses were motivated in substantial part by fear. For example, the CIA believed, in the aftermath of World War II, that the Soviet Union was engaged in a wide-ranging program of testing LSD. It genuinely thought that the Soviets might develop mind-control drugs and turn every American into an obedient, Communist zombie. One CIA officer testified that he and his colleagues were “literally terrified” at the prospect. Charged with the solemn obligation to keep the country safe, they were prepared to take desperate measures. Unconstrained by any real system of limiting rules and oversight ... in fact they did so.

The purpose of this historical review is not to disparage the intelligence community but, rather, to explain the foundations of the current regulatory regime. For example, the principal executive order for the intelligence community today provides that no element “shall sponsor, contract for, or conduct research on human subjects except in accordance with guidelines issued by the Department of Health and Human Services.” This provision is literally inexplicable without reference to the CIA’s historical program of using LSD on unwitting Americans, including individuals randomly picked up in bars and brought to CIA safe houses for secret testing. The treatise reviews this abuse, its revelation in the mid-1970s and the resulting paradigm of intelligence under law on which the country continues to rely.

Beginning in 2009, when I was assistant attorney general for national security at the Department of Justice, I required all of our new attorneys to read excerpts from the 1976 Senate report that documented many of the intelligence community’s abuses. I thought it was important for those exercising governmental power to be reminded of prior abuses of that power and to understand the reason for the regulations that constrained them. For similar reasons, I cover this material when I teach national security law today.

As presented in NSIP, the historical review is designed not only to remind readers and practitioners of what can go wrong but also to serve as a frame of reference for assessing more recent transgressions. There is a real difference, at least in my mind, between an organized program of intentional law-breaking, complete with high-level contingency plans for a cover-up, and repeated but good-faith compliance violations reported semiannually to Congress. As reprinted in NSIP, here is an excerpt from a high-level, internal CIA memorandum from 1962, concerning the agency’s program of opening and reading Americans’ first-class letters:

Since no good purpose can be served by an official admission of the violation, and existing Federal statutes preclude the concoction of any legal excuse for the violation, it must be recognized that no cover story is available to any Government Agency …. Unless the charge is supported by the presentation of interior items from the Project, it should be relatively easy to “hush up” the entire affair …. Under the most unfavorable circumstances, it might be necessary ... to find a scapegoat to blame for unauthorized tampering with the mails.

Recognizing the extremes of the past allows for more serious engagement with the challenges of the present. If Donald Trump’s presidency has been an exercise in defining deviancy down, NSIP also explains how the country came together in the mid-1970s to define it up.

Today’s paradigm of intelligence under law, and associated oversight by Congress and other entities, is part of why some Lawfare commentary predicted that Trump would have better luck suborning law enforcement than intelligence. For example, here is Wittes writing in May 2016: “Let me be blunt: The soft spot is not NSA and it’s not the drone program. The soft spot, the least tyrant-proof part of the government, is the U.S. Department of Justice and the larger law enforcement and regulatory apparatus of the United States government.” I have written recently about how intelligence under law and associated institutions at the Justice Department are resilient but should not be tested as they are being tested today.

***

This is a confused time for America in general and for national security in particular. Contemporary debates often generate more heat than light. In part that may be because illuminating debate requires so much hard work, not in the least because there must be a foundation of shared—or at least mutually recognizable—factual and analytic understanding that can support productive disagreement. It is my belief, and hope, that NSIP can contribute some part of that foundation in an area of vital interest and importance to the country.

All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official positions or views of the U.S. Government. Nothing in the contents should be construed as asserting or implying U.S. Government authentication of information or endorsement of the author’s views.

-final.png?sfvrsn=b70826ae_3)