Must Bill Barr Abide Ethics Advice on Recusal? A Debate

The two of us tend to agree on most things. Perhaps it is a result of our similar backgrounds, as career federal prosecutors who worked in the field and came up through the ranks to be United States attorneys. We often compare notes in our current roles as MSNBC analysts, trying to digest and explain complicated news in a thoughtful way.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The two of us tend to agree on most things. Perhaps it is a result of our similar backgrounds, as career federal prosecutors who worked in the field and came up through the ranks to be United States attorneys. We often compare notes in our current roles as MSNBC analysts, trying to digest and explain complicated news in a thoughtful way.

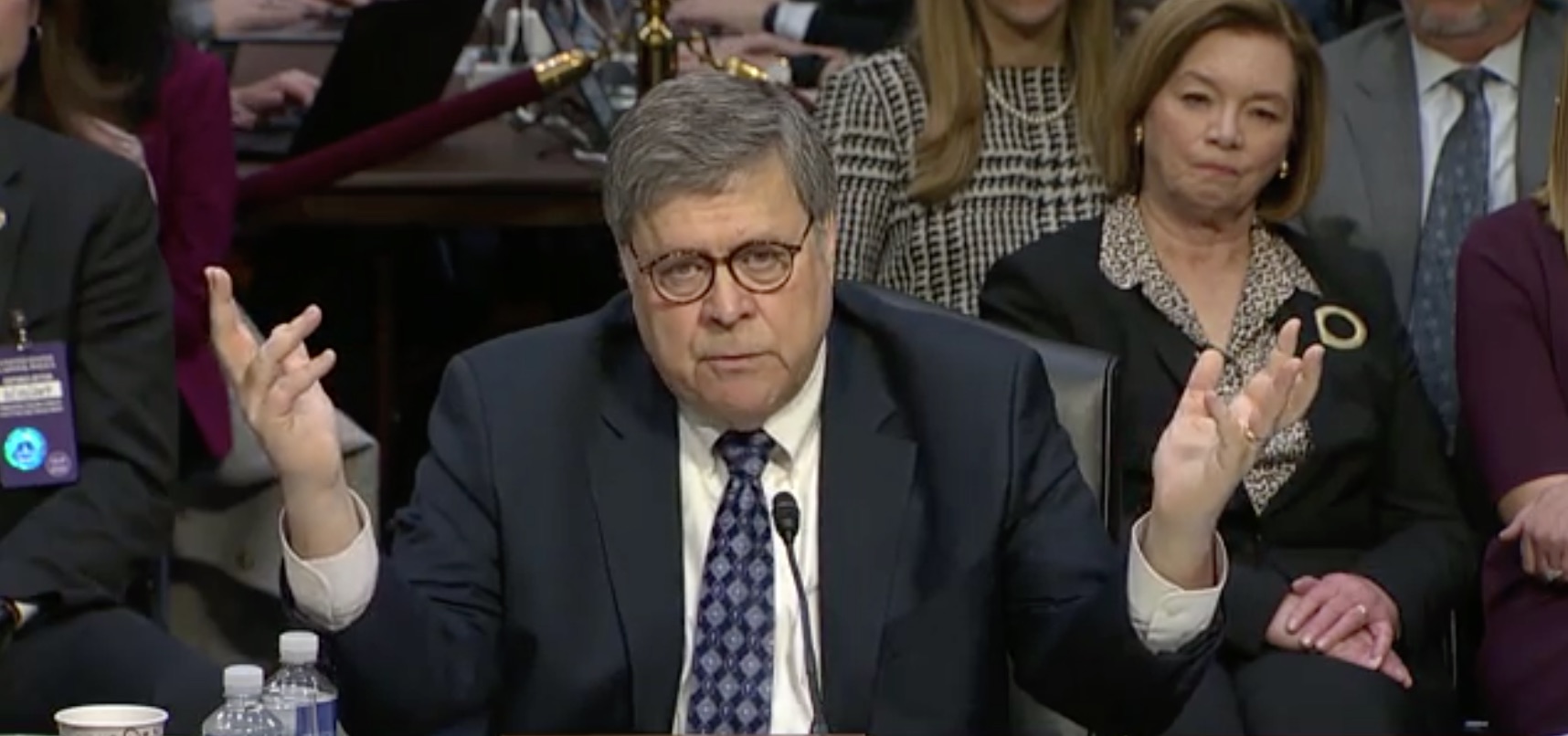

But we respectfully disagree on an important point that surfaced during Attorney General-nominee Bill Barr’s confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee on January 15 and 16: whether, if confirmed, he should agree to abide ethics advice from Justice Department officials, before he receives that advice, regarding whether to recuse himself from supervision of the Mueller investigation.

Barr previously criticized the Mueller probe, including in an unsolicited legal memo he circulated to the Justice Department and President Trump’s legal team in the spring of 2018, and he commented favorably on the merits of investigating Hillary Clinton for what seems to us to be a bogus accusation. During his hearing, Barr was asked whether he would seek ethics advice regarding recusal. He said he would. When asked whether he would follow that advice, he said that as “head of the agency,” he would make the decision as to his own recusal. He would not follow that ethics advice, he said, if he “disagreed” with it. Is that appropriate? McQuade says no; Rosenberg says yes.

The Justice Department has a strict set of rules and norms that govern recusals. In some cases—for instance, where a prosecutor has a political, financial, or familial interest in a matter—a recusal is mandatory. Other situations can give rise to an appearance of a conflict—a set of conditions that call into question a prosecutor’s impartiality. In those cases, a prosecutor might be advised to recuse, but it is not mandatory. We both believe it is crucial that the work of the Justice Department be impartial and that it appear to be impartial. Thus, we believe that these recusal rules should be scrupulously followed. So far, so good.

We also agree that the career ethics professionals at the Justice Department are a tremendous resource—smart, experienced and non-partisan. It is wise to seek and follow their advice, and we both routinely did so when we were prosecutors. Anyone who ignores their advice does so at their professional, reputational, and personal peril. Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions sought their guidance and followed it, recusing himself from supervision of the Russia investigation, while current Acting Attorney General Matthew Whitaker sought their advice and ignored it. As a result, Whitaker remains in charge of the Mueller probe today. Sessions, we both agree, made the right choice and Whitaker the wrong one, given his prior multiple pronouncements on the legitimacy of the investigation. When in doubt, Justice Department officials should recuse.

McQuade’s Case Against Barr’s Stance

McQuade believes Barr is right to promise to seek the advice of career ethics officials, but wrong to refuse to commit up front to complying with that advice. What is the point of seeking ethics advice if only to ignore it? Barr seems to be saying that he will consider the recommendation of ethics officials but that, ultimately, he will decide whether to recuse himself. While this buck-stops-here approach makes sense in many aspects of an attorney general’s work, and maybe even in some cases of recusal, it fails here.

By his own actions, Barr has put his impartiality into question. In addition to submitting the memo, in which he prejudged a potential legal theory, he also met with Trump to discuss representing him as his personal lawyer. And Peter Baker of the New York Times has revealed that in a 2017 email message, Barr disparaged the investigation into what he referred to as “so-called ‘collusion,’” saying that it was less worthy of investigation than Hillary Clinton and the uranium deal or the Clinton Foundation. These facts have rightly raised concerns over Barr’s objectivity and independence.

If ethics officials recommend recusal and Barr continues to oversee the investigation nonetheless, then his role in the case will be tainted in the public eye. To that point, if Barr ultimately clears Trump and his associates, his decision will be questioned by the public and will forever bear a figurative asterisk. If, on the other hand, he obtains approval from ethics officials to proceed and ultimately comes to the same conclusion, then the public can have confidence in the process. In light of the magnitude and sensitivity of the case, Barr’s conduct and Trump’s demonstrated disdain for the independence of the Department of Justice, agreeing to follow the advice of ethics officials is the only way to provide public confidence in any decision that Barr makes as attorney general regarding the Mueller probe.

Rosenberg’s Case in Favor of Barr’s Stance

Rosenberg believes Barr must seek the advice of career ethics officials, as he promised he would. Then, assuming the situation is not one in which recusal would be mandatory, and once Barr has all the facts and all the input from ethics officials—he should decide whether or not he will recuse, as he said he would do at the hearing. As attorney general, his job will be to surround himself with the best, smartest, and most experienced personnel, to solicit and carefully consider their advice, and to make the best decision he can based on the law, facts, rules, procedures and norms of the Justice Department. His job is not to solicit advice and follow it; it is to solicit advice and decide whether that advice is sound, as the judgment of career ethics officials normally is. He (or any attorney general, for that matter) is hired (by any president and any Senate) to exercise his best judgment.

Sessions, for instance, was right to solicit ethics advice, but wrong to agree in advance to follow it, particularly when he did not know what it—or the rationale for it—would be. For instance, if career ethics officials had advised Sessions that he did not need to recuse (though it is hard to imagine they would say that), and he followed that advice, the process would have been correct but the outcome would have been wrong. That said, Sessions got to the correct answer—he was right to recuse himself from supervising the Mueller probe given the political role he played in Trump’s campaign. Whitaker was right to solicit ethics advice, but wrong to ignore it, particularly given the numerous partisan and disparaging statements he made about the Mueller probe.

Imagine if at his confirmation hearing, Barr had been asked about a sensitive case pending in a federal court—a case in which certain senators believed the Justice Department had taken an improper position or in which those lawmakers desired a certain outcome. Imagine, too, if he had been asked whether, if confirmed, he would get briefed on the case by career Justice Department attorneys and follow their advice, regardless of what it was, on how to proceed. His answer in that case should be “no”: “I do not know the facts. I will solicit their advice. I welcome their advice. I will give great deference to their advice. But, if confirmed, I will be in charge and I will decide.” That is manifestly the role of an attorney general. If he is wrong, then he can answer for it.

***

With the independence of the Justice Department and the legitimacy of law enforcement under attack from the president, the stakes for Barr's choice are significant. We both believe it is crucial that Barr make the right decision. We just think that there are different paths to get there.