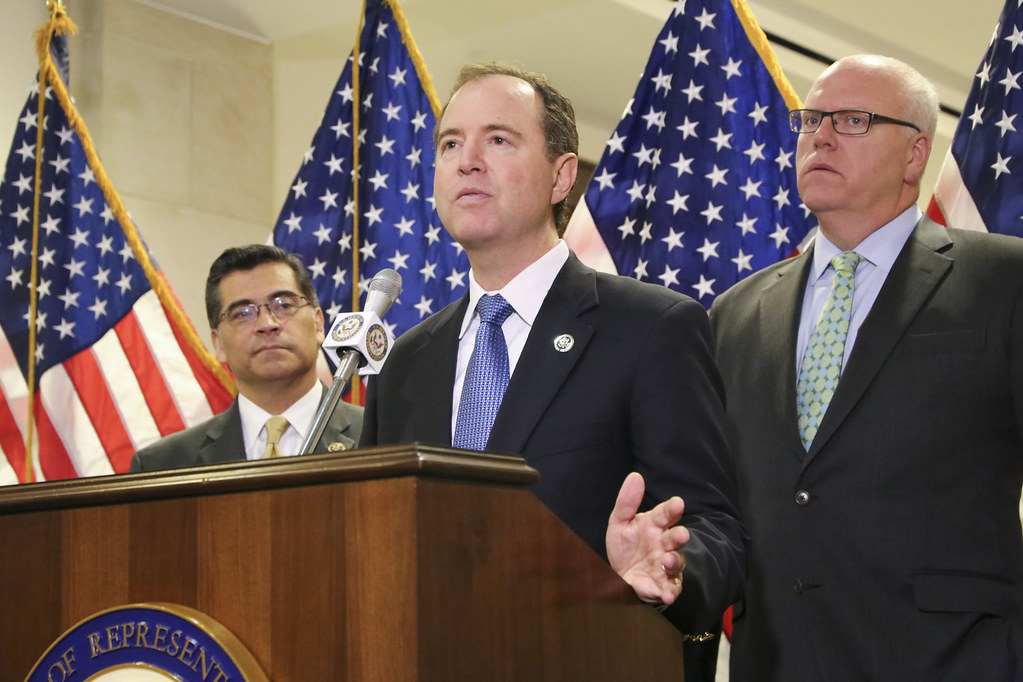

The Mysterious Whistleblower Complaint: What Is Adam Schiff Talking About?

On Sept. 13, House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff issued a subpoena to Acting Director of National Intelligence Joseph Maguire to compel the production of a whistleblower complaint.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On Sept. 13, House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff issued a subpoena to Acting Director of National Intelligence Joseph Maguire to compel the production of a whistleblower complaint. The details of the complaint remain vague, but Schiff stated that it was filed by an individual in the intelligence community and determined by Intelligence Community Inspector General Michael Atkinson to be credible and a matter of “urgent concern.” Schiff’s subpoena also demands the text of the inspector general’s determination regarding credibility and all records pertaining to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s (ODNI’s) involvement in the matter, including correspondence with other executive branch actors. If Maguire does not comply, Schiff has indicated the committee plans to require him to appear before the committee in an open hearing on Thursday.

How did the committee arrive at this point, and what might happen next?

The Statutory Framework

The Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act (ICWPA) of 1998 was the first whistleblower legislation specific to the intelligence community, specifying a process for an intelligence community whistleblower to make a complaint. A decade later, the Intelligence Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 added general provisions for protecting intelligence community whistleblowers. Presidential Policy Directive 19, signed by President Obama in 2012, provided the first specific protections for intelligence community whistleblowers, and the Intelligence Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014 codified those provisions.

The relevant part of the law, codified at 50 U.S.C. §3033, provides that:

An employee of an element of the intelligence community, an employee assigned or detailed to an element of the intelligence community, or an employee of a contractor to the intelligence community who intends to report to Congress a complaint or information with respect to an urgent concern may report such complaint or information to the Inspector General. (Emphasis added.)

The law requires the intelligence community inspector general to report all complaints the inspector general finds credible to the director of national intelligence (DNI) within 14 days. Thereafter:

Upon receipt of a transmittal from the Inspector General ... the Director shall, within 7 calendar days of such receipt, forward such transmittal to the congressional intelligence committees, together with any comments the Director considers appropriate. (Emphasis added.)

The statute defines “urgent concern” as any of the following:

(i) A serious or flagrant problem, abuse, violation of law or Executive order, or deficiency relating to the funding, administration, or operation of an intelligence activity within the responsibility and authority of the Director of National Intelligence involving classified information, but does not include differences of opinions concerning public policy matters.

(ii) A false statement to Congress, or a willful withholding from Congress, on an issue of material fact relating to the funding, administration, or operation of an intelligence activity.

(iii) An action, including a personnel action described in section 2302(a)(2)(A) of title 5, constituting reprisal or threat of reprisal prohibited under subsection (g)(3)(B) of this section in response to an employee’s reporting an urgent concern in accordance with this paragraph.

The statute also provides a path for the whistleblower to submit a complaint or information directly to Congress in the event the intelligence community inspector general either (1) does not find the complaint or information credible or (2) does not transmit the complaint or information to the director “in accurate form.” In that case, the whistleblower may inform Congress directly but must inform the inspector general and “obtain[] and follow[] from the Director, through the Inspector General, direction on how to contact the congressional intelligence committees in accordance with appropriate security practices.”

The Facts

According to Schiff, on Aug. 12 an individual (it’s not public who) in the intelligence community submitted to the inspector general a whistleblower disclosure intended for Congress. The inspector general determined that the disclosure was credible and qualified as an “urgent concern,” and on Aug. 26—exactly 14 days after receiving it—transmitted to Maguire the whistleblower disclosure together with his determination on the disclosure’s credibility and urgency.

According to letters written by Schiff to Maguire, it appears Maguire did not transmit the disclosure to the committee—as he was required to do under the statute—within seven days. Nor did he notify the committee about the disclosure or his decision not to transmit it to the committee.

On Sept. 9, Inspector General Atkinson apparently wrote a letter (which has not been made public) directly to Schiff and the Intelligence Committee’s ranking member, Devin Nunes, informing them of his determination regarding the complaint. (Notably, the inspector general appears to have written this letter to Schiff under his own general authority rather than under authority delegated by the whistleblower statute: This type of letter is not contemplated by the statute, which does not contemplate noncompliance by the DNI with the seven-day reporting requirement to the congressional committees.)

On Sept. 10, Schiff wrote a letter to Maguire indicating Schiff’s awareness of the disclosure, stating that Maguire had not followed the law and demanding that Maguire forward the whistleblower transmittals from the inspector general to the congressional intelligence committees “without delay and in their entirety.” The letter made clear that if Maguire did not comply immediately, a subpoena would be forthcoming. Schiff demanded that Maguire provide the whistleblower, through the inspector general, any necessary direction on appropriate security procedures for the whistleblower to contact the committee directly. It is not entirely clear from the face of the statute that this provision is applicable: The provision applies when the inspector general does not find a complaint or information to be credible, but in this case Atkinson did.

On Sept. 13, Schiff wrote another letter to Maguire, referencing a discussion with him on Sept. 12 and providing the promised subpoena (which has not been made public), indicating that Maguire has “neither the legal authority nor the discretion to overrule a determination” by the inspector general and does not “possess authority to withhold from the Committee a whistleblower disclosure from within the Intelligence Community that is intended for Congress.” The letter indicates that Maguire’s office “has attempted to justify doing so based on a radical distortion of the statute that completely subverts the letter and spirit of the law, as well as arrogates to the Director of National Intelligence authority and discretion he does not possess.” A key paragraph of the letter states:

Even though the disclosure was made by an individual within the Intelligence Community through lawful channels, you have improperly withheld that disclosure on the basis that, in your view, the complaint concerns conduct by someone outside of the Intelligence Community and because the complaint involves confidential and potentially privileged communications. In a further departure from the statute, your office consulted the Department of Justice about the complaint, even though the statute does not provide you discretion to review, appeal, reverse, or countermand in any way the [intelligence community inspector general]’s independent determination, let alone to involve another entity within the Executive Branch in the handling of a whistleblower complaint. Your office, moreover, has refused to affirm or deny that officials or lawyers at the White House have been involved in your decision to withhold the complaint from the Committee. You have also refused to rule out to me that the urgent concern, and underlying conduct, relates to an area of active investigation by the Committee.

The letter also indicates that Maguire refused to provide the whistleblower with direction, through the inspector general, on how to contact the committee directly in a secure manner.

Late that night, officials in Maguire’s office acknowledged Schiff’s subpoena, indicating that “[w]e are reviewing the request and will respond appropriately” and that “[t]he ODNI and Acting DNI Maguire are committed to fully complying with the law and upholding whistleblower protections and have done so here.”

According to Schiff, he received a response from Maguire sometime after this letter, and Maguire indicated that he was not responding based on a command from a “higher authority” because it involves an “issue of privileged communications.” Schiff surmised that it was fair to conclude that it involves the president, people around the president, or both.

Analysis

As Marty Lederman and Robert Litt have pointed out, it has been the long-standing view of the executive branch that this and similar statutes must be read to give the president the final word on whether and how classified information will be provided to the congressional intelligence committees. In 1996, the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel issued a memorandum addressing the issue of classified disclosures to Congress and congressional authority to legislate in this space. The memo asserted that no act of Congress may “divest the President of his control over national security information in the Executive Branch by vesting lower-ranking personnel in that Branch with a ‘right’ to furnish such information to a Member of Congress without receiving official authorization to do so.”

The version of the 1998 bill introduced in the House, H.R. 3829, would have allowed the heads of agencies to decide not to transmit an employee’s complaint to the intelligence committees, or allow the employee to contact the committees directly, “in the exceptional case and in order to protect vital law enforcement, foreign affairs, or national security interests.” The agency head would have been required to provide the committees with the reason for such withholding within seven calendar days. At the time, the Office of Legal Counsel stated its view that the Senate version of the bill, which did not include this provision, was unconstitutional, publishing a lengthy argument based on separation of powers concerns.

But the House Intelligence Committee deleted this provision from the bill following extensive hearings. The committee expressly rejected, in the committee report, the administration’s argument that the bill was unconstitutional without that provision:

Like the Senate, the committee rejects the administration’s assertion that, as Commander in Chief, the President has ultimate and unimpeded constitutional authority over national security, or classified, information. Rather, national security is a constitutional responsibility shared by the executive and legislative branches that proceeds according to the principles and practices of comity. Nor does the Committee accept that the President, as Chief Executive, has a constitutional right to authorize all contact between executive branch employees and Congress…. The committee, in sum, finds no basis in the Constitution for a requirement that the President, either as Commander-in-Chief or as Chief Executive, approve any disclosure to Congress of information about wrongdoing within the executive branch.

Instead, the committee urged the executive branch, in disputes over the control and handling of classified information, to join in a spirit of “dynamic compromise”—a notion that had been articulated by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in its 1977 case United States v. AT&T. In that case, the FBI sent letters to AT&T requesting that certain American citizens be placed under electronic surveillance. The relevant House committee requested those letters and other documents, but President Ford refused to provide them, claiming national security concerns. After two years of interbranch negotiation and litigation, the circuit court steadfastly refused to side with either branch and encouraged further negotiation and compromise. The court acknowledged that the Constitution is largely silent on the question of allocation of powers associated with foreign affairs and national security, and stated that:

the coordinate branches do not exist in an exclusively adversary relationship to one another when a conflict in authority arises. Rather, each branch should take cognizance of an implicit constitutional mandate to seek optimal accommodation through a realistic evaluation of the needs of the conflicting branches in the particular fact situation. This aspect of our constitutional scheme avoids the mischief of polarization of disputes.

Ultimately, the executive and legislative branches agreed on a procedure whereby committee counsel received certain intelligence memoranda and, in December 1978, the parties to the dispute agreed to dismiss the case. (Mark Rozell describes the case in depth in his book “Executive Privilege: Presidential Power, Secrecy, and Accountability.”)

According to the 1998 House committee report, the notion of cooperation through dynamic compromise has been used to address the issue of accommodation on laws related to the handling of national security-related information for decades. (This report was incorporated by reference as the legislative history for the final version of the ICWPA, which was a title within the larger intelligence authorization bill enacted that year.) The committee considered the limitation of the reporting requirements to “particularly flagrant or serious” problems—a standard that already existed in inspector general statutes for the intelligence community—to represent this type of dynamic compromise. The fact that the whistleblower complaint or information went through the agency head rather than directly to Congress from the whistleblower represented another such compromise. The report concluded:

The committee believes that it must have access to those employees of the [intelligence community] who are aware of information, classified or otherwise, exposing corruption, mismanagement, or waste within their agencies or elements. The committee's statutorily established oversight responsibilities cannot be effectively carried out if employees are required to obtain the approval of the heads of their agency before exposing wrongdoing, mismanagement, or waste. H.R. 3829 as reported is an effort to accommodate the critical interests of national security, law enforcement, and foreign affairs and still accomplish that legislative mandate.

In other words, the committee considered the limitations and changes in the legislation itself to effectuate the appropriate type of compromise between the branches.

But the executive branch sought to give itself more flexibility. Upon signature of the ICWPA in 1998, President Bill Clinton issued a signing statement that included the following:

Finally, I am satisfied that this Act contains an acceptable whistleblower protection provision, free of the constitutional infirmities evident in the Senate-passed version of this legislation. The Act does not constrain my constitutional authority to review and, if appropriate, control disclosure of certain classified information to the Congress. I note that the Act's legislative history makes clear that the Congress, although disagreeing with the executive branch regarding the operative constitutional principles, does not intend to foreclose the exercise of my constitutional authority in this area.

The Constitution vests the President with authority to control disclosure of information when necessary for the discharge of his constitutional responsibilities. Nothing in this Act purports to change this principle. I anticipate that this authority will be exercised only in exceptional circumstances and that when agency heads decide that they must defer, limit, or preclude the disclosure of sensitive information, they will contact the appropriate congressional committees promptly to begin the accommodation process that has traditionally been followed with respect to disclosure of sensitive information. (Emphasis added.)

The Obama administration echoed Clinton’s position when changes were made to the law in 2010.

It seems the two branches were not on the same page when this legislation passed. The legislative branch considered the limitations in the statute itself to constitute the appropriate interbranch compromise on the question of the president’s constitutional authority to protect classified information. The executive branch, however, reserved for itself the potential for a broader, nonspecific, second bite at the apple when “sensitive information” is involved. Presidents Clinton and Obama did, however, signal that agency heads would decide whether they must defer, limit or preclude the disclosure of sensitive information, and that they would contact the appropriate congressional committees “promptly” to begin the traditional accommodation process.

In the current circumstances, so far the Trump administration is honoring neither the letter of the law nor the spirit of good faith cooperation that the relevant case law contemplates. Maguire seems not to have notified the committee, in any form, that a credible issue had arisen. He blew through the statutory deadline with seemingly no attempt to communicate with the committee. It seems the only reason the committee found out about the issue was because of a letter sent to the committee chair by the inspector general. In addition, from what is public about the communications between Schiff and Maguire, it seems that the agency head is not calling the shots here—as Clinton’s and Obama’s statements about the legislation seemed to envision—but, rather, some “higher power” outside of the agency is doing so. None of this looks good.

But in context, this incident looks even worse. In March, two senior administration officials told the Washington Post that the White House is “intent on challenging most, if not all, House Democrats’ document requests.” President Trump said in April that he intends to fight “all the subpoenas” issued by the House. The administration has refused to provide Trump’s tax returns to the House Ways and Means Committee even in the face of a statutory requirement (and the judge in that case decided not to expedite consideration of that case). And the president is aggressively litigating to protect his financial documents from being provided to Congress by various banks and his former accounting firm.

As I wrote earlier this year, the precise contours of any executive privilege are contested, and the executive branch, the courts and Congress tend to take divergent positions that favor their respective constitutional roles. The current situation before the House Intelligence Committee goes further—and not in a positive direction. Going forward, if the information the whistleblower provided to the inspector general implicates sensitive national security issues, the right path forward is for the executive branch to follow the framework of United States v. AT&T and seek “optimal accommodation through a realistic evaluation of the needs of the conflicting branches” in this situation.

If the information is being withheld based on a theory of some other type of executive privilege or for some other reason, the administration treads on considerably less solid legal ground. In the face of a statute that already self-limits the required reporting to instances of “particularly flagrant or serious” problems, the administration will need a very, very compelling reason that is rooted in the public’s interest—not the interests of a particular individual—to justify not providing the relevant information to the committee.

Practically speaking, however, the executive branch holds a lot of cards in this game—after all, it is in possession of the relevant materials. Litigation could take years, well beyond the 2020 presidential election. As the matter has been determined by the inspector general to be of “urgent concern,” years of litigation and delay is not merely the “mischief of polarization of disputes.” It may very well be a dereliction of constitutional duty.

-final.png?sfvrsn=b70826ae_3)