The Need for Clarity After Schrems II

The U.S. government has issued a white paper to help maintain the free and lawful flow of commercial and government data from the European Union to the United States after Schrems II.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On Sept. 28, the U.S. government issued a white paper (available on the U.S. Department of Commerce website) titled “Information on U.S. Privacy Safeguards Relevant to SCCs and Other EU Legal Bases for EU-U.S. Data Transfers After Schrems II.” This document provides detailed information about U.S. privacy standards governing foreign intelligence collection. We released it in order to help maintain the free and lawful flow of commercial and government data from the European Union to the United States.

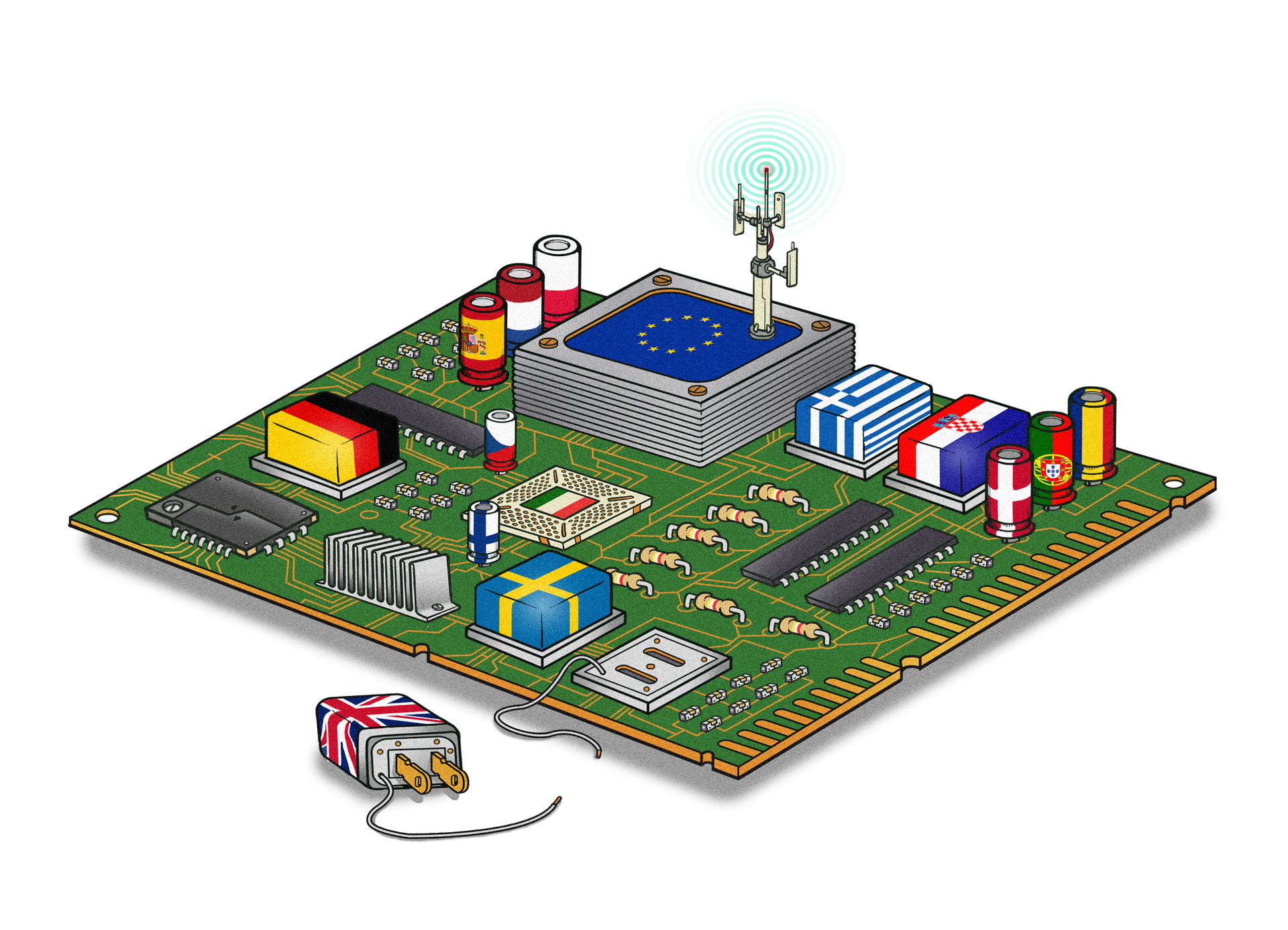

On July 16, the European Union Court of Justice (ECJ) handed down its judgment in Data Protection Commissioner v. Facebook Ireland and Maximillian Schrems, Case C-311/18. The case—better known as Schrems II—threw into disarray the future of the $7.1 trillion economic relationship between Europe and the United States, which, as Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross said, “is so vital to our respective citizens, companies, and governments.”

As an initial matter, the ECJ’s ruling invalidated the European Commission’s 2016 adequacy decision that underlays the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield Framework, on which more than 5,300 companies had come to rely for the transfers of personal data necessary to conduct transatlantic trade in compliance with EU data protection rules. What’s more, despite affirming an earlier European Commission decision that found standard contractual clauses (SCCs) to be an appropriate basis under EU law for transferring personal data to “third countries [that] do not ensure an adequate level of protection,” the ECJ’s ruling imposed new and unprecedented obligations on companies that use EU-approved data transfer mechanisms like SCCs and binding corporate rules (BCRs). In particular, companies relying on SCCs and BCRs now must verify, on a case-by-case basis, whether the recipient country offers a level of data protection equivalent to EU law with respect to government access to data. If the recipient country’s legal protections do not meet EU standards, then companies must provide appropriate safeguards, or refrain from transmitting the data. Few, if any, companies possess the legal expertise and resources to perform such evaluations with regard to either U.S. law or the laws of numerous other countries around the world.

In their efforts to comply with the Schrems II decision—and to make the pertinent assessments for transfers of personal data between the EU and the United States under SCCs and BCRs—numerous companies and individuals have contacted the U.S. government seeking additional information about privacy protections in U.S. law. The government’s white paper provides accurate and contextualized information about those protections. It also provides links to additional resources that may bear upon many companies’ analyses. While the white paper does not seek to provide companies with guidance about EU law, or about what position to take before European courts or regulators, it does represent a concrete, detailed, and good faith effort to conceptualize a possible path forward for restoring legal certainty around transatlantic data flows. Forging that path will require commitment and effort from both sides.

The need for constructive and good faith engagement between the EU and the United States on cross-border data issues has never been more urgent. More than two months after the ECJ’s decision, the operative rules remain decidedly unclear. While the U.S. government remains committed to negotiations with the European Commission on enhancing Privacy Shield to address the ECJ’s concerns in Schrems II, the ongoing uncertainty surrounding EU-U.S. data transfers puts companies and individuals on both sides of the Atlantic in an increasingly untenable position.

In 2015, the ECJ handed down the Schrems I decision, which invalidated Privacy Shield’s predecessor framework. Within 10 days of the ECJ’s decision, European authorities issued guidance announcing a pause on coordinated enforcement actions during EU-U.S. Privacy Shield negotiations and articulating a commitment “to ensure that all stakeholders are [kept] sufficiently informed” going forward. Yet more than 10 weeks after the Schrems II decision, European authorities have declined to afford any sort of enforcement “grace period” for the thousands of Privacy Shield participants—more than 70 percent of which are small- and medium-sized enterprises. And companies worldwide continue to await clear and uniform guidance on what measures they should adopt when using SCCs and BCRs—let alone any assurance that such guidance will be satisfactory in the view of the ECJ. Moreover, the European Commission has yet to provide a timeline for issuing its modernized SCCs or providing any details as to how such modernizations will address the ECJ’s concerns in Schrems II.

Meanwhile, relying on the Schrems II decision, the Irish Data Protection Commission (IDPC) already has reportedly shared a draft preliminary order that, if finalized, not only would halt all of Facebook’s transfers of personal data to the United States but also could potentially call into question the ability of any company to transfer EU personal data lawfully to the United States. This development implicates more than just Facebook. Hundreds of thousands of U.S. and EU businesses of every size and in every sector depend on digital services—and the data flows that power them—to operate and grow. Facebook has opposed the IDPC’s proposed order on procedural grounds, as the company appears to have received only three weeks to prepare a defense on a matter of existential importance; and the Irish High Court recently granted Facebook a stay on enforcement of the preliminary order. The company’s executives have made clear that they “have absolutely no desire, no wish, no plans to withdraw [Facebook’s] services from Europe”—but if the IDPC’s order is ultimately enforced, Facebook and other firms confronting similar difficulties may no longer be able to provide services in the EU.

In view of this potentially severe and rapidly accelerating threat to transatlantic commerce across a wide range of businesses, it is no surprise that leading European industry groups—including, among others, DIGITALEUROPE and a broad coalition of German industry associations—have begun sounding dire warnings. These groups have noted that the “[m]illions of transactions taking data in and out of Europe” every day “are the lifeblood of the modern economy”; emphasized that Schrems II has imposed case-by-case (and country-by-country) diligence obligations on small European businesses that will “most likely be an impossible task” for them to meet, especially when “trying to navigate the worst recession in living memory”; called for “[t]he EU Commission and data protection supervisory authorities ... to promptly publish uniform information on the level of data protection in third countries so that not every authority and every company has to carry out the check itself”; and, in the context of EU-U.S. transfers, sought “sanctions [to] be suspended until legal clarity has been created.”

The ongoing uncertainty created by the Schrems II decision, coupled with growing calls from prominent EU officials for data localization and European “digital sovereignty,” risks a wholesale breakdown of data transfers between the EU and the United States. Complicating the situation, the ECJ’s judgment represents more than a mere problem of transnational conflict of law. It requires scrutiny of non-EU countries’ laws and practices pertaining to government access, under ill-defined EU data protection standards—against a background where those very standards have not been applied to similar laws and practices of EU Member States. This uncertain and imbalanced status quo cannot hold. It requires a durable political solution.

The U.S. government is actively considering its options in light of the Schrems II decision and hopes to find a mutually constructive and productive path forward. The reality is that the EU-U.S. relationship is richly complex, and cross-border data issues impact virtually every aspect of that deep partnership.

As it should be clear by now, Schrems II does not implicate only commercial data transfers in the tech and digital sectors. To the contrary, the decision has potential implications on transatlantic information-sharing in areas like the health sector, including in ongoing medical research and clinical trials regarding treatments and vaccines for COVID-19; in law enforcement and intelligence cooperation, as the EU and U.S. face ever-dangerous threats to public safety and national security; and in EU financial institutions’ participation in U.S. financial markets, as both societies collectively confront unprecedented economic challenges. Schrems II also raises questions about data transfers from the EU to other rights-respecting nations all across the world—not to mention questions about data transfers to authoritarian nations, which merit far greater scrutiny than they have received to date. And it raises a number of issues concerning the many forms of information-sharing between, within and among EU Member States, and how those differences in treatment (as compared to treatment of transfers to the United States) can be justified.

Despite our differing legal approaches, the United States and the EU and its member states embrace common values with respect to individual privacy and data protection. As like-minded democracies committed to the rule of law, the EU and the U.S. have managed to develop policy solutions to bridge our legal systems before. Now more than ever, our mutual respect for privacy and data protection; our obligations to protect and improve the lives of our citizens; and our collective advancement in science and industry require both sides to make real, good-faith efforts to bridge our respective data protection regimes once again—and to provide the legal clarity and certainty essential to transatlantic commerce and cooperation.

-(1)-(1).png?sfvrsn=1bc11cd_4)

_-_flickr_-_the_central_intelligence_agency_(2).jpeg?sfvrsn=c1fa09a8_5)