A Not-So-Imperial Presidency

Despite critiques that the president exercises unilateral authority over use-of-force decisions, Congress appears to maintain consistent influence.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Since at least 1973, scholars of war powers have bemoaned an “imperial presidency” that is ready, willing, and able to utilize military force regardless of Congress’s wishes. Every cruise missile strike undertaken, every drone strike conducted, and every military operation ordered unilaterally by the president is argued by critics on both the right and the left to be further evidence of an unconstrained executive. Moreover, even on the rare occasions that presidents have sought formal authorization for the use of military force, critics still see evidence of presidential imperialism. For example, Lyndon Johnson maintained he did not legally require the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in the Vietnam War, and Office of Legal Counsel opinions from the George W. Bush administration make it clear that invading Iraq was considered within the president’s Article II powers. Perhaps most infamously, while George H.W. Bush ended up securing formal authorization from lawmakers shortly prior to launching Operation Desert Storm in 1991, he publicly maintained that he did not “have to get permission from some old goat in Congress to kick Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait.”

It is a fair characterization to say that the dominant understanding of the de facto state of the war powers today (and for the past half-century) is that, whatever the normative arguments over who should hold the chains to the dogs of war, Congress has little actual influence over use-of-force decisions. Since the beginning of the Cold War, U.S. presidents have possessed a massive standing military awaiting their simple command to take action. Courts virtually never step in to adjudicate war powers cases, and Congress itself has strong incentives to dodge responsibility for use-of-force decisions. The presidency, for its own part, has massive first-mover advantages, strong pressures to accrue more and more power over time, and—even in the unlikely event that legal barriers to the use of force are enacted—an ability to avoid constraints via creative legal theories. Thus, scholars of war powers nearly uniformly conclude that “Congress plays at best a small role in crisis policy.”

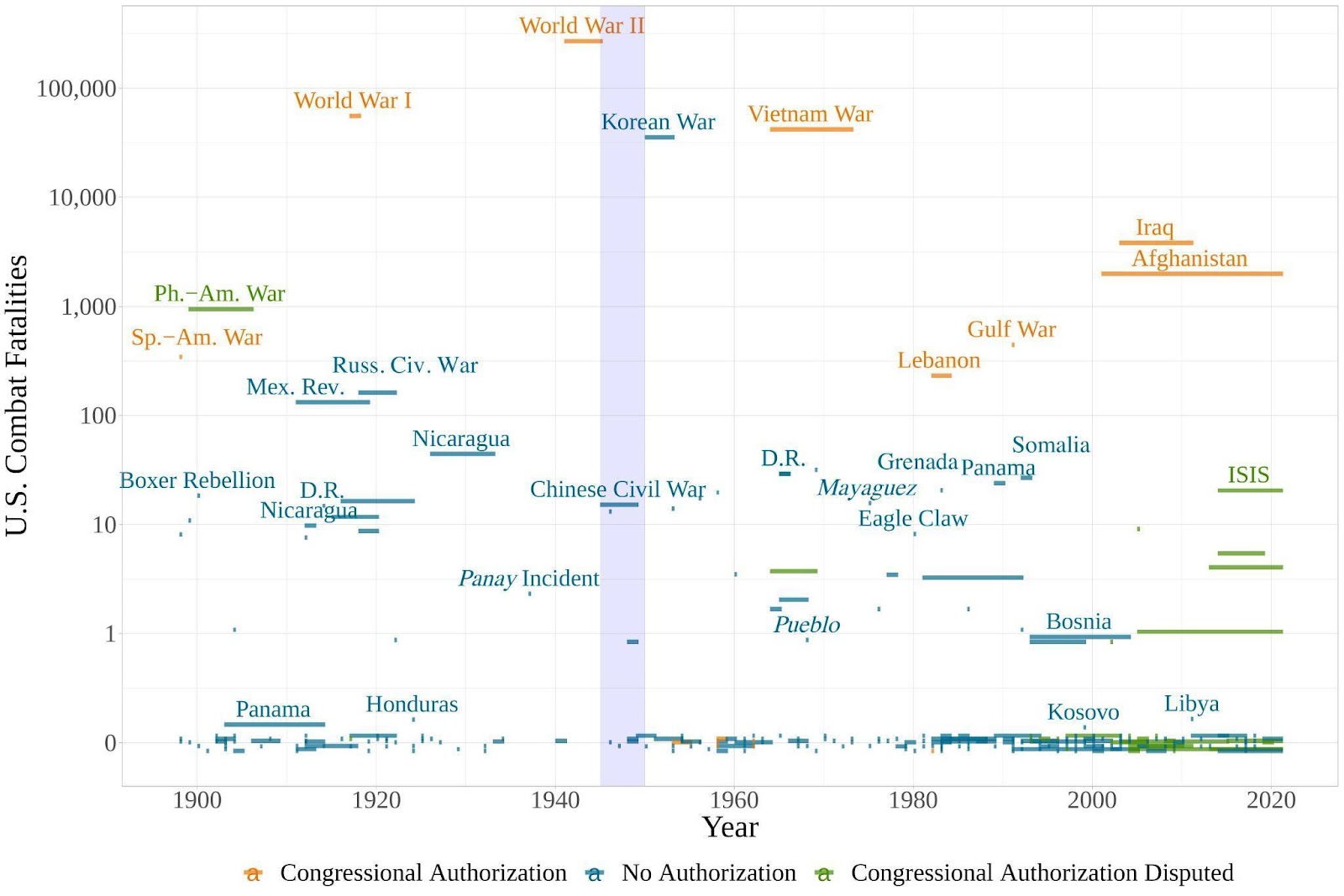

Such an interpretation, however, is hard to square with evidence suggesting significant congressional restraint on the executive. For example: As I pointed out previously on Lawfare (and as others have noted), while smaller uses of force are almost always undertaken unilaterally, the largest uses of force since the Korean War have uniformly been undertaken pursuant to formal authorization from Congress. This is shown in the chart below, which I created, along with the other charts in this article. (The data for all the charts comes from research I conducted with a large group of research assistants at the University of California, San Diego.) Note that unilateral uses of force undertaken after 1953 have all been several orders of magnitude smaller in scale than the war in Korea. Moreover, as I illustrate below, with a novel dataset measuring the sentiment of lawmakers in more than 100,000 floor speeches over the past 80 years, even smaller uses of force undertaken unilaterally are seemingly constrained by informal congressional sentiment. There are many instances of presidents avoiding a use of force—or being deterred—because of a lack of formal authorization or otherwise expressed congressional opposition to the use of military force.

Adversaries, furthermore, often have less faith in the imperial presidency than American scholars do. Opponents of the United States, instead, regularly base their expectations of American actions on sentiment they see in Congress. The Vietnam War, for example, is frequently cited as perhaps the apex of an unconstrained executive, but at the same time it is well recognized that Hanoi’s entire strategy—a strategy that worked, it should be noted—was based on a belief that the president was substantially constrained by Congress. Other adversaries, as well, have expressed their doubts over a president’s willingness to follow through with a threat when Congress seemed unsupportive of the endeavor. Saddam Hussein, for example, expressed his doubts that, in the fall of 1990, President Bush was willing to start a major war absent formal congressional authorization. At one point, Saddam said to his foreign minister, “[Congress is] going to stand there and tell [the president] they are not going to take responsibility and that he would have to do it and bear full responsibility on his own. Would he be able to do that?”

A Presidency Constrained

Critics bemoaning an imperial presidency often point to the many uses of force undertaken unilaterally by the president. Such an analysis simply asks (a) whether force was used (that is, anylevel of force) and (b) whether it was formally authorized by Congress.

As many scholars recognize, the vast majority of uses of force are not formally approved by lawmakers. The conclusion often drawn from this is that Congress has little influence over decisions to use military force and that presidents are willing and able to simply do whatever they see fit regarding military decisions. Buying into this conclusion, however, would be a mistake.

The problem with this analysis is that using military force is not a simple binary decision (use versus nonuse). There is, of course, a wide spectrum of military actions possible, ranging from an isolated drone strike to a world war. Similarly, congressional support for, or opposition to, the use of military force exists on a spectrum. Instead of asking the binary question of whether a president has secured formal authorization from Congress before utilizing military force, one should recognize that members of Congress can take actions short of legally binding legislation to express their sentiment toward a use of force. For example, members of Congress on both sides of the aisle widely supported the counter-ISIS campaign begun under the Obama administration in 2014. Yet, legislators refused to formally authorize the operation even when requested by the administration. A lack of formal authorization, hence, does not automatically imply a lack of informal congressional support for the use of force. It strains credulity to count the ISIS episode as evidence of an unconstrained executive, when President Obama was doing precisely what members of Congress were vocally demanding of him.

Thus, in order to determine how constrained a president is by Congress, a more nuanced analysis needs to be undertaken that addresses (a) what scaleof force was used (distinguishing between drone strikes on one end of the spectrum and full-scale wars on the other) and (b) what congressional sentiment was at the time (with uniform opposition existing at one end of the scale and uniform support—and, possibly, formal authorization—existing on the other).

Currently, it seems that the scale of force that presidents are willing to utilize is limited by the level of support that exists for military intervention in the legislature. On the one hand, an executive might be willing to conduct a targeted drone strike (in which little risk of escalation or American casualties is expected) regardless of Congress’s own preferences. On the other hand, presidents likely will undertake full-scale war only when they have secured formal authorization for the use of military force. In the middle, the White House will be willing to undertake military operations short of full-scale war unilaterally, but only when there exists informal congressional support for the operation.

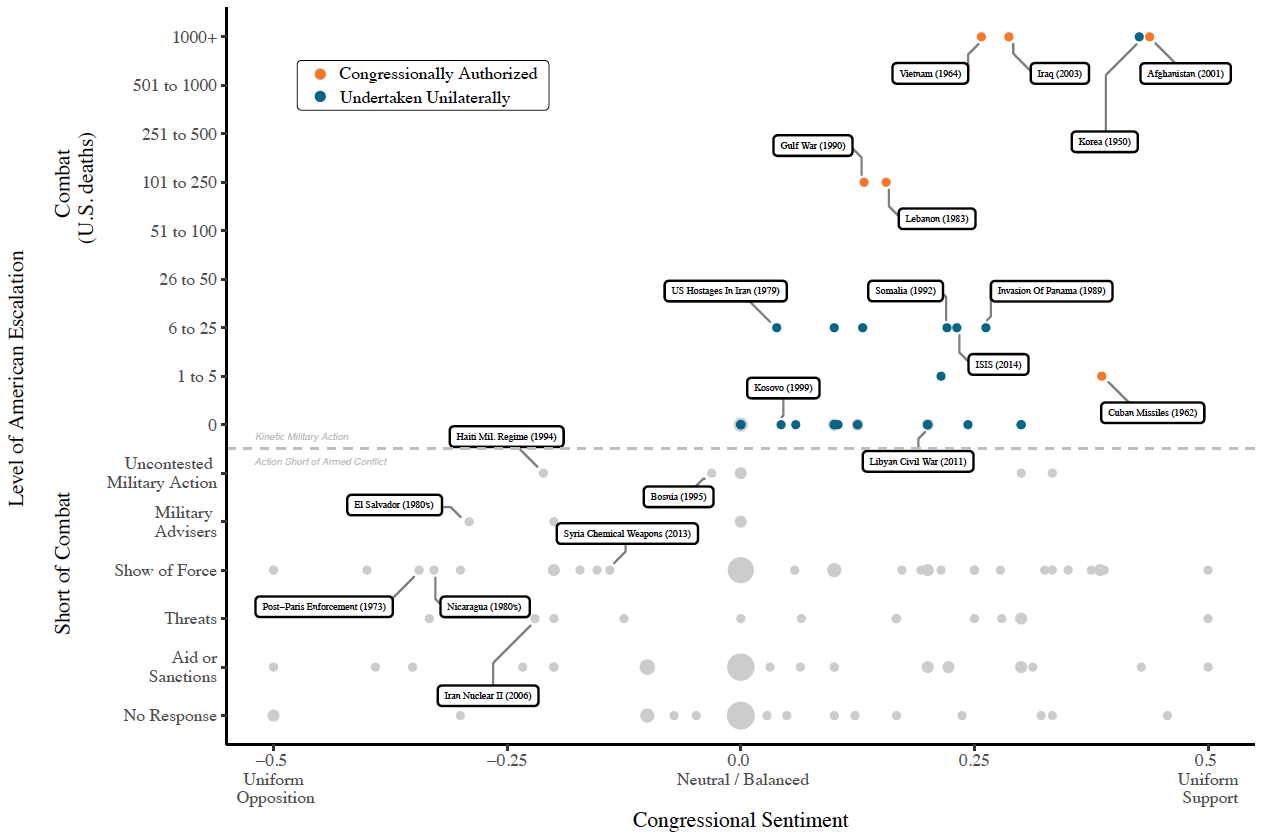

Plotted below are nearly 200 crises from 1946 to 2022 that involved the United States. The chart utilizes a novel dataset measuring congressional support for the use of force in specific crises via the rhetoric of lawmakers. This new dataset was created utilizing both hand-coding by humans and artificial intelligence to analyze the contents of over 100,000 congressional speeches during the time period.

The x-axis depicts this measure of informal congressional sentiment toward the use of American military force in the crisis. It is well recognized that members of Congress often have expressed preferences over the potential use of military force in a given crisis even when no actual vote—legally binding or otherwise—is undertaken. Members of Congress, for example, have expressed their preferred policy positions via press releases, tweets, cable news appearances, op-eds, speeches, and other media. Here, informal congressional sentiment is depicted as a “congressional support score” between -0.5 and +0.5 (corresponding to zero and 100 percent support for the use of force, respectively). This score is calculated by identifying the number of floor speeches made in Congress supporting the use of force, divided by the number of all relevant speeches (both in favor of, and in opposition to, the use of force). Positive scores—those further to the right—represent aggregate support in Congress for the use of U.S. military force, while negative scores—those further to the left—illustrate crises in which Congress expressed net opposition to the use of force. Note that for those crises in which U.S. military force was used, the speech data utilized ends once the U.S. intervention begins. Thus, congressional sentiment is measured beforeintervention occurs.

The y-axis utilizes an escalation ladder similar to others found in many political science datasets. The dotted horizontal line represents the point at which the U.S. enters combat. Thus, escalation levels above this line simply count the number of American combat fatalities suffered. This ranges from zero (engagements in which U.S. forces engaged in combat but which resulted in no American fatalities) to over 1,000 (full-scale war). Short of combat, we see crisis escalation short of actual kinetic action by U.S. forces. On the very low end exist crises in which the U.S. undertook no meaningful military or economic response. Above that are crises in which the U.S. utilized aid or sanctions but avoided a military action. Above this exist crises in which the U.S. made threats, undertook shows of force, or even deployed military advisers outside of combat.

An immediate pattern is seen from the plot: There are virtually no observations in the upper-left quadrant, an area that represents uses of military force that were opposed by Congress in the aggregate. In fact, the shape of this plot is completely consistent with what social scientists would call a continuous necessary condition or a constraint causal mechanism. Essentially, this plot suggests that congressional sentiment is closely constraining the scale of force presidents are willing to utilize. Or, if Congress says, “Don’t do it!,” the White House doesn’t do it.

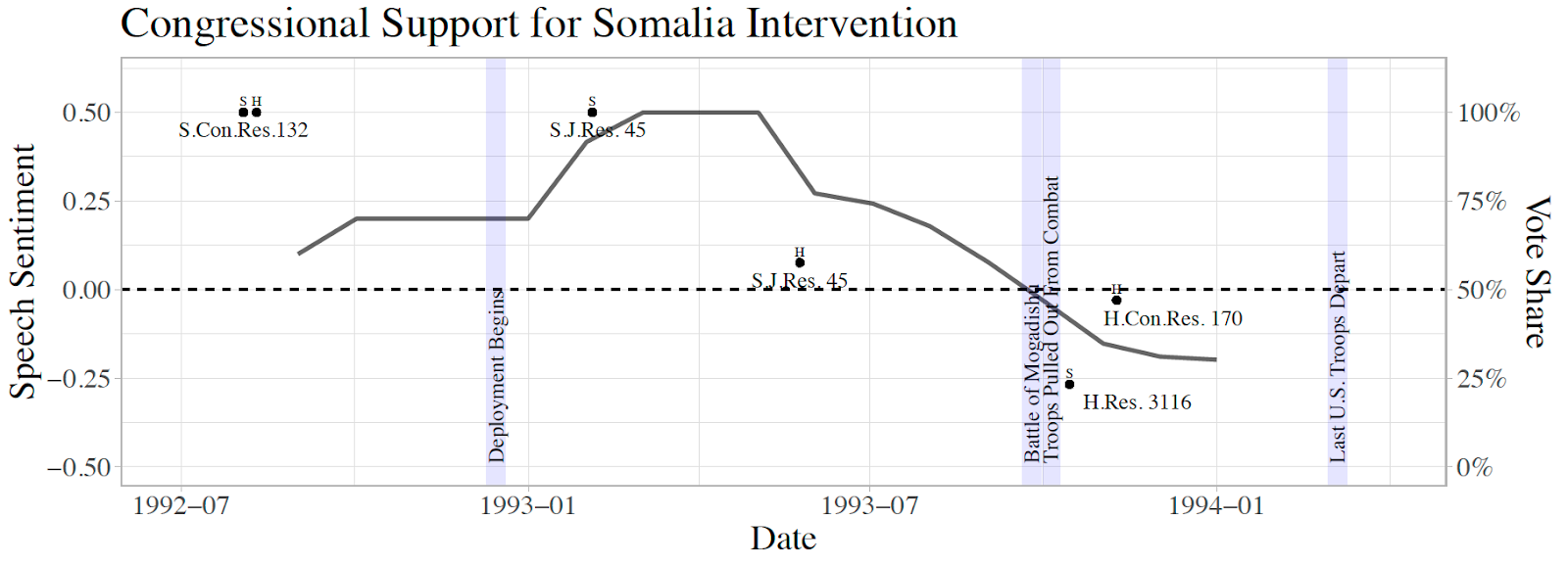

While—as is well recognized—there are many unilateral uses of force (shown in blue), almost all of these appear to have been informally supported by Congress ex ante. Consider examples such as the 1989 invasion of Panama, U.S. operations in Somalia in the early 1990s, or the 2011 Libya intervention. In each case, the president employed substantial military force (though well short of full-scale war) without securing formal authorization from Congress ex ante. Nevertheless, it would be a substantial mischaracterization to say the White House contradicted the will of the legislature in these crises. To the contrary, Presidents Bush, Clinton, and Obama seemingly fulfilled the wishes of Congress as expressed through its informal sentiment. In Panama, for example, senators on both sides of the aisle heavily pressured a reluctant Bush to intervene—and he did so only after an American Marine was murdered and Panama declared war on the U.S. In Somalia, the original deployment of troops was well supported in Congress, as evidenced by both roll call votes (S. Con. Res. 132and S.J. Res. 45—noted in the chart below) and sentiment derived from floor speech data. Once sentiment shifted to opposition—especially after the infamous Battle of Mogadishu in October 1993—the administration was forced to quickly pull U.S. forces out of combat and then out of the country.

In Libya, as well, President Obama intervened absent formal approval from Congress but, nonetheless, under the cover of substantial congressional support at the beginning of the operation. The Senate, for example, unanimously passed S. Res. 85 calling for “the [U.N.] Security Council to take … action … to protect civilians in Libya from attack, including the possible imposition of a no-fly zone over Libyan territory.”As the conflict dragged on, congressional support waned considerably, but so did the level of U.S. involvement.

To be sure, there are some substantial uses of the military that occurred in the face of congressional opposition. Two clear examples are the 1994 Haiti intervention (clearly opposed by a majority in Congress) and the dispatch of 20,000 peacekeepers to Bosnia at the end of 1995. Notice what was not happening in these examples, however: The U.S. was not engaged in combat. In the case of Bosnia, for example, the absence of combat was a clear sine qua non of the deployment—Richard Holbrooke recalls emphasizing that “[t]here is no peace without American involvement, but to repeat, there’s no American involvement without peace.”

There are, however, quite a few examples of congressional opposition deterring presidents from intervening when they otherwise would have liked to. The imperial presidency thesis suggests cases like these would not exist, but they do. Consider, for example, the following:

- Dien Bien Phu (1954): The Eisenhower administration sought to intervene to assist besieged French forces, but Congress refused to authorize the use of force, deterring Eisenhower.

- Second Taiwan Strait Crisis (1958): U.S. military leaders and an ally (the Republic of China) sought for the U.S. to clearly declare it would defend the so-called offshore islands of Kimmen and Matsu, but pressure from Congress prevented this.

- Six-Day War (1967): President Johnson sought to intervene but refused to do so absent congressional authorization, which was not forthcoming given “Tonkinitis” (exhaustion due to the Vietnam War) in Congress.

- EC-121 Incident (1969): President Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger sought to respond militarily against North Korea after it shot down an American plane in international airspace and killed 31 Americans. They were, however, ultimately deterred by congressional opposition.

- Post-Paris Vietnam (1973): Immediate encroachments by North Vietnam were seen as tests of American willingness to uphold the Paris Peace Accords that Nixon and Kissinger worked so hard to conclude in January 1973. The administration assessed that a mere week of bombing of North Vietnamese forces would bring Hanoi back in compliance, but the White House was unwilling to do so due to extreme opposition in Congress.

- Fall of Saigon (1975): President Ford came into office promising to uphold the assurances of Nixon to prevent a North Vietnamese attack on Saigon, but the Case-Church Amendment (banning the use of military force in Southeast Asia) prevented him from doing so. Indeed, even on the question of evacuating South Vietnamese citizens who were especially susceptible to persecution by the advancing communist forces, the administration was able to remove only around five percent of those it considered at-risk.

- Nicaragua (1980s): The Reagan administration spent eight years attempting to influence events in Central America—being so resolved in this course as to violate federal law and embroil itself in the Iran-Contra scandal. Nonetheless, the administration avoided the use of military force because of adverse reactions expected in Congress.

- Rwandan Genocide (1994): Despite having a strong interest in protecting human rights, the Clinton administration was deterred from intervening in Rwanda due to resistance from Congress after the disaster in Somalia the previous year.

- Iran (2007): A nascent nuclear weapons program, support for terrorism, and direct support for insurgents killing U.S. soldiers in Iraq provided a push to confront Iran in the mid-2000s within the Bush White House. While the administration planned for attacks against Iran and began making its case to the public, resistance from Congress—especially from then-Sen. Joe Biden—eventually deterred this.

- Syria (2013): After setting a “red line” against the use of chemical weapons in Syria, President Obama approved plans for a retaliatory strike against the Assad regime after a sarin gas attack in Ghouta in August 2013. Shortly before the attack was to commence, however, Obama suddenly announced he would request formal authorization from Congress. Some observers have suggested that Obama went to Congress knowing he would be rejected, but no personal recollection of the events from those involved in the decision-making supports this interpretation. Instead, these recollections show that Obama was worried that opportunistic members of Congress would attack him later on if he acted unilaterally and the mission proceeded poorly.

Thus, there are many examples of presidents being deterred from intervening in a crisis due to congressional opposition, regardless of the widespread belief in an imperial presidency.

It is well recognized that the president, de facto, is not substantially legally constrained in the use of military force. The data suggests that presidents are, however, de facto closely politically constrained by Congress. While presidents have a nearly unassailable ability to utilize military force unilaterally, acting in the face of congressional resistance dramatically increases the political fallout they can expect if the use of force ends poorly. Fear of having sole responsibility for a war gone bad deters presidents from the use of force when a sufficient level of support in the legislature is lacking. This political reality has an unintended consequence: the scale of force that presidents are willing to utilize is closely constrained by sentiment in Congress toward the use of force. As legal scholars Henry B. Cox and Abraham D. Sofaer recognized 40 years ago, “In the final analysis, politics, rather than law, rules in the struggle between president and Congress.” These political constraints appear quite strong, indeed.