Nuclear Brinkmanship: U.S. Sanctions Against Iran Explained

Negotiations between the U.S. and Iran over the mutual return of the two countries to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action are currently deadlocked. This post provides an overview of U.S. sanctions against Iran and explains those sanctions currently at issue in stalled talks.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

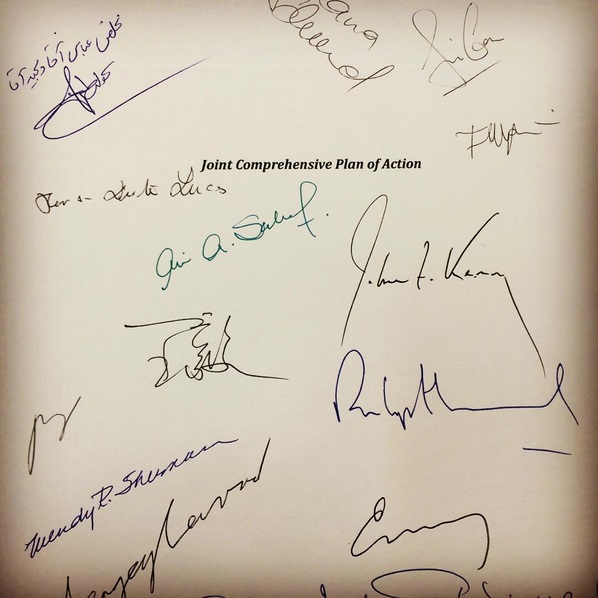

Negotiations between the United States and Iran are reportedly at a stalemate over final terms of an agreement for the mutual return of the two countries to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The talks first began in early 2021 between the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Russia, China and Iran. While they have reportedly resulted in a draft agreement, the recent impasse has made the future of any agreement more tenuous.

The current halt is the result of two reported Iranian demands: first, that the United States withdraw the designation of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO); and second, that the Biden administration guarantee that a future U.S. administration will not withdraw from the agreement. The Biden administration has yet to agree to the first condition (and signaled that it may not agree to do so as a part of the JCPOA), and the second would face domestic political and constitutional constraints, as Curtis Bradley and Jack Goldsmith explained previously on Lawfare.

This post is intended to help explain the legal background behind the FTO designation in the context of the U.S. sanctions regime and to highlight other possible obstacles—namely, the potential for Congress to limit the president’s ability to waive sanctions against Iran—that may arise if a new agreement is reached.

Background on U.S. Sanctions Against Iran

The U.S. sanctions regime against Iran is predicated on a mosaic of multilayered authorities that include statutes, executive orders and regulations. Existing legislation that grants the president the authority to sanction Iranian entities likewise grants the administration the authority to unilaterally amend, waive or terminate such sanctions in the future.

The U.S. has imposed two forms of sanctions on Iran since the Islamic regime first came to power in 1979: primary and secondary sanctions. U.S. primary sanctions against Iran are those that directly prohibit U.S. citizens and entities (and those with a presence in the United States, such as corporations and financial institutions) from engaging in specified activities with counterparts inside Iran. Primary sanctions rely on a “U.S. nexus” as the basis for asserting jurisdiction over parties and have remained in effect continuously since 1979. Succeeding administrations have expanded the scope of these sanctions throughout the years.

Unlike primary sanctions, secondary sanctions are operative against non-U.S. parties’ transactions with sanctioned Iranian entities regardless of a U.S. nexus. That is, the sanctions are against non-U.S., non-Iranian entities specifically and solely because they are engaging in transactions with designated Iranian entities. These sanctions seek to deter the behavior of these foreign entities even if the underlying transactions don’t have direct ties to the United States and regardless of whether the action is legal in the home jurisdiction. They do so by threatening to cut off the foreign person or entity from access to the U.S. financial system (such as U.S. banks and currency). Secondary sanctions are considered controversial under international law, in part, because they are viewed as an extraterritorial assertion of U.S. sovereign power over parties and dealings wholly unrelated to the United States.

U.S. administrations have had little difficulty sourcing their authorities to impose economic sanctions on Iran. The Obama administration embarked on a multilateral effort to impose economic costs on Iran for its nuclear and other activities. Obama’s efforts focused on expanding sanctions under existing authorities both specific to Iran, like the Iran Sanctions Act of 1996 (ISA) (which was the first set of secondary sanctions imposed on Iran), as well as more recent legislation such as the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA), the Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act of 2012 (ITRSHR), and the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act of 2012 (IFCA).

These sanctions, working in conjunction with broad-based authorities under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) and the National Emergencies Act (NEA), were used by the Obama administration to expand the scale and scope of financial pressure on Iran to bring it to the negotiating table. In January 2016, Obama issued Executive Order 13716 relying on his statutory authority under IEEPA, NEA, ISA, CISADA, ITRSHR and the IFCA to suspend the application of specific secondary sanctions against Iran. The JCPOA did not alter or otherwise change primary sanctions against Iran.

Subsequently, Congress extended ISA (due to expire at the end of 2016) for another 10 years and passed the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) in 2017 to authorize then-President Trump to sanction Iran’s ballistic missile program and other activities. Two years later, President Trump reimposed the secondary sanctions suspended by the Obama administration and expanded the scale and scope of many of these sanctions programs as a part of a “maximum pressure” campaign. Lawfare has previously detailed the impact of Trump’s maximum pressure campaign. Trump-era sanctions were allegedly tied to Iran’s non-nuclear-related activities in an effort to insulate the designations from rollback by a future administration. The following provides an overview of sanctions reimposed by Trump:

- Executive Order 13846 (Aug. 6, 2018) Withdrew from the JCPOA and reimposed all sanctions previously waived under the agreement, including blocking Iran’s purchase of U.S. bank notes; prohibiting transactions with the National Iranian Oil Company and the Central Bank of Iran; restricting transactions with Iran’s energy, shipping, shipbuilding and port sectors; authorizing sanctions on foreign financial institutions financing Iran’s auto sector, petroleum market, petrochemicals and other trade; prohibiting U.S. Export-Import Bank activities; and restricting access to the U.S. financial system.

- Executive Order 13871 (May 8, 2019) Blocked assets and transactions related to trade in Iran’s iron, steel, aluminum or copper sectors.

- Executive Order 13876 (June 24, 2019) Blocked assets and transactions with the Supreme Leader of Iran, his office or any person affiliated with the office.

- Executive Order 13902 (Jan. 10, 2020) Blocked assets and transactions with those designated as operating in Iran’s construction, mining, manufacturing, or textiles sectors or any “other sector of the Iranian economy as may be determined by the Secretary of State.”

- Executive Order 13949 (Sept. 20, 2020) Imposed an arms embargo on Iran that prohibited any activity that materially contributed to the supply, sale, or transfer to or from Iran of any arms or related materiel, including spare parts. This order was intended to counter the scheduled October 2020 lifting of the U.N. arms embargo against Iran as a part of the JCPOA.

In 2018, as a response to the Trump administration’s reimposition of secondary sanctions against Iran, the E.U. passed a “blocking” statute in an attempt to blunt the impact of the sanctions’ extraterritorial effect on domestic companies. The blocking statute prohibited compliance by E.U. parties with prohibitions or requirements demanded by foreign laws. E.U. officials were explicit in noting that they saw U.S. attempts to regulate the activities of non-U.S. persons outside of U.S. territorial jurisdiction to be a violation of international law and did not recognize such extraterritorial effects. In turn, the blocking statute operated by nullifying the effect of any foreign court ruling based on foreign laws that adversely impacted E.U. entities and by allowing E.U. entities to recover damages in court for money lost as a result of specified foreign laws.

While it remains unclear whether the blocking statute has any teeth, a December 2021 European Court of Justice (CJEU) ruling in Bank Melli Iran v. Telekom Deutschland GmbH could provide Iran with a newfound ability to bring civil suits to recover lost proceeds over canceled contracts in response to the reimposition of U.S. sanctions in 2018. The CJEU held in that case that it was possible for a non-E.U. entity to invoke the blocking statute to bring civil suit against an E.U. company for cancellation of a contract.The court found that the burden of proof would be on the defendant, the E.U. company, to demonstrate that its reasons for terminating a business transaction with Iran was not the result of U.S. sanctions. While the blocking statute was designed to preserve the freedom of contract for European companies, this ruling suggests that it may have newfound implications for U.S. attempts to pressure Iran via secondary sanctions.

IRGC’s FTO Designation

In 2019, the Trump administration, as a part of its maximum pressure campaign against Iran, designated the IRGC as an FTO. This marked the first instance in which the United States designated a foreign state’s military as a terrorist organization using the State Department’s authority under Section 219 of the Immigration and Nationality Act. As Elena Chachko detailed previously for Lawfare, the IRGC and the IRGC Qods Force—a paramilitary arm of the organization responsible for attacks against U.S. and allied forces abroad—were already the subject of numerous U.S. sanctions for their terrorism-related activities, ballistic missile production and human rights abuses. As a result, the Trump administration’s designation was largely symbolic and added little new economic pressure on the Iranian regime. Still, the designation has posed a significant obstacle in current talks and it is worthwhile to explain the difference between it and the other largely overlapping terrorism-related designations of the IRGC.

The United States first named Iran as a state sponsor of terrorism in 1984 pursuant to the Export Administration Act of 1979 after determining that the country provided repeated support for acts of international terrorism. To remove Iran from the state sponsor of terrorism list—absent regime change in Iran—the president would have to certify to Congress that Iran has not supported international terrorism in the preceding six months and has provided assurances that it will not do so in the future. Congress then has the opportunity to block the removal by enacting a joint resolution rejecting the certification, although such a resolution would be vulnerable to presidential veto.

In addition to this designation, the United States has sanctioned the IRGC for its nuclear and ballistic missile work as well as its human rights abuses. In 2017, the United States sanctioned the IRGC for its support for international terrorism under CAATSA. In that statute, Congress mandated that the president use existing IEEPA and Executive Order 13224 authorities to designate the IRGC as a specially designated global terrorist organization. As background, Executive Order 13224 was enacted by the Bush administration shortly after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. The order mandated the freezing of U.S.-based assets of, and a ban on transactions with, any entities determined by the administration to be supporting international terrorism. The IRGC Qods Force has been designated under that order since 2007.

In contrast, Trump’s FTO designation operates by subjecting any U.S. person or person under U.S. jurisdiction who “knowingly provides material support or resources to an FTO” to fines or up to 20 years in prison. Given that Iran’s IRGC comprises approximately 640,000 individuals and is a part of Iran’s normal military, such designations expand the breadth and reach of the U.S.’s ability to prosecute civilians with ties to the IRGC. The FTO designation can include a broad spectrum that includes family members of IRGC-affiliated individuals and foreign countries that receive delegations composed of current or former IRGC officials. To address some of these concerns, the U.S. explicitly provided a carve-out for regular diplomatic or humanitarian assistance to the IRGC.

Domestic Obstacles Ahead for Sanctions Removal

If a new deal is reached with Iran, President Biden may face stiff opposition from Congress. First, Congress has already signaled that it will want to review a new nuclear agreement with Iran. The Biden administration, like the Obama administration, may have to submit any new nuclear agreement with Iran to Congress so that it can weigh in on the agreement. In May 2015, Congress passed the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015 (INARA) as an amendment to the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 (AEA). INARA required that the executive branch submit any agreement with Iran to Congress for a review period during which time Congress would have the opportunity to disapprove of the accord. The Biden administration had initially hinted in February that it might not submit a new agreement to Congress, arguing that the JCPOA was already subject to congressional review in 2015. However, changes to the scope of nuclear activities that Iran may be permitted to perform or to the timeline of the original agreement, among other terms, may be grounds for Congress to press successfully for resubmission.

Second, two separate bills introduced by Republican members of Congress can significantly curtail the Biden administration’s ability to deliver sanctions relief to Iran as a part of a renewed JCPOA. Sen. Bill Hagerty in February 2021 introduced the Iran Sanctions Relief Review Act of 2021, which would require that Congress have the opportunity to review (and reject) actions to terminate or waive sanctions imposed against Iran. This bill requires that the president notify Congress of his intention to remove sanctions on Iran and, if so, provide Congress with a 30-day window to disapprove of such action. This limit would still be subject to the president’s veto.

Separately, Sen. Marco Rubio introduced legislation in March to prohibit the Biden administration from waiving sanctions that are tied to limits on Iran’s civilian nuclear activities. Under the terms of the original JCPOA, Iran was permitted to partake in some civilian nuclear work in conjunction with international parties—mainly Russia and China—in exchange for limiting its program. If passed, this bill would likely undercut any agreement with Iran as it would prohibit U.S. sanctions waivers for a central concession from the U.S. in the agreement.

Finally, while the president retains a great deal of authority under existing sanctions laws to waive or suspend sanctions and can simply revoke Trump’s executive orders, his ability to undo some of Trump’s sanctions may be subject to additional political scrutiny. In particular, President Trump tied much of his reimposed sanctions to CISADA, which—unlike IEEPA and NEA—requires, pursuant to Section 401, that the president certify that Iran has ceased its involvement in international terrorism and weapons proliferations-related activities before terminating sanctions. While the president retains the authority—absent new laws—to waive or terminate such sanctions, it may be politically more costly to do so than previously.

Future of U.S. Sanctions on Iran

The strength of U.S. sanctions against Iran must be viewed in light of their cumulative impact over the past 40 years, whereby consistent sanctions have created little political incentive for countries to evade sanctions and minimized the role and impact of Iran’s economy on global economic stability.

The efficacy of U.S. sanctions is tied to the strength of the U.S. economy and financial system. Much of the power of U.S. secondary sanctions relies on the deterrence effect that they have on non-U.S. actors that comply because they are unwilling to risk getting cut off from U.S. financial institutions. The ever-present risk is that increasing use of U.S. sanctions on an array of bad actors simultaneously increases the likelihood that at least some foreign entities will find ways to do business outside of U.S. markets. In fact, the more actors that are subject to U.S. sanctions and isolated from Western economies, the more likely it is that a sustainable market of U.S. enemies can begin to trade together without fear of repercussion. The reality is that these economies are much weaker without the West, but the risk over the long term remains.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and resulting sanctions have further complicated this picture. Sanctions against Russia’s economy, which have yet to meaningfully restrict the trading behavior of China and India, may—over the long term—create a safe harbor for trade between sanctioned countries and major economic players around the world. Where the relative size of Iran’s economy may not have created much incentive for countries to ignore U.S. secondary sanctions, when Iran’s economy is combined with Russia’s, the two countries may be able to chip away at the impact of U.S. sanctions. Russia has already attempted (unsuccessfully) to assert a sanctions carve-out for trade with Iran via any renewed JCPOA agreement. Still, Russian and Iranian cooperation against U.S. sanctions is not a foregone conclusion, in part, because Russia’s own exclusion from international energy markets creates an opening for Iran to assert its relevance in alleviating pressure on oil and gas supplies.

While talks with Iran are at an impasse, the risk remains that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may have altered the leverage of parties in the talks. Over time, U.S. leverage against Iran may decline as global appetite for an alternative supply of oil and gas to replace Russian energy supplies becomes more desperate. This, when combined with the increasingly large number of countries and economies subject to U.S. secondary sanctions, may dull the impact of U.S. sanctions pressure against Iran and thereby limit the United States’ ability to ensure, via sanctions, that Iran’s malign activities do not threaten U.S. interests.