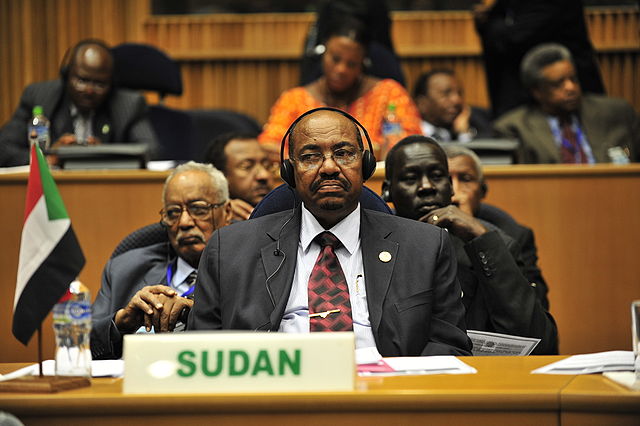

Omar al Bashir has left the Building (and the Country)

The international criminal law world was abuzz the last two days over the possibility that the President of Sudan, Omar al Bashir, might actually be arrested in South Africa on International Criminal Court (ICC) arrest warrants dating from 2009 and 2010, charging him with genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The international criminal law world was abuzz the last two days over the possibility that the President of Sudan, Omar al Bashir, might actually be arrested in South Africa on International Criminal Court (ICC) arrest warrants dating from 2009 and 2010, charging him with genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. Alas, Bashir slipped out of the country just moments before a South African judge ordered his arrest, leading to a chorus of condemnations of the South African government for its complicity in his escape.

Despite all the drama (and fair bit of breathless minute by minute commentary along the way), the outcome of this episode was never very much in doubt. The South African government had twice before discouraged Bashir from coming to the country because of the outstanding warrants, and so when it allowed him to come this time to attend an African Union summit, it had plainly already made the decision to ignore its obligation under the Rome Statute (of which South Africa is a party) to arrest Bashir. What it apparently did not anticipate is that an NGO, the South African Litigation Centre, would file an application with the court in South Africa to force the government to comply with the law. But having decided to allow Bashir to come to South Africa in the first place, it was hard to imagine that the government would then turn around and arrest him, and so away he went. The South African judge ruled that the government’s actions violated both the Constitution and the court’s order that Bashir remain in South Africa pending the litigation, and it ordered the government to file an explanation of actions with the court.

Some academics (here and here) have argued that in fact South Africa had no obligation to arrest Bashir because he continues to enjoy immunity from arrest as long as he remains President of Sudan. Countries that sign up to the Rome Statute agree to waive this form of personal immunity (See Article 27 of the Rome Statute), but the wrinkle here is that Sudan is not itself a member of the ICC and so never agreed to anything. The Court gained jurisdiction when the UN Security Council referred the case to the ICC in 2005 pursuant to its Chapter VII powers (UNSCR 1593). However, the better argument is that in making the referral, the Security Council put Sudan in the position of a State Party to the Rome Statute and therefore imposed a waiver of immunity (as it has the power to do). It is difficult to understand why the Security Council would refer the case to the ICC while allowing Sudan to shield officials from arrest through assertions of personal immunity, and when the UNSC has established ad-hoc tribunals it has always included a waiver of immunity. Further, there is no risk that concluding that Bashir has indeed been stripped of immunity under these very particular circumstances will undermine the broader immunity regime that is critical to diplomatic relations. Both the ICC and the South Africa court have rejected the claim that Bashir enjoys, as a sitting head of state, immunity from arrest (and Bashir’s flight from South Africa before the judge’s decision there suggests that neither he nor the government had much confidence in the argument either).

So what does this mean for the ICC? Some have described South Africa’s complicity in Bashir’s escape as another “blow” to a struggling ICC, while others have cogently argued that Bashir’s flight from South Africa (with no likelihood that he will return anytime soon) in fact demonstrates the nascent power of the Court and the rule of law (here and here).

Both perspectives underscore a critical fact about the ICC: it will only be as strong and successful as the international community decides, each and every day, to make it. The work of the international community did not end with the signing of the Rome Statute in 1998 and its coming into force in 2002. That was just the beginning. The drafters of the Statute created a Court with very limited independent power that is almost entirely dependent on ongoing state cooperation to succeed. Unsurprisingly, states that are the subject of ICC investigations (called “situation countries”) will often be less than excited about cooperating with the Court (unless the Court is principally targeting rebel forces in the country), and even states that are not targeted but could assist in investigations will sometimes find the pursuit of justice to be inconvenient. The ICC will only succeed when the situation country itself supports its intervention or when outside influential countries prioritize cooperation with the Court in all of its diplomatic and political interactions with the situation country.

What this means is that there will not be one ICC story of success or failure, but rather different stories in its various investigations depending on the level of cooperation and support the Court receives in each case. The ICC will experience both successes and failures for the foreseeable future, and it will not usually be possible to predict ex ante which way an investigation and prosecution will go. In the case of Sudan, the beginning was extremely promising as it started with a UNSC referral, which one might have thought reflected a strong commitment to the ICC and its work. But over time, the interest faltered. Bashir’s trip to South Africa was just the latest of several that he has made with impunity to States Parties of the ICC (specifically the DRC and Chad; see here for all places where Bashir has traveled and where he has been refused entry). And just last December, the ICC Prosecutor told the Security Council that she was forced to “hibernate” the Sudan cases because of the lack of support from the UN for her cases there.

What this also means is that to the extent there are “politics” in the work of the ICC, they exist principally at the level of the actions (and inactions) of the states rather than within the Court itself. In the recent Bashir episode, the Court followed a legal process: the Prosecutor investigated the crimes, filed an application for an arrest warrant with the judges who then issued warrants, which were then transmitted to South Africa to be acted upon pursuant to the legal obligations within the Rome Statute to which South Africa had signed up. It was South Africa, however, that chose politics over law, allowing Bashir to flee ignominiously while snubbing both the ICC and its own court. To be sure, there is a larger politics at work in the decisions about which countries have joined the ICC and which cases get referred to the ICC (Sudan and Libya were, but Syria has not been). The point is that the ICC itself can only play within the space that has been allotted to it. It will succeed when relevant states insist on its success.

***

Alex Whiting is a Professor of Practice at Harvard Law School, where he teaches, writes and consults on domestic and international criminal prosecution issues. From 2010 until 2013, he was in the Office of the Prosecutor at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague. He there served first as the Investigations Coordinator, overseeing all of the investigations in the office, and then as Prosecutions Coordinator, overseeing all of the office’s ongoing prosecutions.