On DOGE, Directives, and DOJ

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

“US DOGE service advises and consults,” said Kendall Lindemann, a DOGE representative, during a sworn deposition earlier this month.

Elon Musk “only has the ability to advise the President,” the Justice Department wrote in a court filing in February.

The United States DOGE Service “consults with agency heads and their designees on technology improvements and other matters related to the President’s DOGE agenda,” declared Amy Gleason, the purported administrator of DOGE.

For months, the Trump administration has fended off legal challenges to DOGE’s sweeping interventions in federal governance by insisting that neither DOGE nor its de facto leader, Elon Musk, have real decision-making authority. The common refrain—expressed in court filings, sworn statements, and depositions—is that DOGE merely advises agencies on which contracts to slash or which personnel to lay off en masse. According to the government, it’s ultimately up to the relevant agency officials to decide whether to act on DOGE’s recommendations.

It’s a convenient narrative. As a matter of legal strategy, the idea that DOGE merely advises rather than directs agency decision-making is a key part of the government’s defense in litigation alleging violations of the Appointments Clause. In other cases, the government has argued that DOGE is not an “agency” subject to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) because its role is limited to advising and assisting the president.

To be sure, there’s already a voluminous body of public evidence–from Trump and Musk’s own statements to court documents to media reporting on DOGE’s activities–contradicting the government’s claim that DOGE is an advisory entity. But much of that evidence, while compelling, is circumstantial or based on “social media posts and news reports,” as one appeals court recently complained.

All of which has enabled government officials and lawyers to make dubious claims about DOGE while maintaining a veneer, albeit a thin one, of plausible deniability.

But a new court filing reveals the most compelling evidence yet that the government has been spinning a fiction in federal court.

The underlying case, Amica Center for Immigrant Rights v. United States Department of Justice, was brought by a network of legal aid groups that subcontract with the Acacia Center for Justice, which provides legal services for non-citizens and unaccompanied minor children.

The legal aid groups first sued back in January, after the Justice Department issued a “stop work” order for the programs, citing Trump’s “Protecting the People Against Invasion” executive order. Shortly after the plaintiffs filed suit, the Justice Department rescinded the “stop work” order. Then, days later, Attorney General Pam Bondi issued a memorandum directing the Justice Department to review—and, potentially, terminate—all contracts with organizations “that support or provide services to removable or illegal aliens.” The legal aid groups moved to block the Justice Department from terminating its contracts based on Bondi’s memorandum.

On March 17, Judge Randolph Moss of the District Court for the District of Columbia held a hearing on the plaintiffs’ motion for an injunction. Judge Moss indicated that, because there was no pause or termination of the funding at that time, he was inclined to hold the motion under consideration pending any future action taken by the Justice Department. Later that day, the judge entered an order requiring the Justice Department to provide the plaintiffs “with at least three business days’ notice before suspending or terminating” any of the funding at issue.

All of which brings me to DOGE and the events that occurred at the Justice Department on April 3 and beyond. The excessively detailed account of those events presented below is based on administrative records, including internal Justice Department emails and documents, that were recently filed by the government in the Amica litigation. The new details contained therein, which have garnered little attention, suggest that DOGE directed senior Justice Department officials to terminate the Acacia Center’s contracts.

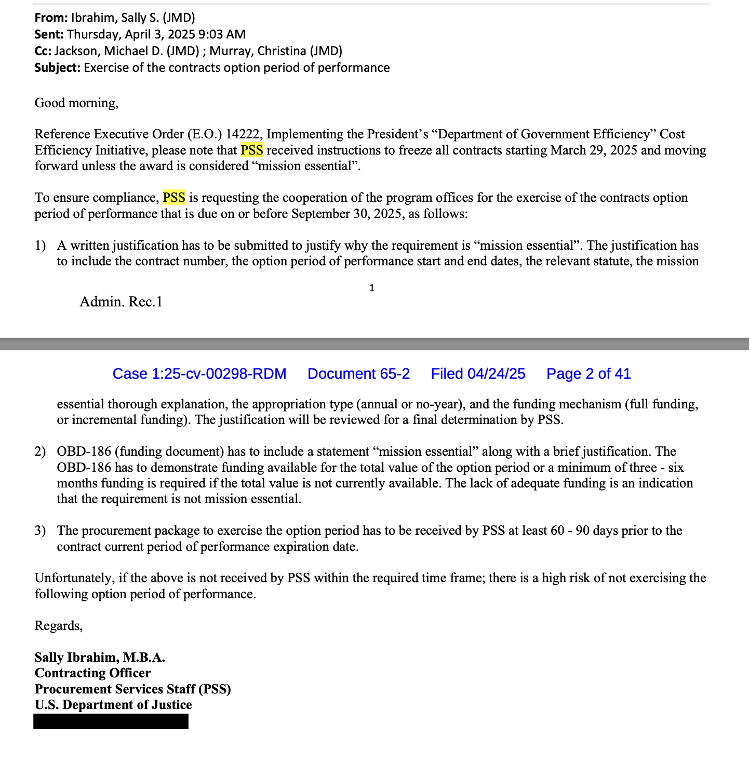

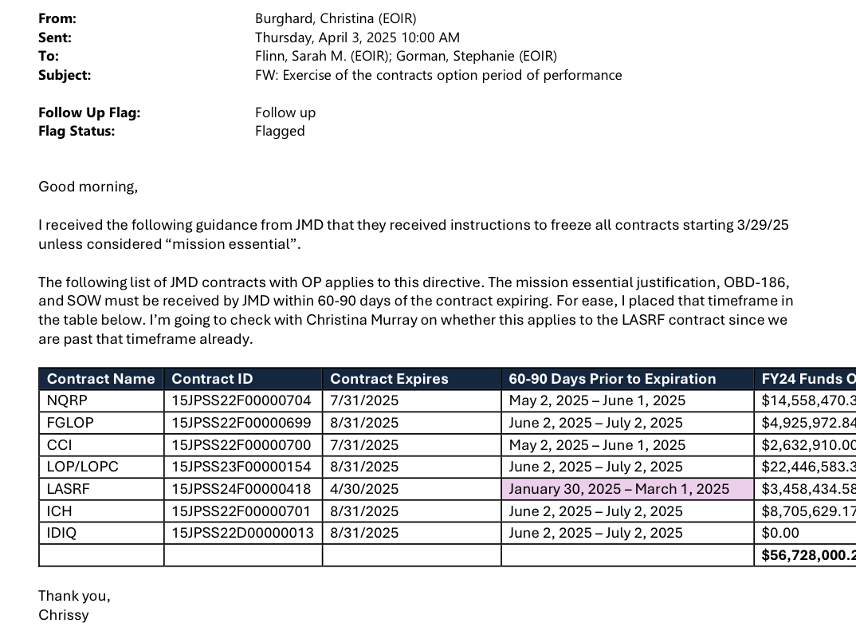

On the morning of April 3, around 9:00 a.m., a contracting officer at the Justice Management Division—the administrative arm of the Justice Department—sent an email to Christina Burghard, a staffer at the Executive Office of Immigration Review, which administers the Acacia Center’s programs. Citing one of Trump’s DOGE executive orders, the contracting officer informed Burghard that she had “received instructions to freeze all contracts starting March 29, 2025 and moving forward unless the award is considered ‘mission essential.’” Burghard then forwarded the instructions to colleagues in her division, along with a list of Acacia Center contracts that “[apply] to this directive.”

Later that evening, at 6:06 p.m., a Justice Management Division staffer named Tarak Makecha received an email from an official at the General Services Administration, an external agency.

Subject: “Acacia.”

Makecha, a former Tesla employee, has previously been identified as a DOGE associate by multiple media outlets. He has been linked to DOGE work at the Office of Personnel Management, the State Department, the FBI, and now the Justice Management Division at the Justice Department.

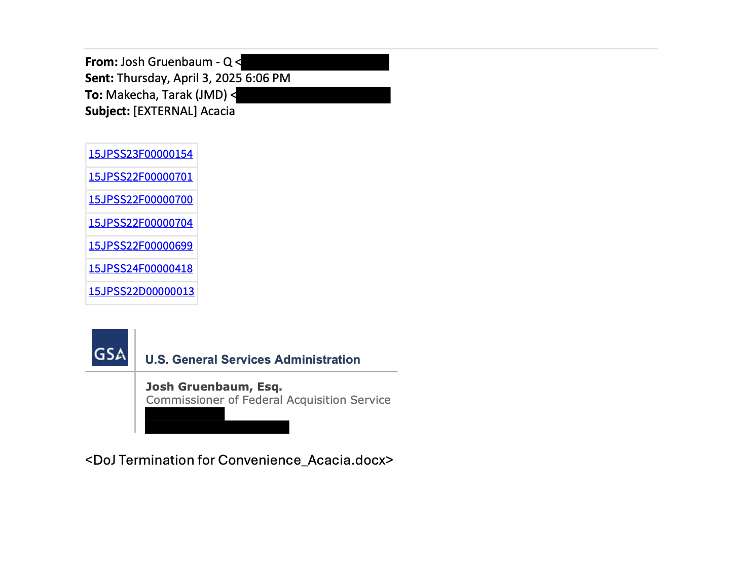

The sender of the “Acacia” email was Josh Gruenbaum, the Commissioner of the Federal Acquisition Service at the General Services Administration. Gruenbaum, like Makecha, has been linked to DOGE. He recently made headlines after he sent a blistering letter to corporate consulting firms that contract with the federal government.

But the email Gruenbaum sent to Makecha on the evening of April 3 contained none of the bluster displayed in his letter to the firms. In fact, it hardly contained anything at all. In the body of the message, he pasted a list of contract ID numbers associated with Acacia Center programs. A document was also attached, titled “<DoJ Termination for Convenience_Acacia.docx>.” The email contained no further explanation or instruction. Makecha, the former Tesla employee turned DOGE affiliate, forwarded the message to several Justice Department officials minutes later. One of the recipients included William N. Taylor, the Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Policy, Management, and Procurement at the Justice Management Division. Taylor is a career official who has been employed at the Justice Department since 1994, according to his biography on the Justice Department’s website.

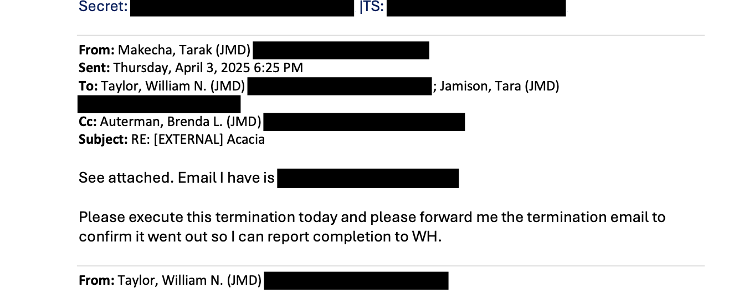

Makecha, the former Tesla employee turned DOGE affiliate, forwarded the message to several Justice Department officials minutes later. One of the recipients included William N. Taylor, the Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Policy, Management, and Procurement at the Justice Management Division. Taylor is a career official who has been employed at the Justice Department since 1994, according to his biography on the Justice Department’s website.

“See attached,” Makecha wrote to Taylor and others at 6:25 p.m. “Please execute this termination today and please forward me the termination email to confirm it went out so I can report completion to WH.”

Makecha did not identify who he would “report completion to” at the White House. Notably, however, Musk is employed as a “senior advisor” at the White House.

Also at the White House is Amy Gleason, the alleged acting administrator of the US DOGE Service. Gleason has previously claimed that she does not supervise DOGE associates who are employed at federal agencies. And though Trump’s DOGE executive order concerning government contracts requires an agency’s “DOGE Team Lead” to provide the administrator with a monthly informational report, it’s not clear if Makecha is the designated “DOGE Team Lead” at the Justice Department. According to The Intercept, he is listed in Justice Department staff records as an “advisor” to the office of the chief information officer, which oversees IT and cybersecurity for the department.

Additionally, nothing in the DOGE executive order empowers a DOGE Team Lead to unilaterally direct the termination of agency contracts.

Makecha’s email also omitted any mention of Judge Moss’s March 17 order, which required the Justice Department to notify the Amica plaintiffs of its intent to terminate at least three business days in advance. But contemporaneous email exchanges between Taylor and other Justice Department officials suggest that Makecha, who is not a lawyer, was aware of the order and nonetheless argued in favor of terminating the contract immediately.

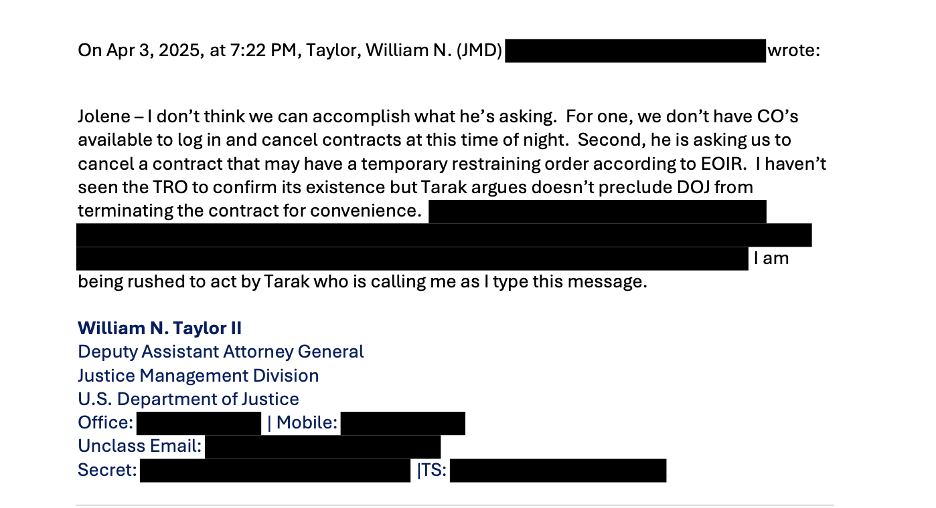

At 7:22 p.m., Taylor wrote to his boss, Jolene Lauria, the Assistant Attorney General for Administration:

Jolene – I don’t think we can accomplish what he’s asking. For one, we don’t have CO’s available to log in and cancel contracts at this time of night. Second, he is asking us to cancel a contract that may have a temporary restraining order according to EOIR. I haven’t seen the TRO to confirm its existence but Tarak argues doesn’t preclude DOJ from terminating the contract for convenience. [REDACTED]. I am being rushed to act by Tarak who is calling me as I type this message.

In its filing, the Justice Department redacted part of Taylor’s email without explanation.

Replying to Taylor minutes later, Lauria—the top official within the Justice Management Division—appeared to question the urgency of Makecha’s directive.

“What is the contract. What is it for. Nothing will happen between tonight and tomorrow in terms of additional spending,” she wrote at 7:25 p.m.

By then, Makecha had already taken matters into his own hands. As Taylor explained in an update to staffers at 7:30 p.m.:

Scratch that. It looks like Tarak got in touch with a PSS CO whom I’ve never met before (Allison Polizzi) and got her to agree to send the termination notice by email and someone can effectuate the termination formally tomorrow. He’s about to email me and loop her in.

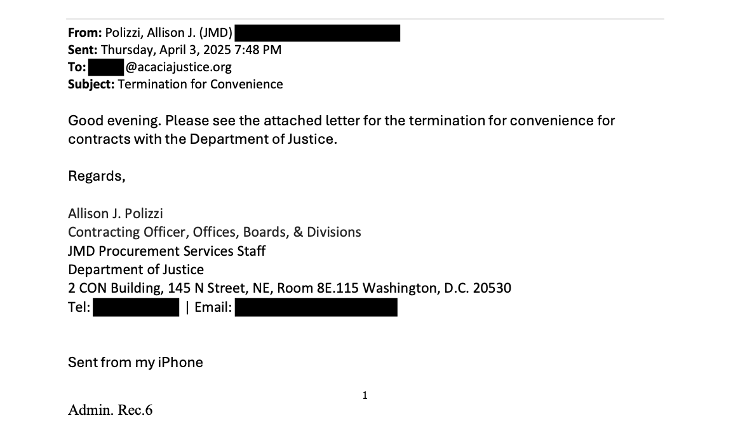

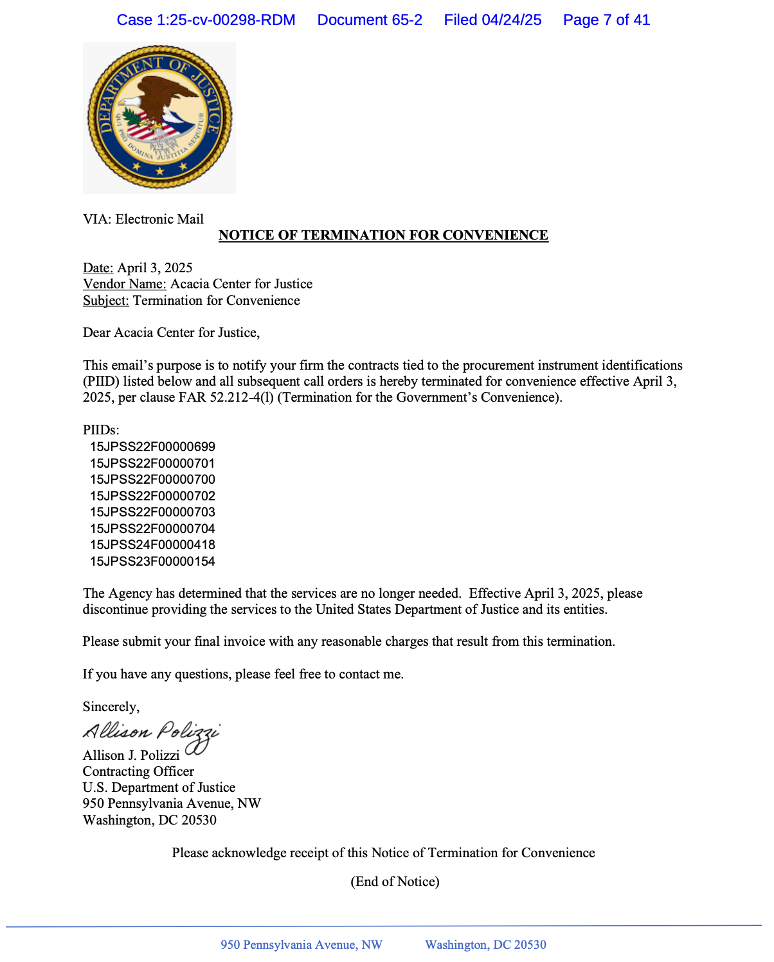

At 7:48 p.m., the contracting officer, Polizzi, sent a termination notice to the Acacia Center—apparently using her iPhone to do so.

The termination letter attached to Polizzi’s email purported to cancel the Acacia Center’s contracts “effective April 3,” stating that its services “are no longer needed.” Bizarrely, though the notice was purportedly sent from a Justice Department officer on departmental letterhead, the meta-data showed that the document was titled “Application for VOA journalist credential,” according to an amended complaint filed by the Amica plaintiffs.

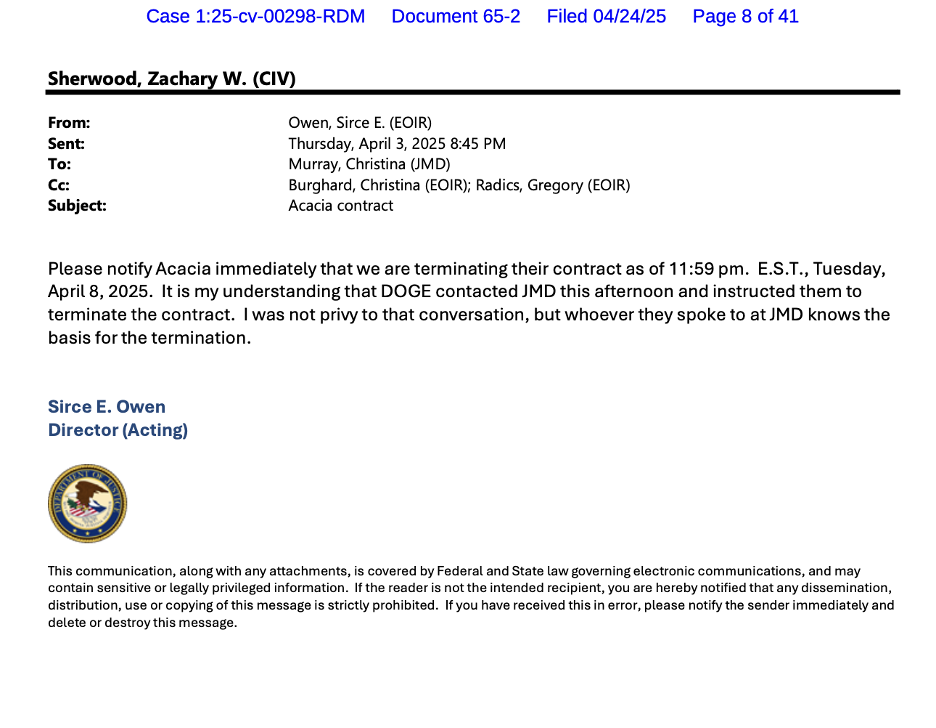

Nearly an hour later, Sirce Owen, the acting director of the Executive Office of Immigration Review, apparently remained unaware of the fact that the contract had been cancelled. In an 8:45 p.m. email sent on April 3, Owen instructed staffers to “notify Acacia immediately that we are terminating their contract as of 11:59 pm. E.S.T., Tuesday, April 8, 2025.”

Owen explained that she was “not privy” to the basis for the termination of the contracts. But as to who directed the termination, she left little doubt: it was DOGE.

“It is my understanding that DOGE contacted [the Justice Management Division] this afternoon and instructed them to terminate the contract,” she wrote.

According to internal emails, Owen wasn’t informed of the contract’s cancellation until the next day, April 4. “Apparently, some form of notification was sent,” a staffer wrote to Owen that afternoon.

The staffer also forwarded the first of several increasingly panicked emails from the Acacia Center’s general counsel, Leah Prestamo, who wrote that she did not know if the April 3 termination letter “was legitimately sent from DOJ or who this sender is.”

“We urgently need to know if this is a real DOJ communication, who our current [contracting officer] is, and whether Acacia needs to be taking action at this time,” Prestamo wrote in another email that afternoon.

In its amended complaint, the plaintiffs allege that the April 3 letter “appeared to be in violation of this Court’s order from March 17 requiring three days’ notice before any termination.”

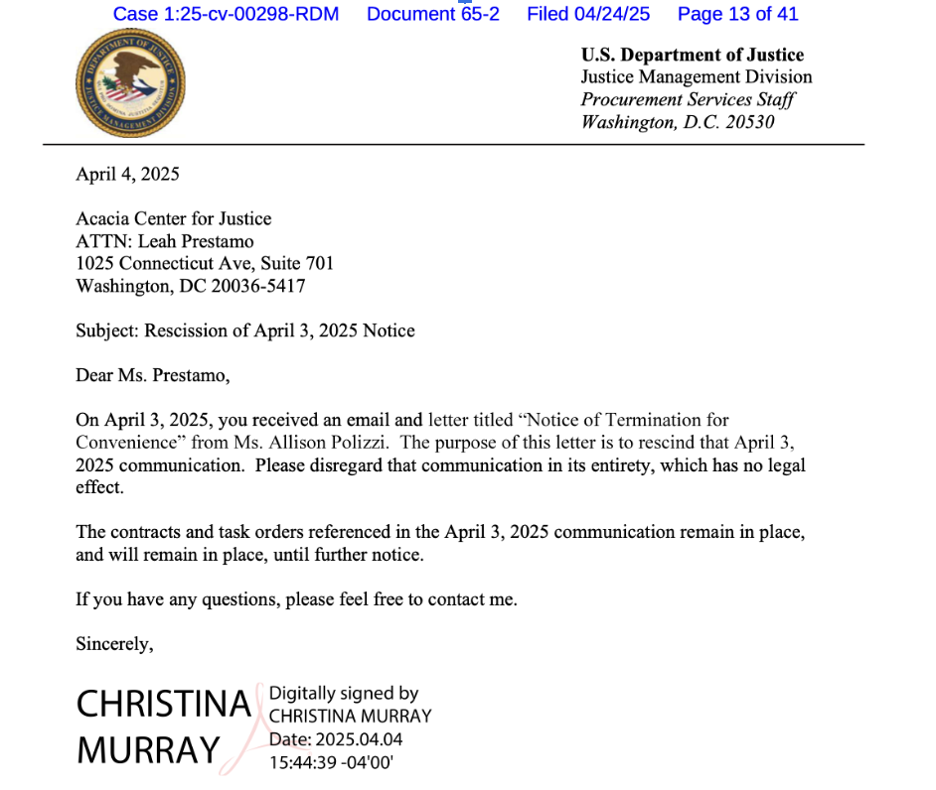

Perhaps that’s why, late in the day on April 4, the Justice Department rescinded the contract termination it sent less than 24 hours earlier. “Please disregard that communication in its entirety, which has no legal effect,” a department official wrote in a letter to the Acacia Center on Friday, April 4.

In a recent court filing, lawyers for the government wrote that the April 3 termination letter “was sent in error.”

Makecha, for his part, appeared undeterred. The following Monday morning, he reached out to Owen and other Justice Department officials. He wrote:

Team,

I understand that the contract termination for Acacia was pulled on Friday. I was briefed that one issue was a three-day lead time required for the termination notice, which is an easy fix.

The more nuanced issue, as I understand it, was an analysis on broader court cases related to Acacia.

Sirce and Greg, I was given you names as the people working through that analysis [sic]. Do you all have a sense on next steps and timing? If you aren’t the right POCs, please direct me to the people that are working on the analysis,

Thanks,

Tarak

Three days later, on April 10, the Justice Department sent the Acacia Center another termination notice. The notice stated that its contracts were being terminated “for the convenience of the government.” It provided no other explanation as to the basis for the termination, which took effect on April 16.

To recap, consider what the government’s own administrative record establishes:

- On the afternoon of April 3, DOGE contacted the Justice Management Division and “instructed them to terminate” the Acacia Center’s contracts.

- Later that evening, a DOGE associate embedded at the Justice Management Division—reportedly as an information technology “advisor”—directed senior Justice Department officials to immediately “terminate” the Acacia Center’s contracts.

- When the senior officials were unable or unwilling to do so within an hour, the DOGE associate took matters into his own hands, soliciting a contract officer to send the termination notice.

- He apparently did so without the knowledge of the Executive Office of Immigration Review, which administers the contracts.

- While the April 3 termination notice was rescinded the following day, a second notice was issued on April 10, again at the urging of the DOGE associate.

The litigation in the Amica case is ongoing, and it remains unclear how the newly-revealed information about DOGE’s role might affect the legal arguments and outcome in the case.

Still, whatever impact it may or may not have within the four corners of the Amica case, the new information reflects an important factual development in the public record concerning DOGE and its activities. The government’s administrative record provides documentary evidence that, at least in some instances, DOGE and its agents are not merely advising but are in fact directing agency action.

I suspect that the Amica case will not be the only case in which the paper trail shows DOGE directing agency decision-making. What’s more, as DOGE-related cases proceed to the discovery phase of litigation, some of the unresolved factual questions surrounding DOGE’s operations and chain-of-command will be answered, either by witness testimony or documents produced by the government.

For now, however, the administrative record in Amica provides the best evidence yet that DOGE is not simply advising—it’s calling the shots.