On Microsoft, the U.S. Government Must Embrace the Stick + Ransomware Disruption

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: This newsletter is part of a collaboration between Lawfare and Risky Business. You can find the full version of the Seriously Risky Business newsletter and previous editions on news.risky.biz.

On Microsoft, the U.S. Government Must Embrace the Stick

Good security happens when the incentives are right. Sometimes that’s because a company is operating under a strict compliance regime, or it has customers that really, really care about security, or it’s in a frequently attacked vertical like banking.

Or it might have suffered an incident that really hurt it and decided cybersecurity threats are existential. That describes Google’s experience. After the Operation Aurora attacks in 2009, Google went about designing and implementing a completely different, secure IT model that still powers the company today.

But what are the incentives guiding Microsoft toward, in the words of public relations weasels the world over, “taking your security very seriously”?

Calling Microsoft in 2024 a monopoly wouldn’t be entirely accurate, but it wouldn’t be entirely inaccurate, either. When it comes to large organizations—corporates and government—Microsoft has the market buttoned up due to a few key strengths.

Its productivity suite, for one, is peerless. There are simply no viable alternatives to something like Excel, for a lot of organizations at least. And of course if you want to use Microsoft’s productivity suite, you’re going to be using the cloud-enabled 365 versions. And because you’re using the cloud versions, that means you’re automatically an Azure customer. So I guess that means you’re going to be an Entra ID customer as well. And seeing as you’re buying all these services, doesn’t it make sense to bundle into a licensing tier and just be a top to bottom Microsoft shop? Throw in some Defender!

When Microsoft is the only company offering such a well-rounded package, there aren’t many incentives in this scenario for Microsoft to really improve the security of its products or underlying services. People just gotta have that Excel.

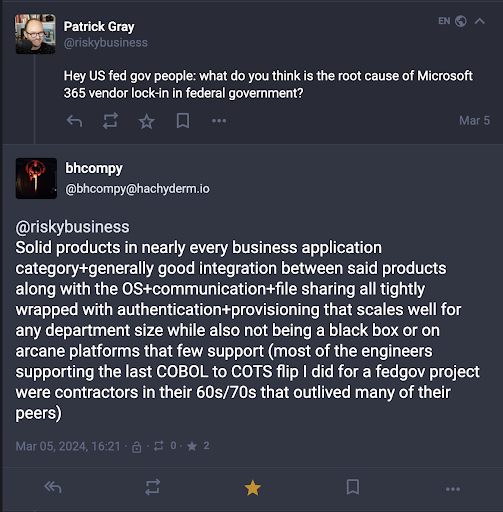

Or, put differently by this Mastodon user, Microsoft dominates because:

Thus, Microsoft doesn’t have an incentive to improve its security because its customers are essentially trapped by them being the only game in town. Unhappy with Microsoft 365? Fine. But where are you going to go?

In November 2023, I was asked to speak to a group of postgraduate students at the Alperovitch Institute at Johns Hopkins University. The conversation naturally turned to the recent string of incidents stemming from Microsoft’s lousy product and operational security. Then came a question: What can we do about all this?

I didn’t have a good answer. Microsoft has succeeded in putting together the must-have suite of business computing tools for the modern enterprise, and the best any government can do to try to get Microsoft to improve things is to lobby it—to treat it almost like another state. Changing its behavior will require diplomacy of sorts. But policymakers must remember that diplomacy is a game of carrots and sticks.

Microsoft is probably about to be whacked by one, too. The U.S. government’s Cyber Safety Review Board (CSRB) is currently working on its report on the State Department email hack. At Risky Biz HQ, we think it is stone-cold insane that Microsoft was not rotating the key material that it used to sign authentication tokens, and if the review board concludes otherwise we will be surprised. In fact, if the CSRB report is anything less than eviscerating, it will be a massive win for Microsoft and a huge blow to the board’s credibility.

But even if the CSRB tears strips off Microsoft, what then? A week in the tech-press news cycle and then no action? That’s the pessimist’s view.

Then there’s the optimist’s view: that a watershed moment is coming. That perhaps the answer to the Microsoft incentives problem could begin to unfurl from the report’s findings. Will the Securities and Exchange Commission find a way to launch an enforcement action based on the CSRB’s work? Would it even have grounds to? Is there room for competition regulators to demand application portability (Excel on AWS! Cats eating dogs! Hamburgers eating people!!!) across different cloud providers? What else can be done to improve competition? Spending caps?

Ultimately it’s time we all recognized that waving the carrot of diplomacy in Microsoft’s direction probably won’t do much to improve things. We don’t yet know which stick will get it done, either, but it’s time for regulators to pick a few and start swinging them. Hard.

What We’re Getting Wrong on Ransomware Disruption

We were thrilled here in the Risky Biz cyberbunker when Western authorities started “disrupting” ransomware crews, but they’re doing it wrong and it’s starting to really grind our gears.

When we started advocating for this type of action back in 2018(ish), we wanted the intelligence community to lead the way. These days, most intelligence agencies worth their salt at least have a cyber division, and those divisions are staffed by properly nasty hackers with twisted little nerd-minds—people who know how to make life unpleasant for their targets using nothing more than an internet connection, their imaginations, and a couple of exotic authorities.

It was not to be.

Policymakers decided that because ransomware is a crime and not an “according to Hoyle,” bona fide national security threat, this is a risk best addressed by a law enforcement-led response, in conjunction with new financial regulations. The law enforcement agencies can disrupt while the regulators can make laundering bitcoin harder.

In typical style, the ransomware problem has been approached by senior government policymakers as one that necessitates a multipronged, whole-of-government response. But the response just doesn’t appear to be designed correctly.

I attended a Counter Ransomware Initiative function at the Australian Embassy in Washington, D.C., last November. The room was full of well-intentioned, intelligent and hardworking bureaucrats nibbling canapes and drinking wine. Australia’s ambassador to the United States, former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, spoke about the importance of the work. He made fun of the Kiwis. It was a good time.

And while these types of multilateral fora are vital to addressing cryptocurrency-enabled crime at scale, as I looked around the room I couldn’t help wonder if the way to really deal with this problem would be found in a different venue ... perhaps at a capture-the-flag hacking contest being held in a dimly lit casino ballroom in Las Vegas.

The issue here is that—as far as we know, admittedly—law enforcement and regulatory actions against ransomware crews have targeted the attackers’ infrastructure and money laundering paths instead of the attackers themselves. The FBI and the U.K.’s National Crime Agency, for example, have done a tremendous job of gaining access to things like the Tor hidden services that underpin attacker infrastructure, collecting evidence from them, and then shutting them down. But the missing piece has always been about the attackers themselves. What is the FBI doing to delete them?

Obviously at the root of this problem is the fact that these criminals are based in Russia and can’t be extradited to the West to face justice. But herein lies the opportunity! It doesn’t take a whole lot of imagination to think of ways to get a Russian in trouble if you have access to their computer.

So here is the official Risky Business list of ways to get a Russian ransomware operator in trouble at home:

- Join their Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) programs as an affiliate and target Russian enterprises. (I like this one. You don’t even need to pull the trigger on encryption; just gain access, and make a bit of noise.)

- Post pro-Ukrainian statements to their infrastructure and social media using their accounts and identities.

- Steal data from Russian government agencies and leak it via RaaS infrastructure.

- Send bomb threats to the Kremlin from their email address.

- Do some straight-up online fraud from their computers, targeting Commonwealth of Independent States countries.

- Find a way to steal their bitcoin, and if you can’t do that, then brick their hardware wallets if possible (lol).

- If access to the correct systems is possible, add them to military mobilization lists.

- Pass lists of ransomware actors’ personal details (including addresses) and net worths to Russian organized (or disorganized) criminals and corrupt officials.

The problem, of course, is that a lot of these ideas are almost certainly illegal. But they’re also great examples of the type of approach that is most likely to make a dent on this issue. And these types of operations are probably better carried out by foreign intelligence community agencies like the CIA, not the FBI.

But then we’re back to the same old question: Is ransomware a bona fide, certified national security threat deserving of that type of response? We think it is, but others disagree.

Further infrastructure deletion attacks of the type the FBI has been engaging in will frustrate the attackers and should continue. But making life hell for the top 50 people who sit at the apex of the ransomware industrial complex would almost certainly deliver better results.

So go on, govvies. Put on those thinking caps and have a chat with your lawyers. Maybe—just maybe—there’s a better way to skin this particular cat.

Three Reasons to Be Cheerful This Week:

- LockBit member sent to prison: A Canadian judge has sentenced a member of the LockBit ransomware group to four years in prison. Russian-Canadian Mikhail Vasiliev was arrested in November 2022 for LockBit attacks as far back as 2020. Vasiliev pleaded guilty in February this year. He also consented to his extradition to the U.S., where he faces charges for LockBit attacks.

- Vendors have to make, keep promises: The Biden administration has approved a vendor security attestation form for software companies that want government contracts. Failure to submit the form will result in non-purchase, and lying on the form will land vendors in deep doo-doo.

- Mike was proved wrong: Pillow magnate (wtf) and all-around loose unit Mike Lindell must cough up $5 million to a man who took up Lindell’s “Prove Mike Wrong” challenge. Lindell offered the sum to anyone who could disprove his claim that Chinese hackers had conducted voter fraud in the 2020 U.S. presidential election. This verdict is extremely funny.

Shorts

The SOHO Routers Are Revolting

Orange Cyberdefense and Sekoia.io have a terrific report out about the networks of compromised residential network devices that attackers are using to obfuscate their origin IP addresses. The report looks at the entire ecosystem of the so-called residential proxy service providers, or RESIPs. And that’s what’s interesting here—it is its own ecosystem and industry. Well worth a look.

Always a Bridesmaid

The Russian government has added a whole slew of new people to its naughty list, including some cybersecurity reporters. Joseph Menn, Joseph Marks, and Tim Starks all made the cut. Sadly, nobody at Risky Business HQ made the list, but there’s always next year.

Risky Biz Talks

In the latest Between Two Nerds, Tom Uren and The Grugq look at Russia’s recent leak of an intercepted German military discussion. From an intelligence point of view, the content of the discussion is only moderately interesting, but Russia decided to leak it in an attempt to influence European attitudes toward providing military aid to Ukraine.

From Risky Biz News:

U.S. cybersecurity budget: The Biden administration has requested $13 billion to fund cybersecurity programs across multiple U.S. federal agencies. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) is set to receive $3 billion under a budget proposal for the 2025 fiscal year. The budget proposal includes $394 million for CISA’s Joint Collaborative Environment, a program that allows private-sector entities to work on joint CISA projects. It also allocates $116 million for new CISA staff and technology to support the agency’s new cyber incident reporting program (CIRCIA). The White House’s budget proposal is unlikely to pass Congress, but experts say it proves the administration’s dedication to improving cybersecurity across the U.S. [Additional coverage in FederalNewsNetwork and CyberScoop]

Microsoft suspends more services in Russia: Microsoft has suspended additional cloud services in Russia following the latest round of EU sanctions. The company suspended access to its business intelligence and CRM products on March 20. The suspension impacts Microsoft PowerBI and Dynamics 365 platforms. Russian IT group Softline says Amazon and Google are also preparing similar moves. [Additional coverage in RBC]

Twitter loses brand safety seal: After an influx of malicious ads redirecting users to crypto-scams for months and months, Twitter has lost its Brand Safety certification from the TAG ad-tech industry group.

Russia’s presidential election: Rostelecom CEO Mikhail Oseevsky claimed that Ukraine’s military intelligence service GUR tried to destroy Russia’s electronic voting system. GUR called the statement propaganda and proceeded to mock Oseevsky on its Telegram channel.

Quantum computer threats: Google estimates that quantum computers will become a threat to cryptographic protocols within the next 10 to 15 years. The company expects to see significant improvements in the quantum computing field by 2030. Google urges the adoption of post-quantum cryptography (PQC) to safeguard against store-now-decrypt-later scenarios.

Apple AirTag class-action: Apple lost a bid to dismiss a lawsuit and will now have to face a class-action case over faulty and negligent design of its AirTag product, which plaintiffs claim has enabled stalkers to track unsuspecting victims. [Additional coverage in AppleInsider]