Organized Labor Is Key to Governing Big Tech

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

In August, then-Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump posted that Vice President Kamala Harris had shared a fake photo from one of her campaign rallies featuring an AI-generated crowd. Even as reporters and attendees readily verified the existence of the 15,000-person crowd, Trump continued to cast doubt in the days that followed. But with few safeguards on Big Tech’s use and development of generative AI (genAI), often there is no easy way to tell what’s real and what’s fake.

In 2018, law professors Danielle Citron and Robert Chesney warned of the “liar’s dividend,” the phenomenon that results when the spread of deepfakes and similar reality-mimicking technologies make the public equally as skeptical of real information as they are of fake. But six years later, Big Tech has forged ahead, racing to put out genAI tools that have exacerbated the problem. Even as democracy hangs in the balance, without guardrails, Silicon Valley has little incentive to change.

For decades now, the law has largely reacted to new tech, sometimes long after that tech has harmfully impacted everything from the individual social media user (consider how social media has affected youth eating disorders) to the national grip on democracy (think of how targeted advertising has enabled political campaigns to craft messaging for hypertailored audiences). With each new technology that comes out of Silicon Valley, it becomes clearer that reactively legislating and litigating is an insufficient approach to regulating an industry that—without safeguards—presents threats to democracy and public welfare.

The U.S. needs a proactive route, and OpenAI has inadvertently shown us the way. Last November, amid the cacophony of headline-grabbing “look what AI has done now” incidents, a different sort of AI story hit the news: OpenAI’s Sam Altman was in short order dismissed from his position as CEO, then reinstated—just days after an uproar from OpenAI staff. Of roughly 770 employees, 738 threatened to quit if Altman wasn’t returned to his position. Labor activists, while noting the threat that OpenAI poses to the labor movement, conceded that OpenAI’s staff had achieved one of the most significant collective actions yet in the tech industry.

The power of organized tech workers, it turns out, rivals that of the government when it comes to effecting change in Silicon Valley. From ensuring AI is not used in warfare to pushing regulation requiring transparency of AI-generated content, a thriving Silicon Valley labor movement could help create the guardrails for Big Tech that are desperately needed.

Serving the Public Good Through Collective Bargaining

The first step to deploying tech unions for the public good is convincing tech workers to unionize in the first place—an effort that may seem unnecessary. The median annual wage for computer and information technology occupations is over twice that of all other occupations, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; if a tech worker is dissatisfied with their job, they’ll just get another one at a different company. Shopping around for the right balance of pay, benefits, and culture is actually an option for this cohort, unlike for other workers. All in all, tech workers seem to occupy a rather privileged corner of the labor market already. Surely time is better spent unionizing other struggling sectors.

The reality is much starker, especially at a time when the tech industry is leading the nation in job cuts with nearly 40,000 in the month of August alone. But even if tech workers did have it so much better than other industries, there is still good reason to focus resources on organizing tech as much as any other sector.

Conventional wisdom suggests that the purpose of organized labor is fairly narrow: First you unionize; then you negotiate a collective bargaining agreement (CBA, in union jargon) that lays out the relationship between you and your employer for the next two or three years in terms of wages, hours, and working conditions (the so-called mandatory subjects of bargaining, rooted in Section 8(d) of the National Labor Relations Act, or NLRA); and then you carry on with your lives. But organizing does not happen in a vacuum: The terms that make up the CBA between employers and employees often inform the CBAs of countless other unions down the line. And, frequently, important terms will set a new precedent—until even the workers without unions or CBAs are enjoying a 40-hour work week, a two-day weekend, employer contributions to health insurance premiums, paid parental leave, and more. Sometimes, these terms even become law: Unions helped pass workers’ compensation laws, the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OSHA), the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA), and of course, the NLRA.

Indeed, the benefits of collective action extend beyond the workers themselves. While traditionally we think of unions as endeavors to improve wages, hours, and working conditions, increasingly organized labor is using its power to help society. A movement called Bargaining for the Common Good encourages unions, community groups, and racial justice organizations to work together to drive change beyond the workplace. Unions affiliated with the Bargaining for the Common Good network have proposed and—in some cases—successfully negotiated provisions in their CBAs concerning racial justice, climate justice, immigration, economic inequality, housing, and more.

Organized tech workers can be a powerful force for social good if empowered to advocate on the public’s behalf. Tech unions’ power can extend beyond the confines of the workplace and the collective bargaining agreement and effect much-needed digital social change in an era rife with misinformation and political upheaval. In fact, unionized workers at Big Tech companies may have the best shot at shaping the directions these companies take for the social and technological good.

Unions outside of the tech industry have already succeeded in establishing best practices with AI in other industries. Last year, after a historic months-long strike, the Writers Guild of America voted to approve a new MBA (minimum basic agreement, the entertainment-industry equivalent of the CBA) that included unprecedented terms governing the use of genAI by both employers and employees in written works. The agreement addressed writers’ concerns that employers may try to usurp their jobs with genAI or otherwise undervalue work created with genAI’s help, laying out terms to prevent either of these fates. It also took up the issue of copyright infringement in the development of genAI, reserving for the guild the right to assert that the use of writers’ works to train genAI systems is copyright infringement. Lawmakers, meanwhile, have largely left the regulation of genAI in creative industries untouched; the U.S. Copyright Office released the first part of a multipart report on genAI and copyright in July of this year, roughly 9 months after the WGA already settled terms on the issue.

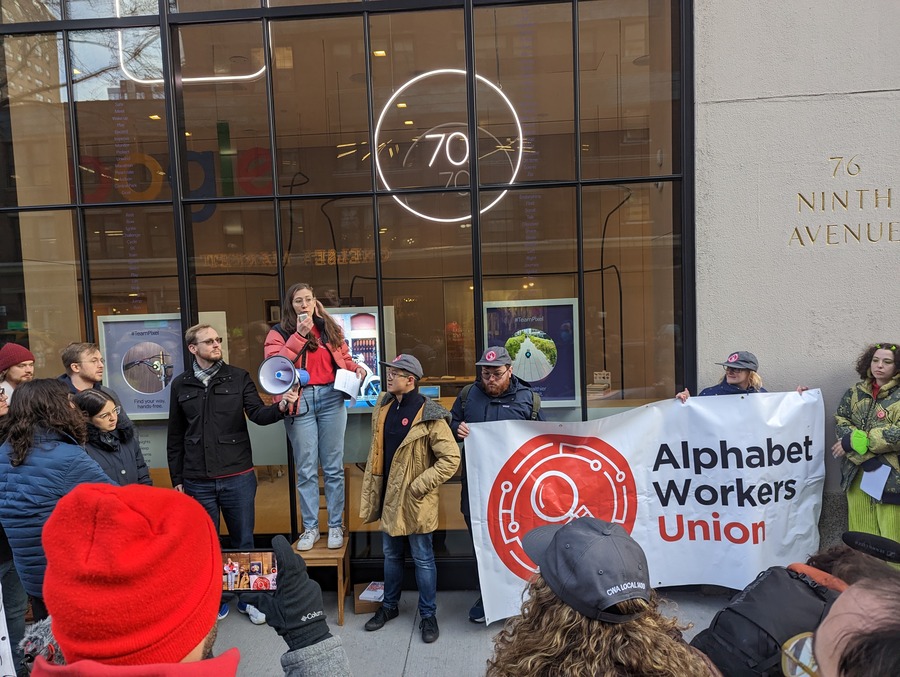

Within the tech ecosystem, we have already seen what organized tech workers can do. Sam Altman and OpenAI aside, workers at Google parent company Alphabet have organized several times to influence their employer’s large-scale business decisions. Before unionizing as the Alphabet Workers Union (AWU) in 2021, workers at Google organized on several occasions to influence the company’s decision-making on ethical grounds, most notably in 2018 when they successfully petitioned the company not to renew a contract with the Department of Defense that would have forced workers to develop AI for use in warfare. Now organized with more than 1,400 members, AWU seeks more than pay raises and better benefits. A banner on the union’s website notes that “Google’s motto used to be ‘Don’t Be Evil,’” and AWU is “working to make sure they live up to that and more.”

AWU’s mission statement focuses on holding Alphabet accountable to its workforce not only in providing a safe and egalitarian workplace for all but also in respecting its workers’ human rights values and concerns as Alphabet navigates its role in a digital world. AWU workers are seeking a seat at the table not just when the discussion surrounds their own salaries and working conditions but also when it considers what projects Alphabet will take on, what governments Alphabet will work with, what products Alphabet will produce, and more.

Regulating Big Tech Through Big Tech Unions

In the age of deepfakes, generative AI, and large-scale data breaches and privacy violations, we need this kind of political power more than ever. While genAI offers exciting new tools for augmenting human work and creativity, its ability to mimic reality poses yet another threat to truth in American democracy. Recall the “liar’s dividend” and Trump’s fluid relationship with genAI, crowd sizes, and the truth. We also saw this play out with the fake Biden robocall incident during the New Hampshire primaries earlier this year, in which AI was used to impersonate Biden and discourage Democrats from voting.

While the EU has made swift strides to confront such political misinformation in the genAI age with its Regulation on the Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising and its AI Act, the U.S. lacks such guardrails. In America, unlike the EU, there is no requirement that users be informed when content they encounter online is a political advertisement or when AI has been used for targeted advertising. Nor are American users protected from AI systems that use “subliminal techniques,” such as deepfakes or personalized advertising, to deceive them or to manipulate their behavior and decision-making—explicitly prohibited under the AI Act Article 5(1)(a). Without these guardrails, and with figures like Trump increasingly treating truth as relative, it hardly seemed a stretch to conclude that Big Tech’s unchecked development could leave American democracy vulnerable this election.

AWU and other tech worker unions could be the check on Big Tech’s AI avalanche that American lawmakers and regulators have struggled to create. In addition to influencing Big Tech to make changes like those outlined in the regulation on political advertising and the AI Act from the inside, tech workers can go a step further by influencing the technology itself. One approach to curtailing AI-driven misinformation is to add “watermarks” to the metadata of all AI-generated content so that users who encounter that content online will know off the bat that it’s not real or human-made. Metadata watermarks would have made it clear from the start that those “Swifties for Trump” images were AI generated; on the flip side, the lack of a metadata watermark on the photo of the Harris crowds would have proved its authenticity before Trump could even begin to cast doubt. In other words, metadata watermarks can thwart the liar’s dividend phenomenon.

For this approach to be successful, however, companies across Silicon Valley would have to work together to agree on common practices for implementing these watermarks across all genAI platforms. Tech unions are ideally positioned to lead this effort: Communicating and coordinating with workers across companies to establish industry best practices is precisely what unions are designed to do. In fact, it is what unions have excelled at doing for a century—the proof, again, is in OSHA, the FLSA, the FMLA, the NLRA, and beyond. We need the voices of tech workers if we’re going to address these dangers properly, and organized labor excels at getting workers’ voices at the table to effect large-scale change.

This tech is the bread and butter of the tech workers who make it. You’d be hard pressed to find a tech worker in the U.S. who hasn’t heard of the General Data Protection Regulation in some measure; all the major, and many of the minor, players in the industry must navigate the EU’s privacy laws if they want to stay in business. And while us common folk might have a general idea of what genAI is, it takes a techie to explain in even the simplest terms how it works and what threats it poses.

If users want comprehensive federal data privacy law, regulations on genAI, and accountability in Big Tech, then unionized tech workers are key. The NLRA gives workers a unique iota of influence over their employers. And when your employer is a Silicon Valley behemoth like Meta, Alphabet, or X, a little bit of influence can go a long way.

Working Within (and Without) the NLRA

There are challenges to achieving these goals through unionization, of course, but they are surmountable. Under the NLRA, employers have the right to refuse to bargain over most “permissive” subjects of bargaining—that is, topics that do not concern wages, hours, or terms and conditions of employment. Likely, Big Tech will decline attempts to bargain over data privacy, responsible genAI, and other controversial elements of tech as not mandatory subjects of bargaining under NLRA § 8(d). But the phrase “terms and conditions of employment” in that section can do a lot of work. Broadly, the Supreme Court says mandatory subjects of bargaining are those subjects that “settle an aspect of the relationship between the employer and employees” (Allied Chemical & Alkali Workers of America v. Pittsburgh Plate Glass). While the Act does not compel bargaining over decisions at the “core of entrepreneurial control,” as put by the court in Fibreboard v. NLRB in 1964, courts have enforced mandatory bargaining over issues as far afield as relocating jobs (Dubuque, a.k.a. United Food and Commercial Workers v. NLRB), pulling out of a contract with a particular client (First Nat’l Maintenance Corp v. NLRB), and even prices for cafeteria and vending machine food in the workplace (Ford Motor Co. v. NLRB).

So Meta workers, for example, may not be able to demand a complete data privacy revolution for all Facebook users establishing clear prohibitions on Facebook’s ability to mine and sell personal data to third parties; but likely, they can at least demand data privacy for themselves in the workplace. And if the Meta union has data privacy at work, then the Microsoft union will want data privacy at work. And if the Meta union and the Microsoft union have data privacy at work, then the Apple union will want data privacy at work, and so on—until data privacy for workers becomes a standard issue in tech union collective bargaining agreements, in other industry CBAs, in political and legislative discourse, and finally, one day, in data privacy laws.

Even if Big Tech refuses to talk about issues like data privacy and AI best practices at the bargaining table, unions can harness the knowledge (and the CBA terms) of their tech worker members to lobby Congress for change directly. Unions do this all the time, in fact; lobbying for policies that benefit both their members and the public is a key component of the vast portfolio of internal and external advocacy that unions do. A prime example from the tech world is the Communications Workers of America’s (CWA’s) nearly 20-year efforts to promote high-speed internet access for all through its Speed Matters campaign. CWA leaders have repeatedly testified before Congress on the need for widespread high-speed internet access in every home in the U.S., the poorest and most rural included. In February 2021, amid the coronavirus pandemic, then-CWA President Christopher Shelton testified before the House Subcommittee on Communications and Technology asking Congress to pass legislation investing $80 billion in infrastructure for high-speed internet access so that kids wouldn’t have to attend remote schooling from a Wi-Fi connection in a McDonald’s parking lot. In November 2021, Congress passed the Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal (aka the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act), which allocated $65 billion for high-speed internet infrastructure, creating jobs for CWA members and expanding broadband to communities in need.

Besides which, not all tech unions have to follow traditional NLRA rules; it’s high time those rules were updated for the modern workplace anyway. Recognizing this, the Alphabet Workers Union formed explicitly as a nontraditional union that has not sought, and does not intend to seek, official certification as a union under the NLRA. The downside of this is that AWU does not have a legal right to collective bargaining and, thus, will not be negotiating an enforceable CBA with Alphabet. The upside, however, is that AWU is free to organize and bargain on its own terms—beyond the confines of the NLRA and its mandatory and permissive subjects of bargaining—and effect much-needed change not just at Alphabet and Google, but on the internet writ large. AWU, unconstrained by the traditional scope of bargaining, could use its organizing power to influence its employer in ways lawmakers, regulators, and traditional unions cannot.

***

Once the workers have included data privacy and responsible AI in agreements, the seed is planted. CBAs are public documents—anyone can find out what these hypothetical unionized tech workers manage to extract from their employers. Both formal and informal tech unions could use their victories to drive lobbying and policymaking at the national level—just as other unions have done for workers’ comp, OSHA, FLSA, FMLA, and the NLRA before.

Where legislative solutions lag, organized labor can pick up the slack. No one is better positioned than tech workers to understand the challenges that Big Tech poses to democracy. Unions should organize the tech industry and harness that knowledge to drive the change that Americans need and that Congress can’t seem to effect—giving citizens greater control over their digital lives.