In “Paper Hearing,” Experts Debate Digital Contact Tracing and Coronavirus Privacy Concerns

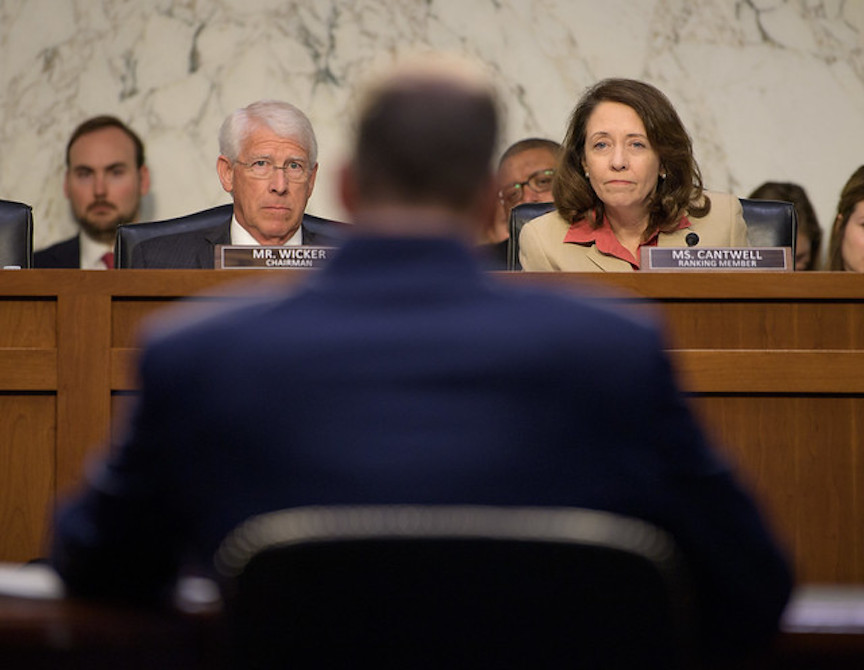

The Senate Commerce Committee recently wrapped up a “paper hearing” on big data and the coronavirus pandemic in which lawmakers and private experts weighed how to balance public health efforts against privacy risks.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On April 17, the Senate Commerce Committee wrapped up one of the body’s first-ever “paper hearings”—a new format adopted in response to the coronavirus crisis, which relied entirely on written questions and answers rather than live testimony. Perhaps appropriately for a hearing conducted in a novel format to prevent the spread of disease, the hearing concerned the role of big data in combating the coronavirus pandemic and the privacy concerns such measures may raise. The hearing featured testimony from private experts who debated the effectiveness of digital contact-tracing efforts and other initiatives using big data to understand the spread of the virus and how to contain it.

The session was carried out entirely through documents sequentially published online. Written testimony, as well as statements from the committee’s chairman and ranking member, were released on April 9, followed by questions from lawmakers. Responses from witnesses were submitted following “a 96-business-hour turnaround time” and made available on the committee’s website on April 17. The session was modeled after a similar “paper hearing” held in late March by the Senate Armed Services Committee to review the posture of the Department of the Army, though this committee’s process differs slightly. The federal government is also considering other measures to conduct business as the coronavirus pandemic has forced Congress into an extended recess. The House is expected to vote this week on changing its rules to allow members to vote remotely by proxy.

The committee heard testimony from private experts on how to use big data in the fight against the coronavirus. The witnesses included Ryan Calo, law professor at the University of Washington; Graham Dufault, senior director for public policy at ACT | The App Association; Leigh Freund, CEO of Network Advertising Initiative; Stacey Gray, senior counsel at the Future of Privacy Forum; Dave Grimaldi, executive vice president for public policy at the Interactive Advertising Bureau; Michelle Richardson, director of the Data and Privacy Project at the Center for Democracy and Technology; and Inder Singh, CEO and founder at Kinsa Smart Thermometers.

The hearing came as tech companies and the federal government have partnered to respond to the coronavirus pandemic, raising concerns about data privacy. Google, mobile advertising companies and even Kinsa—a manufacturer of internet-connected thermometers—have used the data they collect to track patterns like the spread of the coronavirus and compliance with social distancing measures. Google and Apple recently agreed to partner in developing an interoperable Bluetooth-based contact-tracing platform that will be built into operating systems on iPhones and Android phones.

The hearing also follows the collapse in mid-March of negotiations between Democrats and Republicans on the Commerce Committee over new federal privacy legislation. Talks have been sidelined for the foreseeable future as lawmakers grapple with the coronavirus, leaving the U.S. without a comprehensive privacy law—alarming privacy advocates and increasing compliance costs for companies navigating a patchwork of state regulations.

There was broad agreement among the hearing’s witnesses that some uses of aggregated data would help public health officials without impacting privacy. Many stated that collecting location data in an anonymous way would allow government agencies to track the spread of the coronavirus without posing a risk to digital privacy. “Aggregated location data, when it does not reveal device-level information about individual behavior, can almost certainly be used safely and effectively to support public health officials,” said Stacey Gray, senior counsel at the Future of Privacy Forum. She also told lawmakers that “data originally collected from individuals can be transformed or de-identified to a sufficient level that it only reveals aggregate trends, such as movements of people at a city, county, or state level.” Law professor Ryan Calo likewise praised the use of aggregated and anonymized data, saying: “I applaud the Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Report as shedding light on social distancing compliance across the country and the world.”

Inder Singh—whose smart thermometer company has used its data to develop a map showing coronavirus hotspots—argued that there is no trade-off between personal information protection and providing information that could help fight the coronavirus. “We can have both,” he wrote. He also noted that there is “absolutely no way” to identify an individual based on the population-level health insights his company has made public.

One of the topics of greatest interest to senators was the viability of digital contact tracing. Sen. Marsha Blackburn noted that “[f]oreign countries like South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Israel swiftly mobilized collection of cell phone location data to track the spread of the virus and map out infection hot zones” and asked witnesses if it is “even possible to adopt similar measures while still balancing protections for privacy and civil liberties?”

Witnesses were divided over the benefits and risks of relying on digital contact-tracing apps to safely ease social distancing measures. Graham Dufault of the App Association told lawmakers that “Apple’s and Google’s recently announced partnership to enable Bluetooth contact tracing is an example of a system that anonymizes without sacrificing its usefulness.” And Singh argued that “[c]ontact tracing has been an effective way to get exposed citizens the tests and treatment they need, or encourage self-isolation to stop the spread of COVID-19.” The Future of Privacy Forum indicated that it supports Bluetooth-based decentralized contact tracing—like the Apple and Google partnership or a similar proposal from researchers at MIT—and its senior counsel noted there are “several promising frameworks” for mobile apps that could perform digital tracing.

But Calo argued that “voluntary, self-reported, and self-help approaches to digital contact tracing such as MIT’s are likely to prove ineffective and could perhaps do more harm than good.” Users of the app risk coming into contact with infected individuals who do not use the app, or who use the app but are asymptomatic. He noted that malicious actors could falsely report a coronavirus case—and asked lawmakers to envision a situation in which people “are warned not to go near their local polling place on election day because a brazen political operative has downloaded the app and falsely reported being infected.”

Witnesses raised other practical considerations as well. Gray said that contact tracing relies on the availability of testing, limiting the U.S.’s ability to rely on contact tracing if shortages of tests persist. She also noted that “[t]he over-reliance on apps may cause people to over-trust the app’s ability to keep them safe, which may increase social contact and undo the efforts made to flatten the curve.”

Almost all of the witnesses, though, called for the adoption of federal privacy legislation. Many stressed that the U.S.’s lack of a comprehensive privacy law has created uncertainty surrounding data use related to the pandemic. Gray warned senators that “[t]oday, without a national framework, we observe significant confusion within U.S. companies and health authorities around the legality and ethics of efforts to support public health emergency needs.” She said states might also create conflicting exemptions for when data could be lawfully disclosed for public health purposes.

While privacy advocates stressed the need to develop stringent national guidelines, industry groups argued that the pandemic has revealed the limitations of constrictive privacy requirements. Leigh Freund, the CEO of the Network Advertising Initiative, said it was useful during a public health emergency to analyze the location data from various devices. But if a federal law “contains an outright prohibition on the collection of such data,” she claimed, “then it would not be available for this or other purposes.”

Paper hearings are an unusual format, but the Commerce Committee hearing on big data nonetheless gave the Senate a simple means to become more informed on one of the most pressing issues in responding to the coronavirus pandemic. Yet this hearing may be the last paper hearing conducted by the Senate in the near future. Margaret Taylor and William Ford recently wrote:

Going the paper route does have its downsides. Inevitably, something is lost in the lack of live back-and-forth in the hearing room. Members cannot interrupt a witness to pin down an otherwise non-responsive answer or press for a “real” answer about what a government official thinks.

Perhaps the senators agree. After holding one paper hearing, the Senate Armed Services Committee has postponed all future paper hearings. And Sens. Roy Blunt and Amy Klobuchar, the chairman and ranking member of the Senate Rules Committee, are currently negotiating a potential deal to allow the Senate to hold remote hearings. On April 16, dozens of former congressional members even held a mock remote hearing to test the logistics of a virtual event. After a brief experiment with paper hearings, the Senate seems to be moving toward other models of conducting its business remotely.

-(1).png?sfvrsn=7aa9b087_9)

-final.png?sfvrsn=b70826ae_3)