Presidential Intelligence Briefings: The Process Is Working. But Is Trump Listening?

CIA Director Mike Pompeo recently offered rare insights into President Trump’s briefing habits.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

CIA Director Mike Pompeo recently offered rare insights into President Trump’s briefing habits. While articles on Trump’s reported disinterest in the written intelligence document known as the President’s Daily Brief have raised concerns about a lack of engagement, there is nothing inherently wrong with the process Pompeo described during an appearance at the American Enterprise Institute last month. Indeed, Pompeo’s description suggests that the intelligence community maintains access to the president and provides him with intelligence through the PDB process. It is less clear, however, whether Trump’s alleged prioritization of information from sources such as “Fox & Friends” limits his ability to address the complex and interrelated challenges the U.S. and its partners face around the globe.

The good news starts with the revelation that the president is briefed fairly regularly. While a recent analysis of Trump’s briefing schedule suggests that Pompeo’s description of “near daily” briefings may be a stretch, the president otherwise appears mostly engaged. As a former intelligence analyst, member of the PDB staff and daily intelligence briefer, I am keenly aware of how important it is to have an interested and engaged consumer on the receiving end of such briefings. In my experience, the recipient showing up is more than half the battle because there was nothing worse than playing catch-up on missed sessions within the same briefing. Doing so steals precious time away from other pressing issues. Moreover, presidential briefing articles tend to be best understood in the aggregate; missing even a handful of briefings might deprive the receiver of vital context, or arc, to best comprehend the story.

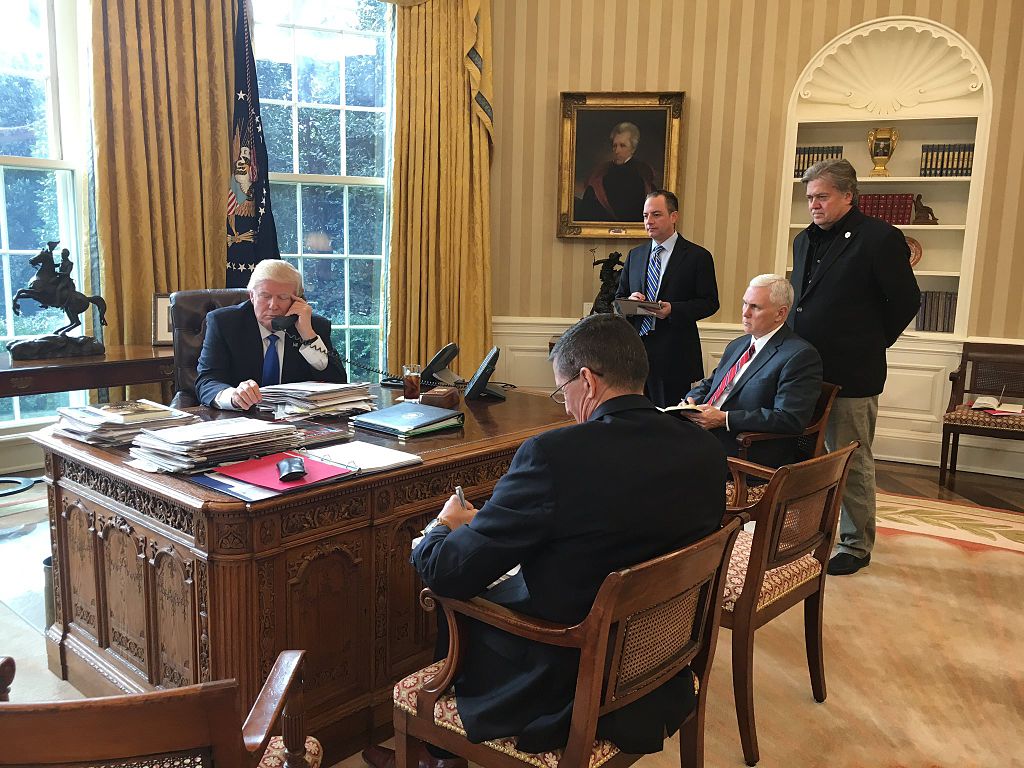

Pompeo said that Trump is usually briefed in the presence of National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster, Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats, a professional briefer, a CIA officer, Vice President Mike Pence (when he is town) and Pompeo himself. The presidential briefing has not historically been a group activity, but this practice can pay significant dividends. For one thing, multiple participants hailing from different walks of life usually means multiple perspectives and avoidance of groupthink. Pompeo noted that at times Trump engages in a “rambunctious back-and-forth” with his national security team over intelligence in the report. This suggests that briefing participants are challenging each other on the intelligence—whether related to assumptions underpinning assessments, the degree to which intelligence analysis comports with their personal views, relevance to the president’s agenda or other factors. That is a healthy phenomenon. At the end of the day, intelligence is meant to produce sound policymaking on priority issues, and that can happen only if it is discussed and evaluated among senior leadership.

These sessions at times result in questions that are sent to the intelligence community for responses. Pompeo noted, for instance, that the president was at one point dissatisfied with the information he was receiving on the dire condition of Yemeni citizens and requested more specifics on the situation. It took several iterations of question and answer with intelligence analysts before he was content. Again, the process is supposed to play out in this way. Intelligence is inherently ambiguous, and asking follow-up questions indicates that the president and his team are not simply glossing over details or overlooking gaps in knowledge. Instead, the president is tasking the briefer to dig deeper and determine whether the information exists somewhere within the intelligence community or if new collection and analysis are required.

Pompeo also mentioned that the briefing is divided into “three buckets”: timely pieces that pertain to daily events, upcoming events over days or weeks, and “knowledge-building” items. Knowledge-building refers to strategic topics that the president should be considering in the background as he makes decisions on world affairs. It is always a good idea to arrange the book this way, and, given that the organization of this intelligence report is a presidential prerogative, here too the process suggests reasons to feel encouraged. Trump and his staff clearly believe the administration should be thinking strategically.

The intelligence community has apparently adapted to Trump’s briefing style. As I have written previously, the presidential briefing is a two-way street, meaning the intelligence community must find smart ways to “tee up” pieces to rise above the noise and compete with the many other sources of information vying for the president’s attention. The intelligence itself cannot be changed, of course, but the packaging can, and briefings are often altered to meet the president’s preferences. Pompeo was quoted last year as saying that Trump enjoys “killer graphics,” and the president himself has emphasized brevity for intelligence briefings. During the transition he said, “I like bullets or I like as little as possible.” I have been told anecdotally that the intelligence community has obliged these requests, with PDB articles now typically only half a page in length. In my experience, even with shortened articles, the intelligence community retains most nuance and substance through rigorous editing and review.

That is the good news about the process. The more worrisome news came out after Pompeo’s comments at AEI: According to the Washington Post, Trump prefers oral briefings to written documents and “rarely if ever reads” the written report. This reporting was subsequently disputed by the director of national intelligence, Coats, who said the suggestion that Trump does not read the briefing materials “is pure fiction.”

Suggestions that Trump is not reading most or any briefing materials has led some to worry that he might be missing important nuance and strategic context. For example, according to the Post report, former CIA director and defense secretary Leon Panetta said that “something will be missed.” But this is not necessarily the case. Each person has a different learning style, which makes it difficult to judge the particular merits of verbal vs. written consumption of intelligence. And there is nothing inherently wrong with the process Pompeo depicted. During his talk at AEI, Pompeo disclosed a rare public example of how the president used timely intelligence to shape his thinking on policy: Trump was curious about the funding of Venezuelan security forces and ultimately used the intelligence gleaned from the daily briefing to enact sanctions against Nicolas Maduro’s regime. This is precisely the purpose of the intelligence briefing.

There are reasonable critiques to be made of the story Pompeo told. Many observers in this politically-charged environment may discount or minimize Pompeo’s observations of Trump’s intelligence-consumption habits. They can argue that Pompeo is a Trump loyalist who would never publicly describe his boss in a negative light. And Pompeo’s comment that Trump can absorb intelligence on par with that of a “25-year intelligence veteran”—when he has no prior intelligence or government experience—might be an example of overstatement. Moreover, tensions exist between the administration and the intelligence community over the Russia investigation, particularly between the president and the FBI. And of course, media reports that Trump prioritizes information from “Fox & Friends” or other television and online sources seem to diminish Pompeo’s account that the president takes his intelligence briefing seriously. Any president should trust that analysis from his intelligence community is produced by experts and, as such, is rigorously vetted and undergirded by multiple, credible sources. This may not always be true with media reporting.

It is impossible for outsiders to fully evaluate what goes on inside the Oval Office. But even if details of Pompeo’s account are questionable, there are reasons to think the presidential intelligence briefing is working well. At a minimum, the president is briefed on a fairly regular basis and, regardless of how the information is presented, he appears engaged in discussions with senior staff and the intelligence community about content. Ideally, this process is informing his national security decision making over less authoritative and distracting sources of information, but unfortunately this may not be the case.