The Privacy Act Project: Revisiting and Revising the Privacy Act of 1974

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

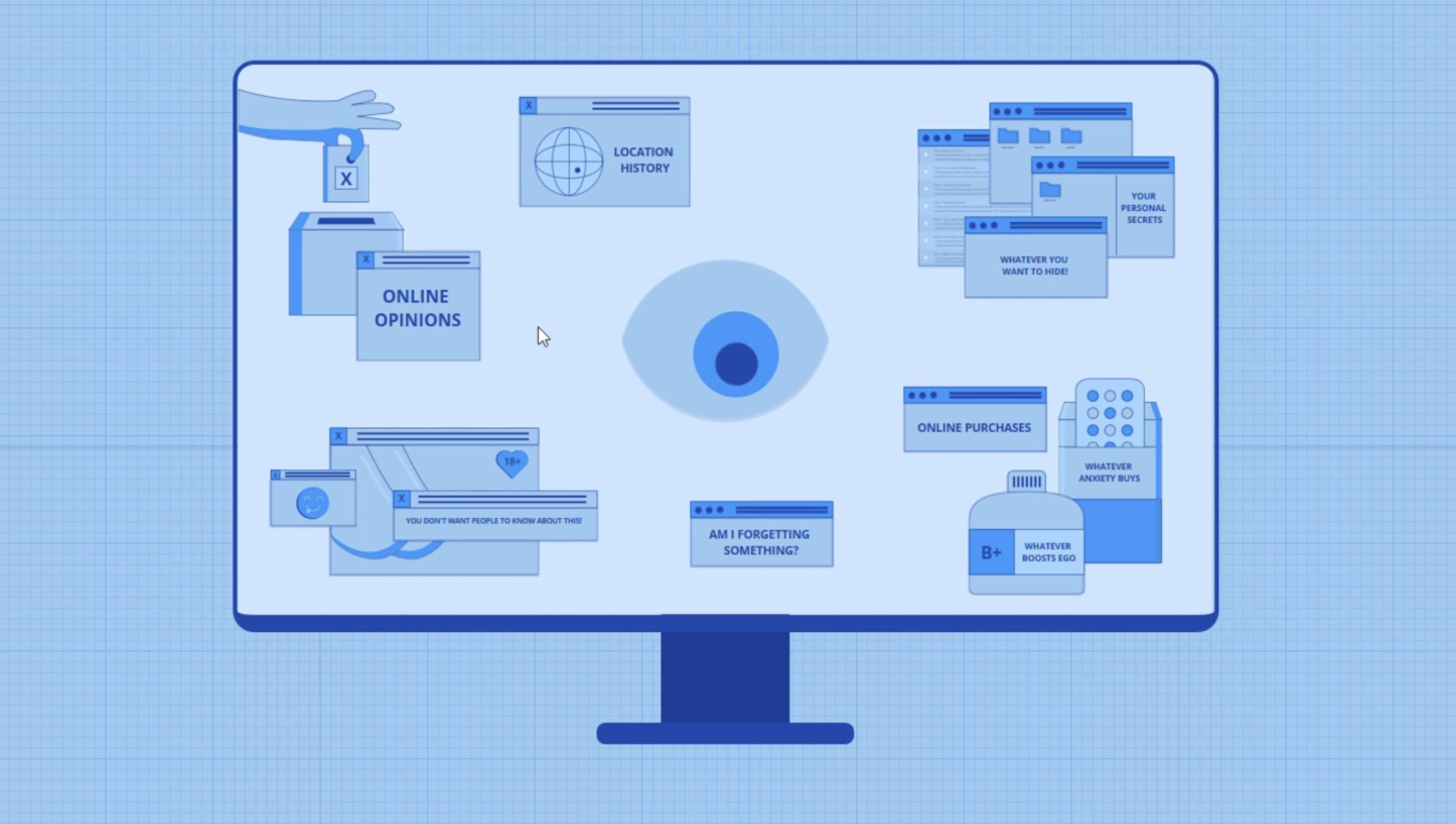

The Privacy Act of 1974 is an orphan. At a time when privacy is a hot legislative topic just about everywhere, almost no one has examined the Privacy Act, one of the oldest information privacy laws in the world. The act reflects the technologies of the 1970s, like ancient mainframe computers (that had less computer power than your smartphone) and filing cabinets filled with paper records—it’s that old.

The other feature of the Privacy Act that keeps it off current radar screens is that the act applies to U.S. federal agencies (and some federal contractors). Most contemporary attention to commercial privacy matters pushed privacy debates away from routine federal government record-keeping practices and onto things like social media privacy, targeted advertising, consumer rights.

Nevertheless, federal agencies maintain vast amounts of personal data, and they use that data to make decisions about all of us that affect our lives in major ways. The Privacy Act applies to agencies like the Internal Revenue Service, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Social Security Administration, the Department of Homeland Security, federal law enforcement agencies and more. The American public deserves better privacy protections from the government than a nearly 50-year-old law provides.

The World Privacy Forum just published a comprehensive report focusing on the Privacy Act, including its successes and its failures as a matter of law and policy. The report does not focus on actual implementation by agencies, something that has been inconsistent over the years. The report instead includes a proposed revised law that brings federal agency privacy policy and controls up to date. The proposed bill is titled the United States Agency Fair Information Practice Act (USA FIPS Act). The draft, together with a history of the Privacy Act, a discussion of core policy issues, and a section-by-section analysis of the proposed law can be read here.

The broad goals of the proposed bill are to:

- Bring the Privacy Act of 1974 up to date in recognition of current approaches to privacy protection, modern personal information processing activities and newer information technologies.

- Preserve individual rights in existing law and make it easier for individuals to exercise those rights.

- Allow agencies to implement their responsibilities in a more efficient and effective way while providing better tools for individuals and public interest groups to hold agencies accountable.

- Make the new act consistent with other relevant information management laws, while bringing most privacy-related obligations for federal agencies under one legislative framework.

Key Areas of the New Law

Both the Privacy Act and its proposed replacement are long and complicated laws. Below, we outline three key areas of the new law that will improve on the shortcomings of current law and practice.

The System of Records Requirement

A core concept of existing law depends on agencies maintaining a “system of records.” Most provisions of the act apply to agency systems. Yet the act can apply differently to two similar collections of personal records depending on the retrieval method for the records. That makes no sense for electronic records, which can typically be retrieved in multiple ways by untrained people at whim, no matter how an agency stores or organizes its records.

Agencies must describe their systems through Federal Register notices. This part of existing law has notable value. It provides a resource with details about federal agency record keeping that exists nowhere else. Even though agency Privacy Act notices are not always up to date or complete, the notices remain useful to anyone trying to understand the basics of agency record keeping practices for personal information. Although the U.S. lags far behind the rest of the world in privacy legislation, the publication requirement of the Privacy Act is unique. Europe abandoned a comparable requirement years ago as too cumbersome.

The USA FIPS Act proposes to replace the law’s existing system of records with a functionally based concept called an “agency activity affecting privacy” (A3P). Agencies have broad authority to decide how to group activities within A3Ps rather than defining record-keeping activities by filing methods. If an agency has three separate data systems supporting a particular program, it can define all three systems as part of the same agency activity. That should improve public understanding.

In the proposal, descriptions of A3Ps must include more information about agency use of nongovernmental records. Agencies use many private-sector databases to carry out government functions. While much of that use is mundane, the intersection between the government and the private sector needs more attention. A description of an A3P must identify data sources including commercial, governmental and other sources that the agency routinely reviews, consults or uses.

Disclosure Authorizations

Existing law allows an agency to define an appropriate disclosure for a system of records by establishing a routine use. The law’s substantive requirement—that a routine use be compatible with the purpose for which a record was collected—is too vague because it relies on the undefined notion of “purpose.” Agencies tend to view routine uses as largely procedural. As long as they publish the right notice in the Federal Register, they can authorize just about any disclosure they want. It can be nearly impossible for anyone to challenge that authorization.

One of the major challenges of a privacy law that applies to more than a hundred federal agencies, each with multiple and highly varied functions, is to write standards that work across so many different organizations with diverse statutory authorities. Privacy standards must allow agencies to function, but they also must erect reasonable barriers to the misuse of personal information. The problem is that standards by themselves cannot accomplish this objective. The failure of the routine use standard is a prime example. It is simply too vague. Further, it seems highly unlikely that any word formula can succeed here. This is a common problem that all broadly applicable privacy laws all around the world face, and none of those laws offers a useful solution. More vague words are not the solution.

The proposed bill offers one response that uses procedures to supplement necessarily broad standards. The USA FIPS Act replaces routine uses by giving agencies the ability to define three flavors of “agency designated disclosures.” The new elements are procedural limits and requirements that are largely absent from the existing law. These procedures include better descriptions of the disclosures and their purposes; identification of the class of recipients; identification of the agency personnel who can authorize disclosures; and approval of the description of the disclosures by the agency’s chief privacy officer (CPO). The objective is to prevent “self-dealing” by program officials who might write broad disclosure authorizations to give themselves unbounded discretion. Other provisions in the proposal include better use of privacy impact assessment processes, more meaningful public notice and comment opportunities, and a new judicial review process.

Remedies

Judicial review under the Privacy Act is mostly a failure. Individuals can pursue their own rights of access and correction more or less effectively under the act. However, Supreme Court rulings limit the ability of an individual to recover damages. Also, many actions by agencies, public interest groups, or others cannot readily challenge core elements such as routine uses, the scope of record systems and procedural obligations. The USA FIPS Act modestly improves remedies for individuals, allows for meaningful class action lawsuits with caps on damages, and creates a new administrative remedy that allows anyone to pursue complaints that an agency is not complying with the law. The first step of this remedy is filing a complaint with the agency CPO. If the CPO cannot resolve the matter to the complainant’s satisfaction, an appeal to federal court is available.

Additional Requirements

In addition to these three major changes, the USA FIPS Act:

- Grants rights to foreign nationals—not just citizens and resident aliens. The act’s failure to grant rights to foreign nationals is unfair, unnecessary and out of step with foreign data protection laws. It is also a small but important step toward harmonizing U.S. privacy laws with the rest of the world.

- Requires each agency to have a chief privacy officer with significant substantive and procedural authority. Some agencies already have CPOs, and some of those CPOs have been effective in overseeing agency activities some of the time. A CPO is not a panacea for all privacy problems. Lawmakers cannot legislate good management, and not all CPOs are or will be good at their jobs. Still, CPOs are useful much more often than not.

- Establishes meaningful requirements for Privacy Impact Assessment processes. The Privacy Impact Assessment requirement in current law lacks any meaningful substance. Many agencies comply with short, “check-the-box” assessments that accomplish nothing.

- Adjusts but largely continues existing exemptions and computer matching obligations. The proposal eliminates some existing exemptions, but the main exemptions for law enforcement and intelligence matters remain a challenging area. Other national privacy laws often struggle with the same problem.

- Extends the scope of the law beyond agency contractors to include federal grantees. Some agencies understand that the law covers contractors who carry out agency functions but not grantees. These agencies sometimes use grant instruments in order to avoid applying the Privacy Act to activities when it is inconvenient for the agency.

- Establishes enhanced criminal penalties. Current penalties are misdemeanors with minor fines. Criminal prosecutions are rare. The proposal adopts the criminal penalties for health records that offer serious consequences for anyone trying to exploit records for a profit.

- Provides agencies with a long transition period to move from compliance with the Privacy Act to compliance with the USA FIPS Act. Moving from the old law to a new one will take a fair amount of time, especially for large agencies like the Department of Defense, the Justice Department and the Department of Homeland Security. The proposal gives a long time for the transition, and it allows agencies to transition by program or function in order to disperse the work required for compliance over time.

Building on What Works in Current Law

While the proposed bill is a complete redraft of current law, it is more evolutionary than revolutionary. It builds on the successful parts of the existing act. The current Privacy Act implements all elements of Fair Information Practices (FIPs), the policies that form the basis for national privacy laws all over the world. The proposal does the same and includes a statement of FIPs. One objective of that statement is to stop agencies from redefining FIPs by leaving out or changing inconvenient elements.

The proposal, as is the case with the current law, applies to all federal agencies and to nearly all federal activities that process personal information. A core principle of current law and the proposed draft is that there are no secret systems of records maintained by federal agencies. The proposal continues that policy. This proposal also seeks to improve the current law’s provisions concerning individuals’ rights of access and correction. Finally, the act usefully limits federal agencies from collecting some personal information without adequate justification. These remain important constraints in the proposed law.

Any legislative proposal requires the balancing of multiple objectives and interests. The proposed USA FIPS Act is no different. It keeps the best features of current law and adjusts the rest. Not everyone will agree with all the choices made in the draft, but we hope there is broad agreement that it is time to revisit and revise the Privacy Act of 1974.