Progress on Transatlantic Data Transfers? The Picture After the US-EU Summit

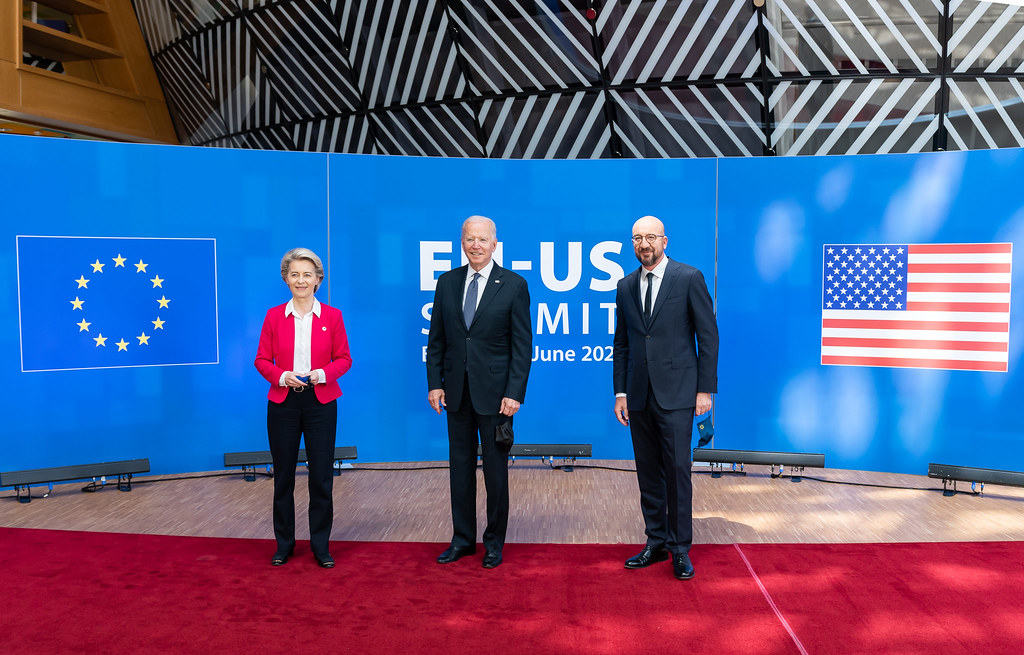

President Biden’s June 15 summit meeting in Brussels with EU leadership put cooperation on technology and trade at the forefront of the transatlantic relationship, but it did not yield a breakthrough in the ongoing negotiations to restore data transfers from Europe to the United States to a stable and durable footing.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

President Biden’s June 15 summit meeting in Brussels with EU leadership put cooperation on technology and trade at the forefront of the transatlantic relationship, but it did not yield a breakthrough in the ongoing negotiations to restore data transfers from Europe to the United States to a stable and durable footing.

The White House reportedly had been pressing EU counterparts for a specific political commitment at the summit to rapidly conclude the difficult negotiations, which began last year following the invalidation of the US-EU Privacy Shield Framework by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in its Schrems II judgment. That ruling found that U.S. surveillance law offered insufficient judicial protection for Europeans who suspected the U.S. National Security Agency had acquired their personal data, and has put the U.S. government on the spot to develop an improved system of redress. The final wording of the Joint Statement issued at the conclusion of the summit, however, only commits blandly to ensuring cross-border data flows and enhancing privacy protections, and “to continue to work together to strengthen legal certainty.”

U.S. Department of Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, who has responsibility for the negotiations to repair the Privacy Shield, travelled to Brussels with the president and met separately with her senior EU negotiating counterpart, Commissioner for Justice Didier Reynders. They issued a similar statement stressing their “shared commitment to find a comprehensive successor to Privacy Shield that is fully in line with the Schrems II requirements and with US law.”

Later in the week, Reynders expressed the view that a high-level political agreement with the United States could be reached before the end of the year. A similar Brussels perspective on the difficult dynamics of the negotiation emerged in a June 15 tweet from Ralf Sauer, deputy head of international data flows in the Commission’s Directorate-General for Justice, who wrote that “speed should not trump quality” and reminded that a “Schrems III” debacle at the CJEU had to be avoided.

The two sides reportedly remain far apart on how to remedy one of the principal defects in the Privacy Shield identified by the CJEU:a lack of independent oversight and redress in the U.S. system for European persons who suspect they were surveilled by the National Security Agency (NSA). The EU evidently believes that only a non-executive U.S. agency such as the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, acting perhaps in combination with the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, offers an independent remedy that would survive the inevitable CJEU challenge to a future agreement. The United States appears to have little interest in considering changes to its surveillance statutes—changing surveillance authorities is a difficult prospect in Congress at any time but especially so when prompted by foreign data protection scruples. Bridging this gap, perhaps through a U.S. executive order pending a permanent legislative solution, is conceivable. But it will take time to build support for such a compromise in both the U.S. national security community and in Europe.

Over the past year, companies that previously had relied on the Privacy Shield as the legal basis for their data transfers from Europe to the United States largely have turned instead to standard contractual clauses (SCCs) for this purpose. SCCs are contractual guarantees of privacy protection between a data exporter and importer, the terms of which have been pre-agreed by EU authorities. In Schrems II, the CJEU validated SCCs for data transfers to the United States if companies put into place supplemental measures protecting against U.S. national security access. However, the SCCs currently in use at the time of the Court’s scrutiny in Schrems II predated the adoption of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and badly needed updating. The CJEU also did not specify the nature of the supplemental measures necessary for SCC-based international data transfers to third countries. After the court ruling, the Commission undertook to update the existing SCCs, while the European Data Protection (EDPB), the coordinating body of member state data protection authorities (DPAs), assumed the latter task.

This month both the Commission and the EDPB completed their work. The Commission acted first, issuing new SCCs on June 4. The new clauses, which are binding EU privacy law, instruct a data importer to assess that country’s surveillance laws and practices. They also impose an obligation on data importers to take into account the nature of the data, the company’s technical and organizational safeguard measures and its own past experience (if any) with national security data requests. Companies, in other words, must do their homework to assess the risk that a foreign government will seek data access, and they also must commit to fight such requests in court if they consider them unlawful. The new SCCs count as good news for companies because their risk-based approach does not definitively close the door to international data transfers in any particular case; rather, it makes the decision contingent on a careful analysis of factors.

The EDPB Recommendations on supplementary measures, issued on June 18, serve as non-binding harmonized guidance from member state privacy regulators responsible for enforcing EU privacy law. The Board, responding to sharp criticism of its draft guidance, largely aligned its final recommendations with the Commission’s approach to assessing the risk of third-country national security data access. It agreed on the importance of looking beyond law on the books in third countries to authorities’ actual data demands and to data importers’ practical experience in responding to them, as part of an overall assessment. The Board specifically left the door open to the possibility that supplementary measures including encryption, pseudonymization and other technical and organizational protections for data would be sufficient to allow transfers to the United States, notwithstanding U.S. law and practice under Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).

On the other hand, the EDPB left largely intact its severe preliminary advice from November 10, 2020 that there are two scenarios in which no safeguard measures can be completely effective to remove the risk of foreign government surveillance. This admonishment means that, in the EDPB’s view, data transfers of these types from the EU utilizing SCCs should not occur at all. Both situations arise where end-to-end encryption of data is technically inconsistent with the desired uses: where the importer is either a cloud services provider that needs access to data in the clear from the exporter, or an entity conducting shared business purposes with the exporter (such as a help desk for customers or a corporate human resources office). The unavailability of SCCs for these types of data transfers to the United States and other third countries remains a potentially significant problem. The Board did, however, open one new potential loophole – the possibility for a company to demonstrate that a foreign surveillance authority does not apply to it “in practice”—although its utility remains to be seen.

While hopes of a quick ‘win’ for transatlantic data transfers at the US-EU summit did not materialize at the summit, some recent progress has been made. The Commission’s new SCCs offer important guidance to companies worldwide, particularly in America, that have been coping with the uncertainty that followed the Schrems II ruling. The EDPB’s definitive recommendations on supplemental measures also provide much-needed clarity in handling the fraught issue of government access to personal data.

Arriving at a successor to the Privacy Shield Framework is still the looming major hurdle to a return to relative stability for transatlantic data transfers. The longer it takes, the more likely it becomes that European data protection authorities in the meantime will take action of their own accord to interrupt data transfers to the United States, and the greater the temptation for EU member state governments to choose local digital service providers not subject to the reach of U.S. surveillance laws. These trends are already evident, and the U.S. government needs to act swiftly and decisively to counteract them.

Biden himself is no stranger to the continuing challenge for the United States of balancing security and privacy interests with the European Union. As Vice-President in 2010, he addressed the European Parliament in a successful effort to achieve its approval of an agreement allowing transfer of banking transaction data to the U.S. Terrorist Finance Tracking Program. Five years later, he spoke with Commission then-President Jean-Claude Juncker as the Privacy Shield Framework was nearing completion. Biden’s presidential trip to Europe as his first foreign destination has built tangible transatlantic goodwill. That will prove important as his administration strains to settle the latest data privacy dispute with Brussels.

.jpeg?sfvrsn=f6228483_10)